During the past several decades, rock music – that is, true hard rock -- has in a lot of ways become a punch line as a genre, due to the interpolation of different instruments and elements, not to mention the rise of pop versions of the stuff that used to melt faces, so to speak. But since his days in the 1980s as guitarist for Guns N’ Roses, Slash has been a standard-bearer for rock ‘n’ roll, and a purist who defended its integrity by producing music that lived up to the intensity and artistry of its founders.

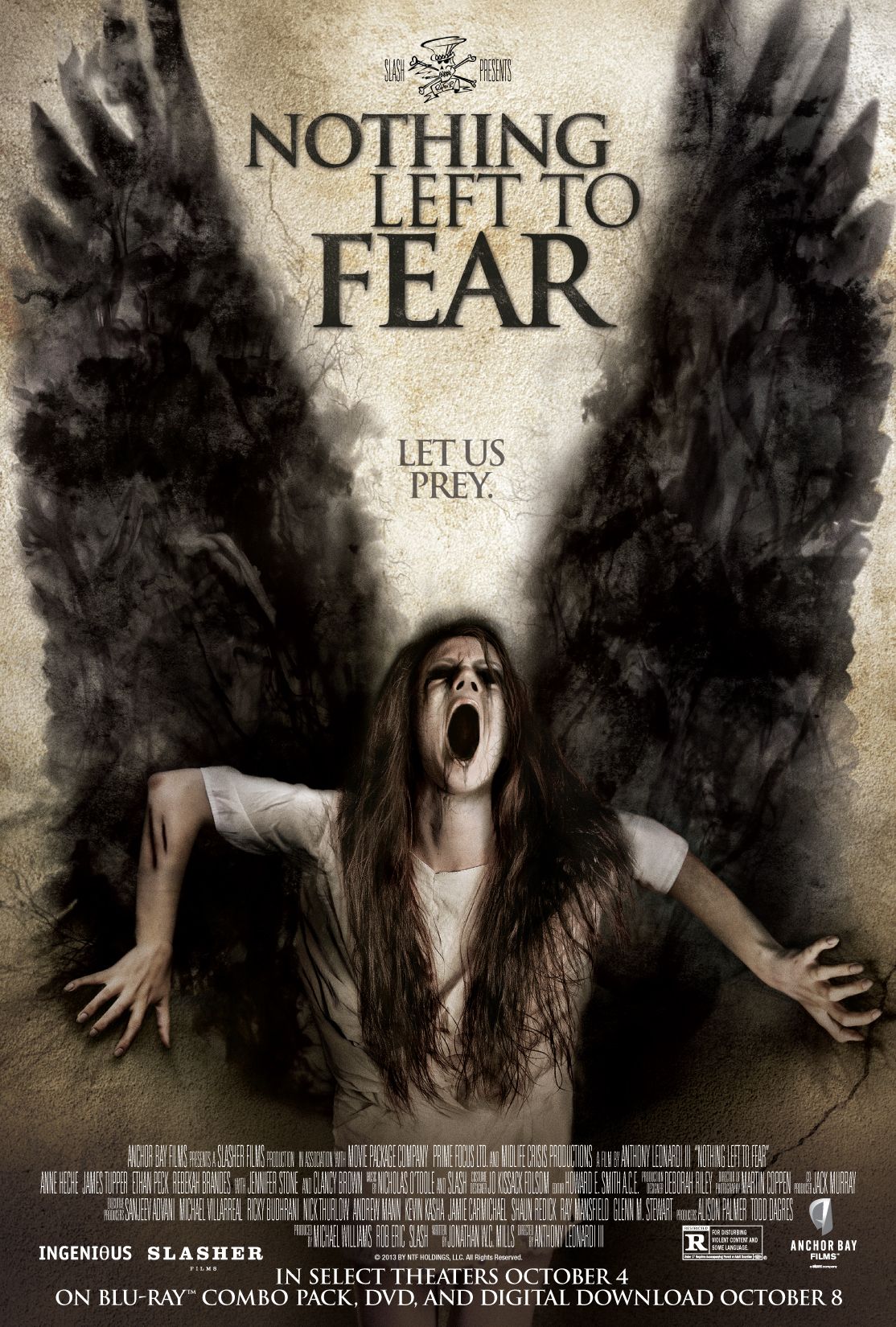

But some 25 years after Appetite For Destruction became the bestselling debut album of all time, Slash is trying to be a purist for another art form – namely, filmmaking. And he makes his debut as a producer with Nothing Left to Fear, a horror movie that avoids pointless, graphic violence in favor of deeper, more resonant storytelling that comes from a fantastical but remarkably human place.

