Pete Maresca went from being a comics collector and fan to being a publisher and one of the premiere figures working in comics restoration. His company, Sunday Press Books, made a splash with their first book, "Little Nemo in Slumberland," an oversized volume which debuted to high praise from fans. Since then, Maresca has gone on to publish a second volume of "Nemo" Sunday comics as well as a variety of other books, including earlier work by Winsor McCay, "The Complete Color Little Sammy Sneeze: Featuring Complete Hungry Henrietta," "George Herriman's Krazy Kat: A Celebration of Sundays," which Maresca edited with Patrick McDonnell (Mutts) and "Sundays with Walt and Skeezix." Sunday Press has also edited a number of other books offering a look at early Twentieth Century comic strips including "Forgotten Fantasy: Sunday Comics, 1900-1915." Thier latest book, released in late-July, is "Society is Nix: Gleeful Anarchy at the Dawn of the American Comic Strips."

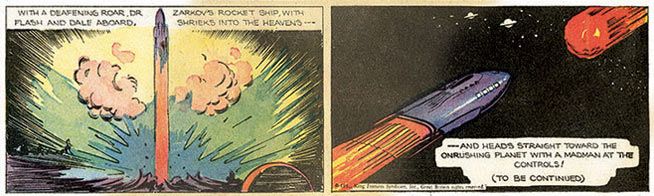

Beyond Sunday Press, Maresca has also overseen the restoration of "Flash Gordon" for Titan Books, three volumes of which have been released thus far. The series will continu, with future volumes picking up Austin Briggs' run on the comic. CBR News spoke with Maresca who was happy to talkabout his career and work while giving us a crash course on the process of restoration.

CBR News: The first time I came across your name was almost a decade ago, when you published the "Little Nemo in Slumberland" book. What led to you to work in comics restoration and become a publisher?

An unrestored page from "Flash Gordon" (top) and Maresca's restored version

Pete Maresca: I consider myself an accidental publisher. I spent 15 years in the high-tech entertainment business and was doing consulting work putting comics on mobile phones. In 2004, I realized the "Little Nemo" centennial was coming up the following year and had noticed my own collection of original tear sheets was becoming more faded and brittle with each decade. McCay's masterpiece needed to be preserved, and cried out to be reproduced in its original size -- but after months of being turned down by major publishers, I realized I had to do it myself.

I did was comfortable with Photoshop and had some experience with digital restoration, but knew nothing about creating a printed book. Thanks to the assistance from publisher and designer friends in Paris, I got myself a quick -- though not painless -- introduction to the process, and Sunday Press was born.

Why is it important to create such large books and to reproduce the art at that size? What do you personally like about it and in what ways do you think the art benefits?

I started collecting Sunday comic sections in 1973 when I discovered treasure trove of thousands of sections dating back to the earliest comics. There were no reprint collections in those days, other than a few small black-and-white fanzines that Xeroxed the pages. So my introduction to McCay, Raymond, Foster, Herriman and the other greats was as they were intended to be read, in full broadsheet size and original colors. The early comic artists drew with such incredible detail that much is lost in the smaller reproductions. Many who see my full-size books say that it's like viewing their favorite comics for the first time, and that kind of compliment makes the effort worthwhile.

What's the latest book to come out from Sunday Press Books?

The book that is necessary for the understanding of comic strips, the origin of the comics of the Sunday supplements. "Society is Nix: Gleeful Anarchy at the Dawn of the American Comic Strips" presents the work of over 50 known and unknown comics artists from before the "Yellow Kid" to the end of "Little Nemo."

Beyond Sunday Press, you also restore "Flash Gordon" for Titan. How did you get involved with Titan and what made you interested in working with them?

I knew the original Titan guys when they had the Forbidden Planet bookshop in London over 30 years ago. I've always had a great respect for their love of comics and their concern for quality, in their stores and publications. When I was approached by Titan to restore my collection for their books, it felt like a good opportunity to present Alex Raymond's stunning Sundays to a greater audience, and, using today's advances in digital reproductions, with greater quality and accuracy than in collections from past years.

I'm curious about any particular challenges unique to Raymond's work as opposed to some of the other work that you've restored?

Restoring "Flash Gordon" for print turned out to be more difficult than I first thought. The artwork and printing for "Little Nemo" was pretty consistent for the first incarnation of the strip, but during "Flash Gordon's" first two years, Raymond's inking style and the coloring of the strip varied greatly by comparison, sometimes from week to week. Even when working with just Hearst's "Comic Weekly," the home for all King Features strips, there was variation in the printing quality and the format, and the detailed work of "Flash Gordon" magnified these differences. It was a challenge to maintain a consistent look for the strip until the pages of 1936-37.

Another unrestored page from "Flash Gordon" (top) and Maresca's restored version

What goes into this process? Take us through having the original art and what's required as far as taking one page and turning it into a page in the book.

Everyone works a little differently, but I think the basics are the same and what follows is my process. Each page is scanned, in two pieces if necessary, using an A-3 scanner then digitally re-assembled. A rough color-correction is applied to remove much of the yellowing and give a clear picture of the page. Then, the physical defects of the page are repaired; stains from light, mold or water damage, holes or tears from binding, vermin or years of mishandling. Then the colors are fine-tuned with particular attention paid to the "white" backgrounds or colorless portions of the page. Even when new, newsprint was never white, so I like to create a look that will simulate the colors of a new, or slightly aged, newspaper. I never liked the strong contrast, bright colors and white backgrounds of strip reprints of the past. To keep the warmth of the colors found in the original pages, I separately adjust the colored and uncolored portions of the page.

Why not just reproduce it in black and white? I love black and white art, and I've seen Raymond originals and they're something to behold. I know that the color and how to approach the color is always a big question when restoring and reproducing old comics.

My main interest is in printing the comics so they appear as they were in the original papers, with the coloring that was used at the time. I don't think they are as interesting in B&W unless they were taken from the originals, and I'm pretty sure it's impossible to gather up a full set of those. Although it's always nice when reprint books do include some quality reproductions as part of their intros. But it would not work very well to print the pages in B&W from the color pages, there would be just too much interference with the linework.

The decision about the dimensions of the book, the paper, the book design -- how much of this was up to you, how much control did you have over those choices?

I made suggestions about the book size, given that Raymond's work had slightly different dimensions and for much of 1935 had a completely different format. But that decision was left up to the folks at Titan, and I think they made the right choice.

The third book collecting all of Alex Raymond's work on the strip has been released, and there's going to be a fourth volume with Austin Briggs' strips. Can you talk a little about Briggs and his work.

Briggs was the natural choice to take over for Raymond on the strip since he had worked as Raymond's assistant and drew the "Flash Gordon" daily strip. A marvelous illustrator in his own right, Briggs is often not given the respect of "Flash Gordon" fans for his work on the Sundays. Perhaps because he was required to mimic as closely as possible, Raymond's style, and even the finest illustrators would come up short there.

In later years, Mac Raboy was able to bring is own unique style to the strip, particularly with his use of blacks. But "Flash Gordon" will always belong to its originator, Alex Raymond.