Harvey Pekar's Cleveland was probably the perfect last comic from the legendary writer. Published in April, a little less than two years after the writer's death, it treated the setting of almost all of his works as the subject, and, intertwining biography with city history, it synthesized the the story of the man and the story of Cleveland into one. With beautiful art by Joseph Remnant, which evoked the best qualities of some of Pekar's best contributors, it was a pretty perfect punctuation at the end of Pekar's writing career.

And now here's another comic.

Not the Israel My Parents Promised Me, written by Pekar with Philadelphia-based artist JT Waldman (Megillat Esther), is seemingly on a subject far less associated with Pekar than Cleveland, one that can be incredibly controversial, as Israel's history embodies a sort of perfect blend of serious life-and-death issues that almost everyone is extremely passionate about. It's also, incidentally, not a a subject Pekar owns the way he owns, say, Cleveland; I don't necessarily seek out graphic novels about Israel and its relations with its neighbors, but in the past few years the following have come across my desk: Sarah Glidden's How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less, Joe Sacco's Palestine and Footnotes in Gaza, Marv Wolfman and company's Homeland, Rutu Modan's Exit Wounds and Jamilti and Other Stories and Guy Delisle's Jerusalem: Chronicles From the Holy City.

As suggested by the cover image, a drawing of Pekar regarding the reader, standing in a field of empty space filled only with the title and credits, this is actually another book about Pekar, Pekar's life, and Pekar's city; the "Me" and "My Parents" in the title are almost as — if not just as — important as the "Israel" in the title.