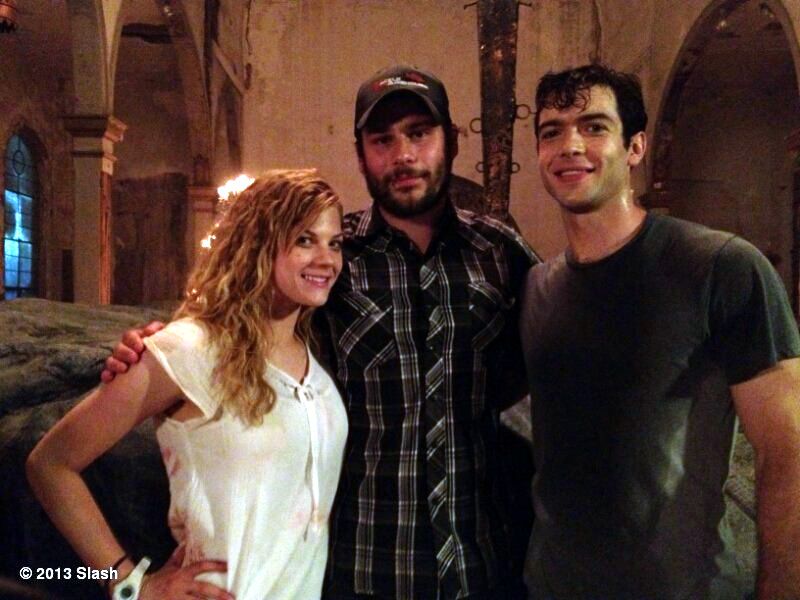

Spinoff Online recently sat down with Slash and director Anthony Leonardi III in Los Angeles to talk about his role in the new horror film, which debuted Tuesday on Blu-ray after a brief run in theaters. In addition to he and Leonardi talking about what drew them to this particular film, Slash discussed his ambitions with the genre, and then offered insights into his motivations for making this transition from music to film.

Spinoff Online: Anthony, what were your initial ideas about this when you decided to take this on?

Anthony Leonardi III: When I originally read it, I wasn’t looking for something in the horror space, and I didn’t want to do a slasher movie. But this story came to me and I read it, and what was really interesting was the element of relocation – a family moving to a new place – and then this finding out that they’re trapped and it’s all meant to be. I think there’s a natural fear in all of us in going to a new place and not knowing what’s going on.

Slash: Yeah, it definitely is for me now (laughs).

Leonardi: So I went in and I pitched it – this is what I want to make, and we hit it off from the get-go and just went on from that.

Slash, what did the two of you talk about that got you excited about taking this film on as your first effort as a producer?

Slash: I was over a period of time given tons of scripts by my partner, and when I finally whittled it down to a small handful of scripts, Nothing Left to Fear was one of them. There was something about this sort of innocent, young family making a leap of faith from the city to this small, rural community, under the guise of religion, only to find out that it was for a more sinister purpose that they were there. And I loved that there was a monster involved. But I loved its simplicity – it wasn’t like, OK, we’re going to take you on a multitude of twists and turns and play brain games with you. It was really straightforward and to the point. So it just stood out as the one to go for, and it seemed like one of the movies that could be done a quality job with a reasonable budget.

Slash, you contribute music to the film. Since this is a new venture for you, did you have any reluctance to do that, or did that help make the move from music to film a natural transition?

Slash: No. When I got into the producer position, a lot of it was riding on the fact that I would be involved with the music. I mean, that was part of the attraction for me, that I would be involved with the score, but I was very realistic about I don’t want it to be about kicks and giggles, Slash’s opportunity to put guitar over every movie he produces. It was about getting the right marriage of the right music with the right story. And so, from the onset, I said, well, I want to write something – I have ideas for some melodies for it, but it needs to be an orchestral thing. It needs to be composed with strings and so on. And so I just accepted that right away, and Anthony introduced me to a friend of his named Nicholas O’Toole, who is a great composer and sound designer, and I worked with him solidly throughout the whole process.

REVIEW: Nothing Left to Fear Cleverly Conceived, Clumsily Executed

Notwithstanding the obvious commercial appeal of the genre, what was the appeal of producing a horror film as opposed to, say, a drama or some other kind of film?

Slash: My whole reason for getting into this was basically to do something that the genre of horror is lacking. I love all types of movies, but my sort of personal passion is definitely horror, so when I was given the opportunity to produce, it was to sort of fill a void that I saw personally in the genre.

Why do you think it is that rock musicians seem to have such an affinity for horror movies, whether it’s just a love for the genre or actually getting into making them like you’re doing?

Slash: As far as musicians go, I only know a couple who I call are actively in the horror-themed thing: there’s Alice Cooper, Rob Zombie, and one of probably the biggest closet horror collectors, Kirk Hammett [of Metallica] – who has everything I ever wanted as a kid (laughs). I’m still jealous of him. Each of these guys probably has their own story, but I think the one thing we all have in common is that we all loved horror movies as a kid, especially Alice, because he does basically rock-horror theater. That’s his whole trip, and it always has been. But I think we were all attracted to that, and I find that horror is pretty universal in the metal scene, because it all deals with the occult or it deals with some sort of satanic something-or-other – and horror speaks to that. And I think that rock ‘n’ roll is great theme music for horror. But the twain meet on the same ground somehow, and we’ve been calling it rebellious attitude at this point – they just have that one thing in common, where it’s freedom of expression that’s not mainstream. It’s kind of speaking about the darker sides of the way that we think, and you’re able to do that with music. You’re able to express stuff that you wouldn’t be able to express if you were Perry Como. And with horror, it’s the same thing: It’s not mainstream, and you couldn’t put that stuff into sort of every Ron Howard movie or whatever. So it’s this like dark thing that we get to be able to express, and there’s an avenue to be able to do it.

