The golem, an artificial being usually created from mud or clay and endowed with life, has appeared in stories of every media since ... well, since about the time people started telling stories, particularly if you consider the biblical first man Adam to be a form of golem ("And the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life," from the second, less poetic of the two creation stories in Genesis).

But there may be no medium better suited to this creature of Jewish folklore than the American comic book, as the most famous of golems, the Golem of Prague, was in many ways a prototypical superhero. That golem was supposedly created in the late 1500s by a Rabbi Loew to defend the Jewish people of his city from pogroms, and there you have a few of the basic components of the American superhero: the bizarre origin, the defense of the oppressed, the home turf in need of protection and, of course, the Jewish nature of the character's identity (often sublimated or coded in the early American superhero comics).

It is, of course, impossible to tell exactly how present in the backs of the minds of the many, many Jewish men who created the American comic book industry some 100 years or so after the legend of the Golem of Prague started appearing in writing in the third and fourth decades of the 19th century. But looking back, and looking for them, it's easier to see them, from Superman as a sort of Golem of Metropolis to the stony Ben Grimm of the Fantastic Four.

Michael Chabon's 2000 novel The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, about those early days of American comics, includes a passage linking the inspiration for its superhero The Escapist with that of the Golem of Prague. James Sturm's graphic novel The Golem's Mighty Swing features a version of the character inspired by the Paul Wegener silent film. The various stabs at Ragman comics since Joe Kubert and Robert Kanigher's initial attempt have tied the character to the Golem, and the short-lived DC Comics series The Monolith by writers Justin Gray and Jimmy Palmiotti featured a golem as its star.

Not convinced? No worries. I would like to point out a pretty excellent new comic about the Golem, so whether or not you believe the creature is woven into the DNA of comics and the superheroes that sustained the medium, here at least is another example of a golem in comics.

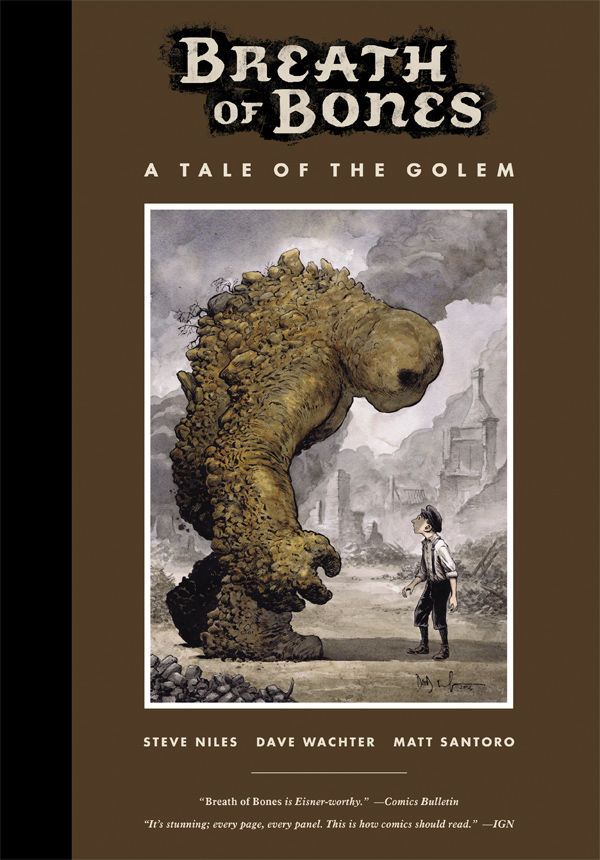

Released this week in hardcover, Breath of Bones: A Tale of the Golem is a collaboration between writer Steve Niles, best known for the horror franchises 30 Days of Night and Criminal Macabre, and Matt Santoro. They share a story credit, while Niles handles the script. The art comes courtesy of Dave Wachter, and it's likely that is what will attract and keep the attention of most readers.

It's a fairly straightforward updating of the classic Golem of Prague narrative to a much more recent time in our history when European Jewish communities found themselves in need of protection: World War II.

It opens on a muddy, bloody battlefield of 1944 with narration by a soldier named Noah, who knows the war is near its end, but still finds himself fighting for his life. Pinned down and separated from his unit, he begins to reminisce about when the war really started for him, flashing back to his childhood in an unnamed village in an unnamed country.

Shortly after the town of his childhood empties itself of its able-bodied men, off to fight the invaders and never returning, a British plane crashes in a field near the home of Noah and his grandfather Jacob. They hide the pilot, knowing it's only a matter of time before the Nazis see the smoke and come looking for the wrecked plane and the body that should be within. When the inevitable happens and villagers discuss what they should do, Jacob says they first must help him in his endeavor, and then they should all flee, save for him and the pilot (and Noah and his grandmother, both of whom refuse to leave).

That endeavor is the construction of the golem — "Sometimes it takes monsters to stop monsters," Jacob tells Noah — and, at the climax, the giant made of mud and earth that the old man literally prayed himself to death to create rises to defend the town and its people from the invaders.

There's little in terms of surprises to the story, which moves swiftly through its domino-like plot, but its folkloric origins lend themselves to this form of straightforward retelling. It's probably the best writing I've seen from Niles, who tends to have really great, really inspired ideas for horror stories, but whose execution sometimes falls short.

It is, as always with comics, the art that makes or breaks a script, however, and this is a really, truly beautiful book.Wachter works in black and white, appropriate to both the era and the character's silent movie mass-media debut (which proved inspirational to more popular still works, like the Frankenstein films). The choice also gives the book a more classical feel, and keeps the often quite graphic violence from getting too tactile and threatening to overwhelm the story; here blood is ink-black paint, not something red and vital.

You can see the golem in color on the cover. Wachter's golem is obviously a huge one, crafted with urgency by many hands, rather than by a sculptor with concerns or aesthetics or realism. When it rolls off its back to set about its mission, it takes the ground it had started to meld with up in big chunks. Its face is blank and expressionless, two eyes in round head atop a rough, man-shaped body. It's a created thing, not a person, with a task to preform rather than a life to live.

This "tale of the golem," a novella that amounts to little more than Wachter's dramatization of an updated version of an old story, reads as it should, as a legend of the time it's set in, one with important consequences for all involved, but not something that changes the course of the war, the world that's waging it or all of the people affected by it. Unless, of course, you hear about it, and are inclined to take its message about the importance and power of faith to heart.

It is also, of course, still a comic book about a monster fighting Nazis, some 80 or so pages of gorgeous artwork and a stirring appearance by a folkloric creature with a special place in American comics. Something for everyone then.