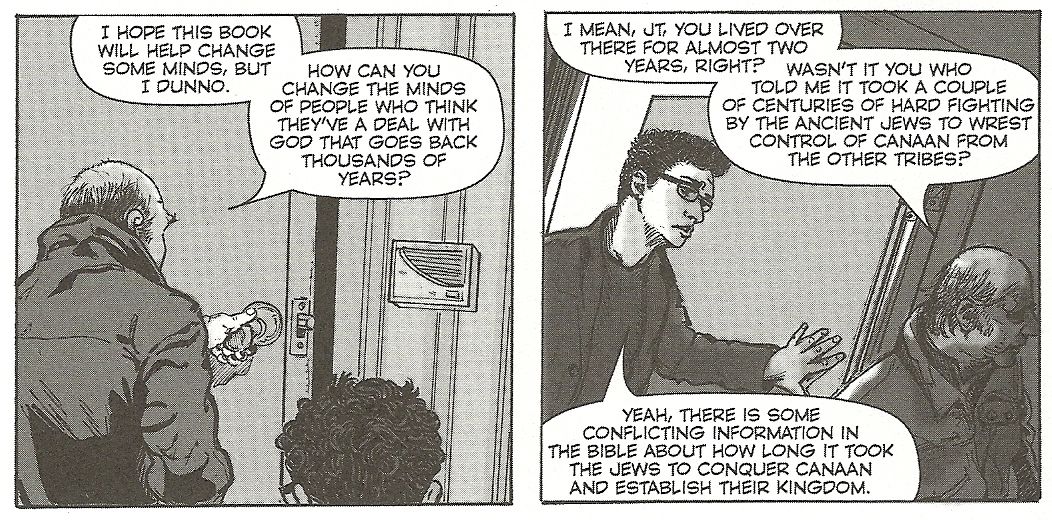

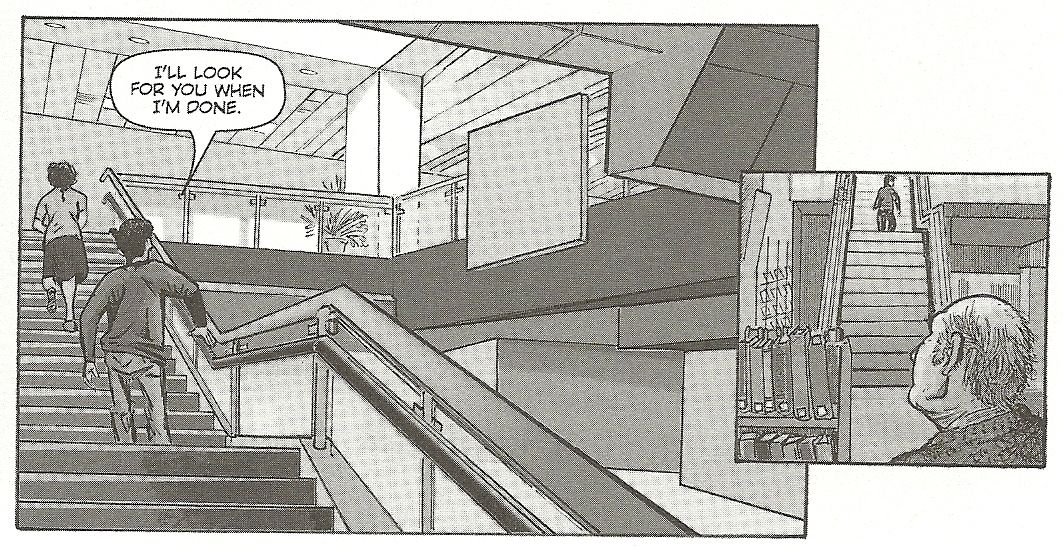

The book is framed as a conversation between Waldman and Pekar, about a book about Israel they're planning to write (in this regard, it's a little bit like Alison Bechdel's Are You My Mother?, a graphic novel about writing a graphic novel about her mother, albeit a much more linear version of the conceit). Waldman is in Cleveland visiting Pekar, who takes him to some of his familiar haunts, including John Zubal's warehouse used bookstore, "maybe the biggest used bookstore in the world," which was featured prominently in Cleveland, and the Lee Road Branch of the Cleveland Public Library System.

It begins with Pekar introducing himself to the reader in the street outside Zubal's, introducing us to Waldman and stating the thesis about as directly as a junior high student learning to write papers: "I'm here with my friend JT Waldman -- a wonderful artist -- to research a book we're working on about the history of Israel. I also want to explain why my attitude about the state of Israel has changed."

And from there the reader walks into the store with the pair, and listens to their conversation with one another and those they meet, that conversation usually taking the form of Pekar holding court. As Pekar tells his stories, of his parents, of his life and the history of the Jewish people starting with the stories of the Old Testament, Waldman's art shifts from panels depicting the pair hanging out to illustrations of Pekar's parents and childhood to Biblical stories. Despite the direct, dot-connecting storytelling, the art is pretty inventive, shifting not only in subject matter, but also in style, as Waldman conjures both modern-day and 20th-century Cleveland, and tailors his illustrations of the history lesson portions to appropriate styles: So when the ancient world is discussed, his drawings ape the look of hieroglyphics, tile art, Persian art; when we reach the Middle Ages, it looks like that of tapestries and illuminations; by the 1940s, World War II propaganda posters, and so on.

Even a stretch of the pair driving is rendering in panels whose borders are trimmed to resemble a somewhat winding road, shrinking the space of the page to something more cramped and intimate (like a car), while the outside world disappears into white space.

Pekar never went to Israel, despite an attempt as a young man to emigrate there (they wouldn't have him). His feelings and opinions about the nation actually predate its founding, however, as his Jewish parents, who lived in a Jewish neighborhood (in the 1930s and '40s, Cleveland had a population of about 85,000 Jews, and Yiddish was spoken on the streets of their neighborhoods rather than English), followed closely the events of the diaspora in Europe and the Middle East.

As a gentile American in the 21st century, it's not all that difficult to find things to be disappointed in when it comes to the conduct of the state of Israel, but Pekar's disappointments predate, say, the Second Intifada of 2000-2005, but go all the way back to the aftermath of the 1967 war and the beginnings of the controversial settlements programs ... which still continue.