Producing is often described very ambiguously. What sort of contributions did you want to make, and what was your collaboration like with Anthony?

Slash: From the get-go, I wanted to be involved in every possible aspect, creatively. I can’t say that I’m all that interested in it from a business point of view; I have a partner, fortunately, who covers that and is very good at it. So everything about producing the movie, from developing the script to Anthony directing, casting and locations, I was interested in everything. And then with Anthony, it was open of those things that when we first met, we had an instantaneous meeting of the minds as far as what the story was, and that’s what made it happen for us. Like when I first met him, out of all of the directors I met, he had a vision of the whole movie and I related to that right away. And so there was a lot of latitude as far as what Anthony could do with this, because there wasn’t an argument as to what movie we were making, and I trusted him.

Having done small roles in films even as far back as the 1980s, were there any qualities you gleaned from producers that you wanted to bring – or maybe not bring – to this film when you were in the role?

Slash: I definitely have tons of insight as to why I do not want to be an actor (laughs). I think I even have some insight as to why I wouldn’t necessarily want to be a director. But as far as a producer is concerned, the only real role model that I had for producers that I had was Robert Evans, and he’s a great role model if you want to be a producer (laughs). But really, up until the day that I was approached with the idea, I never thought about it. It never even occurred to me, and I didn’t have a lot of information, historical information, about producers and directors, that I really had to draw from. I really went into this with a sort of open mind and a clean slate.

Anthony, how would you characterize your collaboration?

Leonardi: I think it was an ideal creative collaboration. As a director, you have to find producers that want to make the same movie, because if you meet and you both want to make different movies, it’s not going to end well. So from the moment we met, we kind of collaborated around the same vision of the movie, and then as budgets changed and different elements changed, we had the same movie in mind, so it was a really good creative support to get to the end, no matter what issues came.

How much of the film’s mythology did you want the audience to know, and how much did you want to keep as a mystery?

Leonardi: The problem with movies like this is the more mythology you try to nail down, the more holes you find. But the cleaner you can make a mythology without getting into crazy details, especially in 90 minutes, the easier it is to make. Because it’s even like Stull [Kansas] – as soon as you look it up on the Internet, you find a hole, and you look up that hole, and you find two more. It’s like looking at Bigfoot – you’re always going to find some hole somewhere – so it’s kind of like saying, in this town, we’re not even putting a date on it, but the town shuts down and this happens. And if it doesn’t happen, all hell breaks loose. What hell breaks loose? We’re not going to tell you. And I think it keeps it a little more terrifying that way.

Slash: Ironically enough, there’s a mythology that goes along with the town of Stull in reality, and we didn’t use any of it, much to the pleasure of the residents of Stull. But once this comes out, they’ll be really happy that we just used the town’s name, but we didn’t get into the sort of folklore about what actually happens there.

Do you see this film’s climax as hopeful or pessimistic?

Slash: Interesting – that’s what Clancy [Brown] asked me.

Leonardi: It’s funny because that’s what really attracted me – I wanted to do a movie where it was not black and white, like bad guys and good guys. In what happens, you should think, “Would I do that to save everything?” So, the end of the movie is optimistic because they [redacted], but it’s terrifying because what happened had to happen to do that. And it fits in the story; there was never a moment where we added [violence] just to be gratuitous, like, oh, we want to show some arms being ripped off. All the deaths have a certain way they’re done, and we never wanted this to be grotesque. But I think it’s what it should be, and when I first met Clancy, I was very afraid he was going to come in and play the bad guy – he’s a big, brooding man, and he can be very scary and he just played this dark preacher on Carnivale. So he comes in and he goes, “I really feel bad for this family, and I’m really terrified that this has to happen to little kids. But I understand it.” And I was like, that’s the character – that’s it, that’s our bad guy right there, because he’s not really bad.

Slash: He’s almost like a sympathetic character.

Leonardi: They’re very sympathetic. The way I wanted to structure it was like, if anyone in town could save these people, they would.

You obviously don’t see this as a one-time venture. What do you have in mind for what you want to do next?

Slash: Well, we both want to do stuff, so I’m looking for stories and trying to see if I can find something. I don’t want to pigeonhole myself into one thing, but I’ve been really interested in finding a good monster story, and going in that direction, because nobody’s done a good monster story in decades. And then I’d like to do something with [Anthony] again, because we’ve done this, and to take it to the next level would be great. So really it’s a matter of just finding material.