In "Penny Dora and the Wishing Box" #2 by Michael Stock and Sina Grace, the Wishing Box is opened for use. It's clear from the events of the first issue and even just the title of the book that Penny has been given a box that will grant wishes. In "Penny Dora and the Wishing Box" #2, the plot advances very slowly, teasing out the possible consequences on a micro-level rather than leaping into any far-reaching changes. These baby steps squander a lot of the inherent suspense of the supernatural premise, but they also introduce a quiet tone of psychological horror that is at odds with Grace's cartoony and upbeat artwork.

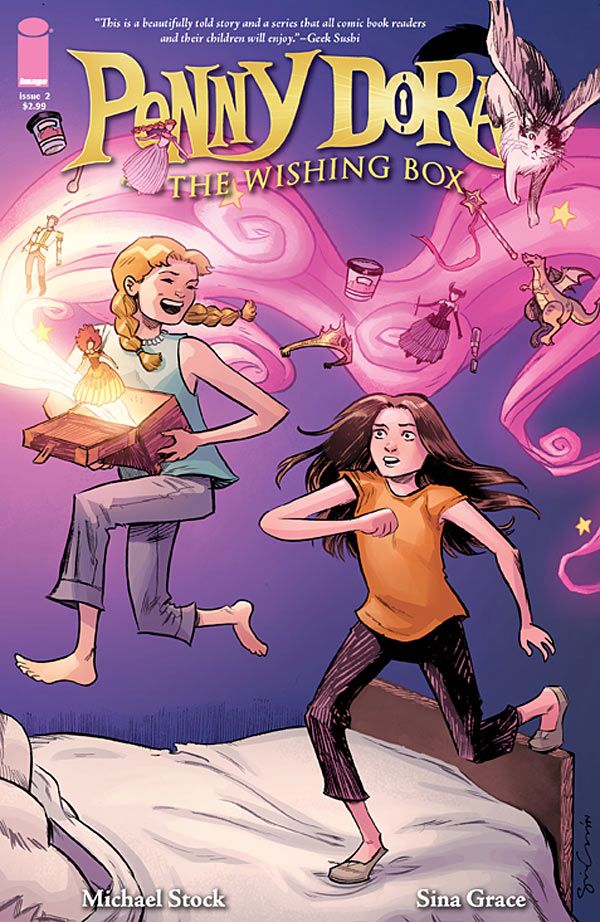

Grace's art is strong on transitions but his facial expressions and body language are stiff in some panels that could use a little more movement to them. He makes the girls look chibi in certain panels, and while the technique has the usual funny and cute results, it feels out of place. Stock's script doesn't have the same pacing and oversized hyperactivity that characterize the usual use of chibi in manga. Bonvillain's pastel palette matches Grace's cartoon sensibility but it likewise downplays the creepiness of Stock's script.

The most memorable parts of "Penny Dora and the Wishing Box" #2 are the moments that invite contemplation, like the creepiness when the box's voice changes to a softer timbre, or when Stock explains what is going through Elizabeth's mind and Penny's mind when the inevitable fight happens. Grace's portrayal of the girls dampens the horror aspects of Stock's script while playing up its all-ages appeal. The comic still seems to be finding its tone. The unusual mix of horror and whimsical kids' story is original, but the story elements are still working against each other.

Another concern is whether Stock can really add anything to a story based around this particular theme. In numerous fables and folktales, the recipient of the wishes always ends up realizing that they would have been better off not accepting what would be an endless source of power, because desires can't be asked in a way that can prevent unwanted side effects. The wisher is often undone by their own ambition or greed and is humbled by story's end. Like time travel, it's a plot device that can get old very fast, because the moral is always "don't tamper" or "too much power isn't something mortals can handle." So far, Stock's take on these themes seems to be headed in a conventional direction.

The unconventional part of "Penny Dora and the Wishing Box" is Penny herself. In the original Greek myth of Pandora, Pandora is very much like Eve of the Bible, innocent and impetuous and doomed to unleash evils upon mankind. Penny is innocent but she also has forethought. If caution and moderation are the virtues that the Pandora myth seeks to cultivate, then Penny Dora doesn't need those lessons. She's already cautious almost to a fault.

Most kids, and let's face it, even most adults, would be tempted to go hog-wild with wishing once they knew what they had. Penny has gone more than 24 hours without wishing for anything that could be considered personal gain. Penny is instantly aware of the creepiness and the immense power of the box, and it freaks her out instead of swelling her sense of power. Her more impulsive and curious friend Elizabeth is more typical. She's Penny's foil and when she fights with Penny, she also provides the first bad consequence of the box being used. In Penny's characterization, Stock's story may be headed in the direction of something new, but it's too early to tell. For now, "Penny Dora and the Wishing Box" #2 is an interesting but uneven reading experience.