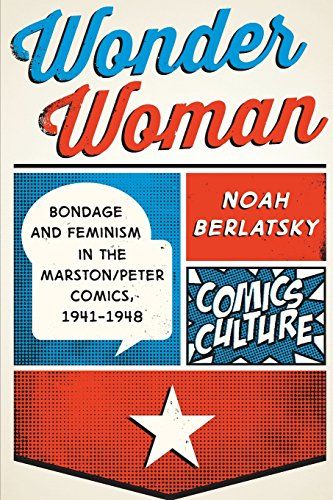

Noah Berlatsky is a name that may be familiar to those who read about comics. He regularly writes about comics, culture and gender for many publications including The Atlantic, Slate, Salon and Reason. He serves as the editor of the popular comics and culture blog The Hooded Utilitarian and he's also a contributor here at Comic Book Resources, where he's written about everything from the relevance of Adam West's "Batman" to "Ms. Marvel's" depiction of violence. This month, Berlatsky can add one more credit to his lengthy resume: published author.

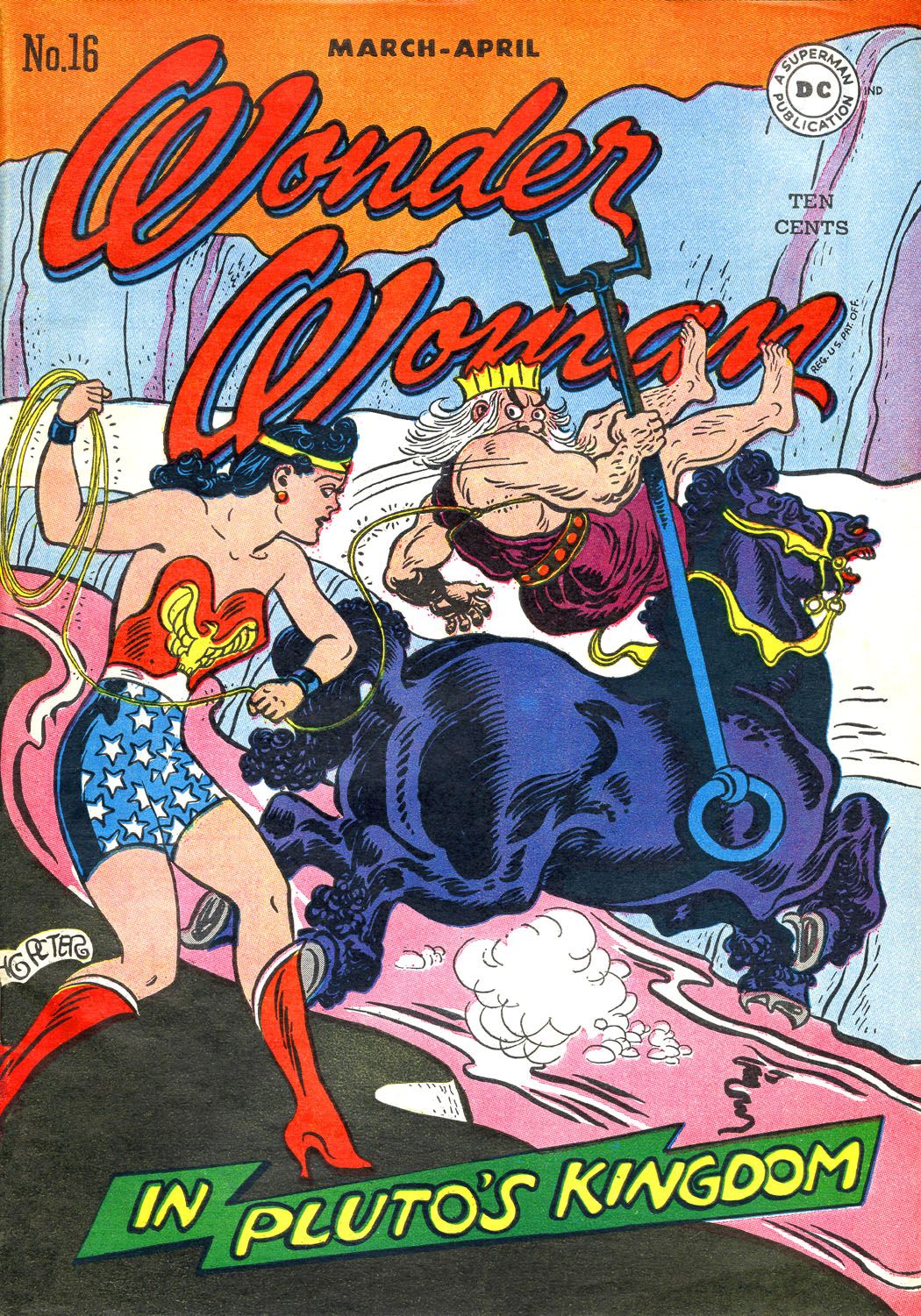

Rutgers University Press will soon publish his first book, titled "Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peters Comics, 1941-1948." The book -- as Berlatsky makes clear in its introduction -- is not interested in Wonder Woman the icon. Instead, the book focuses on the Wonder Woman comics that William Marston wrote and Harry Peter drew. Berlatsky looks at the comics, with an emphasis on "Wonder Woman" #16 from 1946, which he argues are unique works of art that still hold a great deal of relevance today. Now that the issues of feminism and representation in comics are being treated more seriously than ever, Berlatsky makes the case to CBR that Marston's "Wonder Woman" comics should be essential reading.

CBR News: I remember reading some of your articles about Wonder Woman on the Hooded Utilitarian, which is where the basis of this book started years ago. Where did your interest in Wonder Woman start?

Noah Berlatsky: I'm not especially a fan of Wonder Woman or interested in Wonder Woman in general. I think I saw the TV show once or twice and was not especially taken with it. I'd read a couple of Wonder Woman comics -- which, like most Wonder Woman comics, were pretty bad. It was Dirk Deppey at Journalista, the Comics Journal blog, who got me interested. He had some segments about the original Wonder Woman comics and I think it was the segment where she was in a gimp mask and had to bite through it while thinking about the history of bondage in France. I was like, "What in the world is this?" [laughs] I was looking for the original series and I think I found it on torrent because they're not really reprinted. DC has done a couple of reprint series, all of which have stopped before they got to the end [of the Marston/Peters run].

Reading the Marston/Peters run, they are something completely unique. There's nothing quite like it -- including almost all the Wonder Woman stories that have followed.