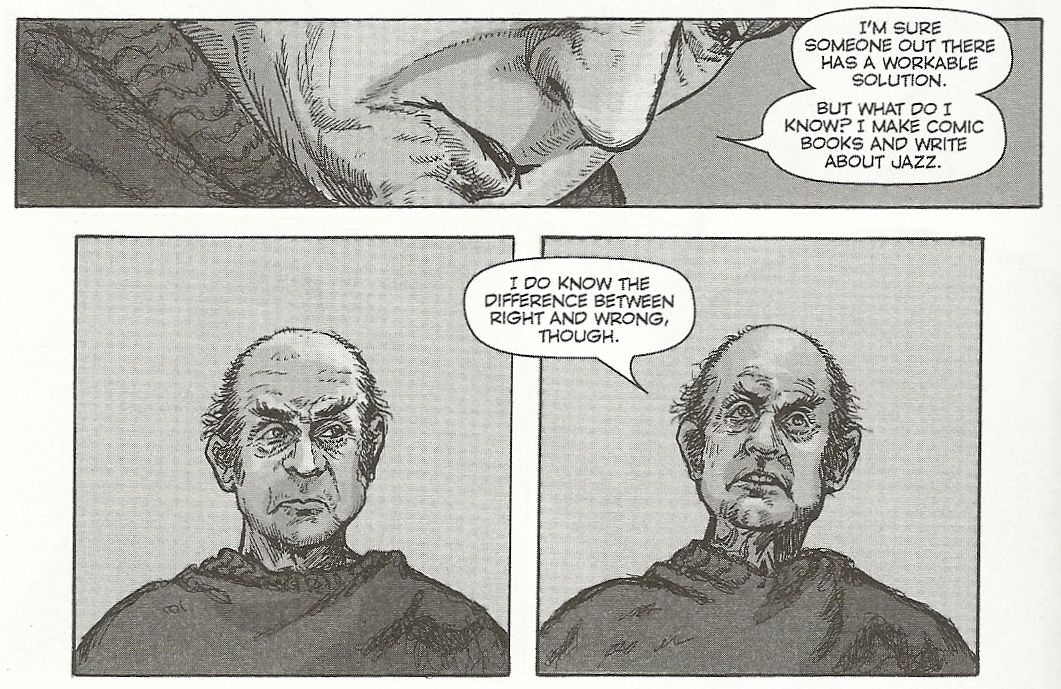

Pekar has a point of view, as does Waldman, but they offer no solutions (during their climactic conversation, the mode Waldman chooses for the artwork is a complicated maze pattern running between images of the pair talking). Pekar makes some rather broad statements, of the sort that seem infinitely sensible to someone as far outside of the conflict as, say, a non-Jewish, non-Muslim, non-Arab, American citizen living in a different hemisphere. ("Jews oppressing others just to survive seems dicey," for example, or, "The Palestinian Arabs are not going anywhere," or "But if the main issues...aren't discussed, it's hard to image progress being made.")

The pair somewhat deflate Pekar at the end, with a pretty effective gag that reveals that, despite his strong opinions and decades thinking, worrying and occasionally writing about this stuff, he's human too, and suffers some of the same foibles his parents and family members did. The Waldman character, for his part, attempts to make a joke about space travel and exploration.

The conversation then trails off, as the two temporarily part, and Waldman leaves Pekar sitting in his favorite place at his favorite library, thinking. It's a somewhat devastating ending, given that we now know Pekar's life would end shortly after that, and an ending that probably wouldn't have existed were this not a book being published posthumously. It includes an epilogue written by Pekar's widow Joyce Brabner, a six-page comic drawn in soft, light pencils by Waldman. In it, Brabner discusses her non-existent relationship with Pekar's parents (one died before she met him, the other was suffering from Alzheimers), their attendance of a funeral and her funeral for him, colored by that previous experience at a family funeral. It inevitably brings things back to Pekar's relationship with his faith and his ancestors.

It would have been nice if Israel and its neighbors could have solved some of their most pressing problems before the end of Pekar's life, if he could have seen at least a glimmer of the Israel his parents dreamed of when he was a kid. But then, there are a lot of things one wishes might have happened before Pekar passed away.

The epilogue also serves as a sort of punctuation, a reminder that Pekar is no longer with us and this is maybe his last new work that will see print. If you haven't read either yet, I'd still recommend you read this before Cleveland, as Cleveland still strikes me as a better last Pekar comic (if there must be a last Pekar comics). But whatever the order, do read them both.