Little bits stick out. I remember reading a "Superfriends" comic when I was a kid and there was some segment where Wonder Woman loses her bracelets and goes berserk. That's something from the Marston/Peter era and as a kid I remember thinking, "What is going on?" Bits and pieces remain, but yeah, they're very different -- not just from Wonder Woman, but from anything in the superhero world or really anywhere. There just are not very many comics that are about trying to teach kids about the joys of bondage, feminism and lesbianism. That's not something that very many superhero comics attempt to do.

You have a great line in the book's introduction that reading Wonder Woman in the context of comics is like reading Freud for the plot -- it misses a lot. It's a funny line, but it's very true.

Yeah and I'm not the only person to say that. ["Secret History of Wonder Woman" author] Jill Lepore talks about how it's important to see Wonder Woman in terms of the history of feminism in her book, and I think that's right. It's partially why in terms of the DC Universe, nobody has really known what to do with the character. Putting her into regular superhero stories -- it's like, why bother? Superman and Batman are basically pulp adventure characters. As long as you put them in pulp adventure, it's fine, but Wonder Woman is really about this utopian vision of feminism and kink.

There are some similarities with other characters who had very specific artistic visions. Plastic Man doesn't make a whole lot of sense in terms of the DC Universe either because the original comics actually had an aesthetic of their own. There are some parallels with some other characters, but the Marston/Peter comics are very unique in terms of what they're trying to do and how they're trying to do it. It's very different from other superhero comics and, as a result, I think it's been difficult for people to figure out what to do with Wonder Woman.

I think that's one reason why Jill Lepore's book took off, because -- as you make clear -- all these issues and ideas aren't even subtext. They're text.

Jill Lepore was somewhat reluctant to talk about the bondage or the fetish or the kink. She doesn't really talk about lesbianism in the comics. For a lot of people, there's a tension between sex -- and sometimes even sexuality -- and the feminist message. People have tended to emphasize the feminist message and explain away the bondage in various ways. I mean, everybody can see it's there, but you say it doesn't matter. ["Wonder Woman" artist] Trina Robbins has said there's not any more bondage [in "Wonder Woman"] than in Shazam or other comics of the era. ["Wonder Woman Unbound" author] Tim Hanley, in his book last year, went through and counted panels of bondage and showed there is a lot more in "Wonder Woman" than anywhere else. In that interview with you, Jill Lepore ties the bondage imagery to discussions of feminist bondage imagery and breaking out of bonds, which is there, but then why is Wonder Woman constantly tying people up?

Jill Lepore Reveals "The Secret History Of Wonder Woman"

It doesn't explain why Marston was so specific and detailed in terms of how things were depicted.

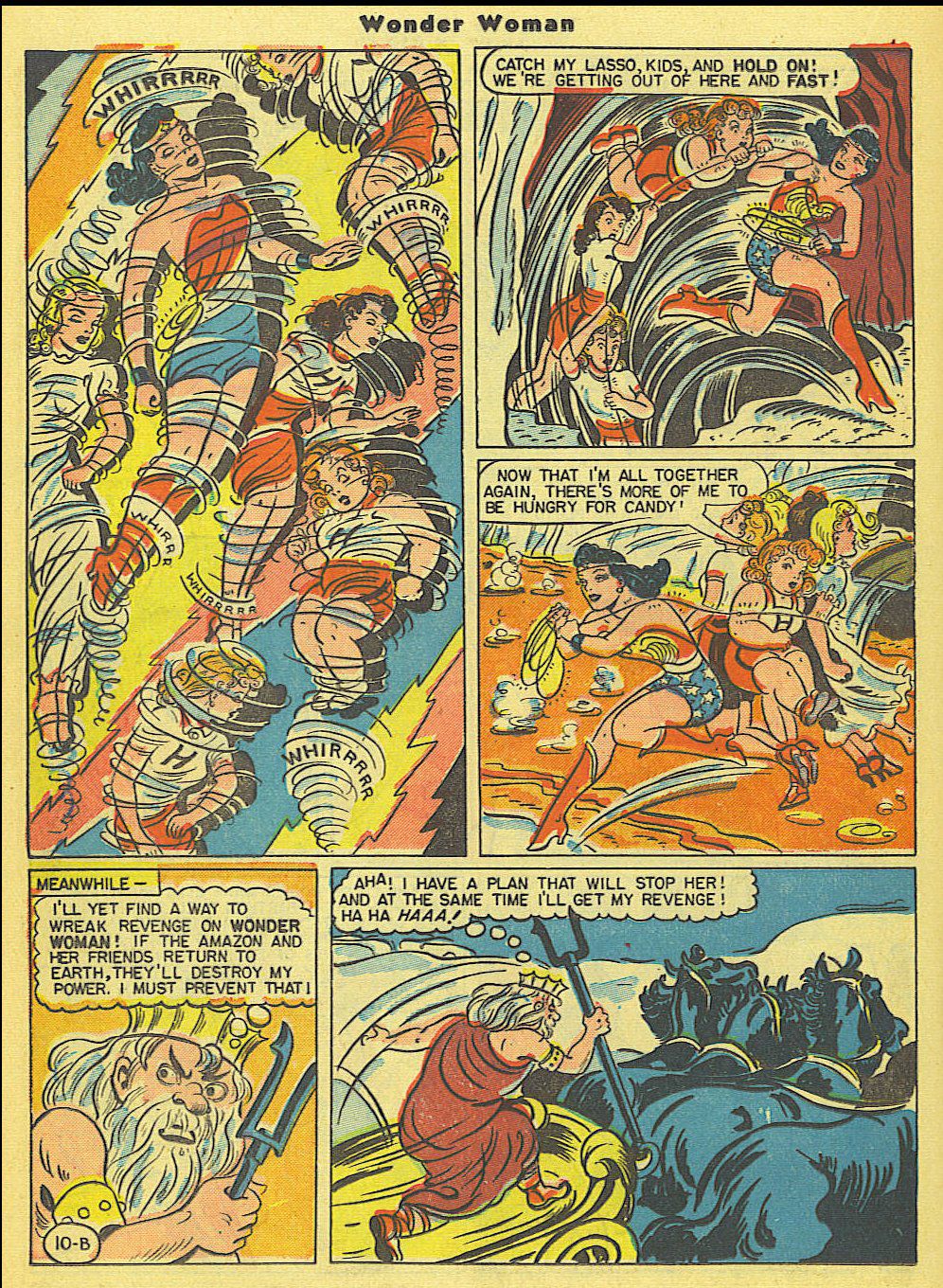

Exactly. It doesn't explain all the imagery -- why there's all this mind control and pink bondage tentacle goo. Jill Lepore talks about this elsewhere, but Marston's other writing is all about how women love leaders who are going to force us all to submit and bring about utopia. The bondage in the comics has theoretical weight. Marston talks very openly about his sexual interests and how they're related to bondage and lesbianism. My point is that the feminism and the sex are very important to Marston and to the comic. That makes them different from anything anyone else has done with this character -- or any other superhero pretty much.

It was interesting reading both your book and Jill Lepore's because you're both very interested in feminism, but you have very different and complementary approaches.

I would say, briefly, that the big difference is that for me the interest is the comics. I think the comics are great art. That's what inspires me and that's what interests me, whereas for Lepore, the comics are at best a secondary interest. She doesn't see them as noteworthy in terms of works of art. She's much more interested in connections between Marston's family and Margaret Sanger and the milieu of early twentieth century feminism. I think those are the main differences.

You spend one long chapter in the book looking at "Wonder Woman" #16 from 1946. I haven't read it but I really want to now, because it's just fascinating.

That's the heartbreaking thing about these comics to me. They are some of my favorite art ever and they're just not available. I think #16 may have been reprinted in the archive editions, but for the most part the comics are not very available. People haven't read them.

At what point did you know that that issue would be the one issue you deconstruct like that?

I read all the issues of "Wonder Woman" and that was my favorite. I knew I wanted to talk about one comic closely at great length. I talk about several comics, but I really wanted to look at this one in particular. I think it's so wonderful, but also because I am trying to make the argument that these comics are worth thinking about as art and have things to tell us -- in this case about issues of sexual violence and sexuality. One of the things that Marston is trying to do -- with [his assistant-turned-writer] Joye Murchison and Harry Peter -- is talk about sexual violence to an audience that is composed mostly of kids. They're talking to young girls and boys, so they're talking about sexual violence but also trying to talk about the way that sexuality or sex can be fun and good. They want to show the evil of sexual violence while showing the value of sexual fantasy, which is a really tough thing to do!

That's at the heart of a lot of struggles around sexual violence in our culture, particularly in Freud. Freud had two different theories of sexual violence. One of which was that women who were traumatized were traumatized because they'd been abused. Then he switched that around and said maybe the problem is that they're fantasizing about having sex with their fathers rather than that they've been abused. Those two end up being mutually exclusive. Sexual violence and sexual fantasy end up as things that Freud sees as irreconcilable. It's very difficult to think about sexual fantasy as a healthy okay thing and sexual violence as this horrible traumatic event at the same time and not privilege one over the other. I think Marston and Murchison and Peters are trying to deal with those issues in a comic for kids -- that includes space kangas! I think they have really profound and interesting things to say about that. I thought that was worth talking about at length both because what they have to say is worth saying and because people don't usually read these comics as if they are works of art that could move us or have something to tell us about important issues. I wanted to talk about it at length because I thought it was worth talking about at length -- and I wanted to try to show that these comics are really wonderful.

Marston made Wonder Woman this complicated character with a lot of contradictions. She's a princess who's blessed with beauty. She's a warrior who's charged with bringing peace. She's super intelligent but can kick everyone's ass. There's a lot going on with the character that can be hard to reconcile.

One of the things that ["Do The Gods Wear Capes?" author] Ben Saunders talks about is that Marston's Wonder Woman is not angstful. Superheroines and superheroes in general tend to be full of angst. Wonder Woman doesn't have angst. The first thing she does with her lasso is to make the Amazon doctor stand on her head. She's like, "Cool, I have this lasso." There's no angst. It's fun! I really like that about the comic. She likes having adventures and fighting evil and thinks it's great. That's one thing that makes her difficult for latter day writers. Angst is so important now to female heroes.

In terms of the other contradictions, Marston had particular ways that they made sense to him. It was World War II, so you could make a coherent argument that you were fighting on the side of peace if you were fighting against the Nazis. Other people made that argument. If [noted ethicist] Reinhold Niebuhr can make that argument, why not Wonder Woman? [Laughs] We're not fighting the Nazis anymore and so that particular syllogism doesn't map as well. Not that I necessarily agree with Niebuhr, but it's a coherent argument that makes more sense than saying, "I'm going to fight for peace and then beat up supervillains." The same thing with the bondage and the feminism. It looks like a contradiction to a lot of people from our vantage point, but to Marston, loving submission to women was the basis for feminist utopia. It all went together for him. I think the reason that there are contradictions that are difficult to resolve or deal with is because the ideology that underpinned them was Marston's and people aren't necessarily willing to sign onto all that. Reasonably enough. Not that everyone should adapt Marston's particular idiosyncratic views, but Wonder Woman doesn't make as much sense without them.

As much as it's a question of Wonder Woman being specifically Marston and Peter's character, I wonder how much the character was tied to that period.

I see Marston and Peter as great artists who made great art. Shakespeare was a product of his time. Those plays had something to do with when he was. Why didn't people write Shakespeare plays after Shakespeare died? Because he was dead. I feel the same way with Marston and his work. The reason the comics were very different after he left is because he was dead.

As people who read the Wonder Woman series on Hooded Utilitarian, you've read a lot of other Wonder Woman comics. You're not writing about them in part because you just don't find them interesting -- to put it delicately.

[Laughs] Correct. They're mostly bad. There aren't any other Wonder Woman comics that are in any canon of best superhero comics. There are various latter day Batman comics that are considered very well done and a handful of Superman ones, but there aren't any especially good latter day Wonder Woman comics, I would say. There are ones that people have more or less fondness for, but I haven't been taken with any of them myself.

You talk about one issue of Gail Simone's run in the book, which you find very problematic, but you enjoy some of her run.

There are fun things about her run. I like the intelligent gorillas fighting aliens. Super gorillas fighting Nazis are fun. I like her wit. She's a funny writer.

The fun seems to be the first thing most people throw out even though Marston and Peter were interested in making a fun book. I mean, there are kangaroos!

There were! They're kids comics, while much of the latter comics -- even [Robert] Kanigher's -- seem to be aimed at older readers. The Marston and Peter comics are loopy fun. She's flying to distant planets and there are kangaroos and giant rabbits and mole men. It's like Oz. It's about going to these fantastic landscapes and different worlds and exploring them in a way that has more to do with fantasy children's stories than what we usually think of as superhero adventures

You wrote something on Hooded Utilitarian: "Some ideas are so obvious they're brilliant. And then, some ideas are so obvious they're just fucking stupid. The Superman/Wonder Woman pairing is one of the latter."

[laughs] That's a horrible idea. The fact that that's become so central is just depressing. Wonder Woman isn't supposed to be somebody's girlfriend. She's supposed to be the thing. She's the hero. She's the ideal. Marston has one story where Steve becomes super strong and Wonder Woman thinks, "Well, it is attractive that he's super strong." But then she thinks, "Nah, I'd rather not date someone who's stronger than me." [Laughs] That's totally Marston. The guy is not supposed to be the dominant one.

"Wonder Woman Unbound" Reveals Complex History of Beloved Feminist Icon

I think she's going to be sweeties with Superman in the movie and what can you say? It's entirely contrary to Marston. Wonder Woman was a rethinking or a criticism of Superman. Marston wanted the strongest hero to be a woman. That's the point of Wonder Woman. The perfect human being is not a guy. It's one of the central points. To then have the central story be about how there's a stronger guy and Wonder Woman is supporting him is just totally wrong from Marston's perspective. It's just a much more boring, conventional way to think about what heroes are. The heroes are always guys. That's the default. The women are always off to the side helping them out. It's just a really bad idea.

I have spent more time reading Wonder Woman comics and reading about Wonder Woman in the past year than in the rest of my life. My reading of Marston is that he was presenting Wonder Woman as an ideal, but the historical essays and comics were showing that there have always been female scientists and scholars and warriors and you can be part of this tradition. In other words, you don't have to just cosplay as Joan of Arc, you can lead your own army.

I think it was definitely meant to inspire women and show that women can be heroic and leaders. I think that one of the interesting things about the way he does that is that Wonder Woman is not just aimed at girls. Often you have male heroes who are seen as universal. Superman is meant to inspire not just boys but girls. Women are supposed to identify with male heroes in general. Often female heroes are seen as specialized or they're meant to inspire girls and women, but for Marston, everybody should be a woman. Everybody should strive to be like Wonder Woman no matter what your gender. She is an ideal, certainly for girls, but for boys as well. He has this idea where everybody can be sisters. Everybody can strive to be great women like Wonder Woman -- no matter what your gender is. It's aimed at everyone because Wonder Woman is an ideal for everybody.

After reading the book, I really want to read these Wonder Woman comics.

Well good! I'm hoping people will come away from this and say, "I want to read these bizarre, wonderful comics for myself!"