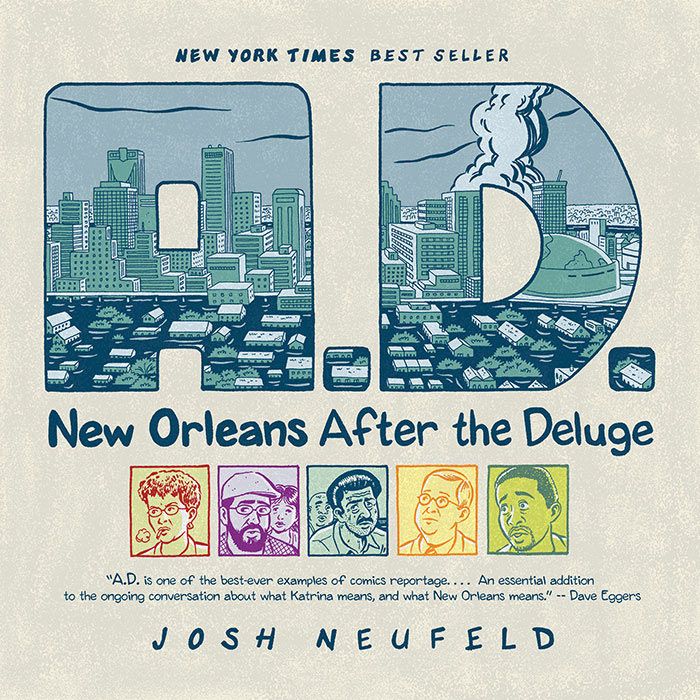

From the beginning of his time in comics, Josh Neufeld has been telling nonfiction stories. And since the release of "A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge" in 2009, Neufeld has built a reputation as one of the leading comics journalists, following "A.D." with "The Influencing Machine," a book examining the history and nature of the media written by Brooke Gladstone.

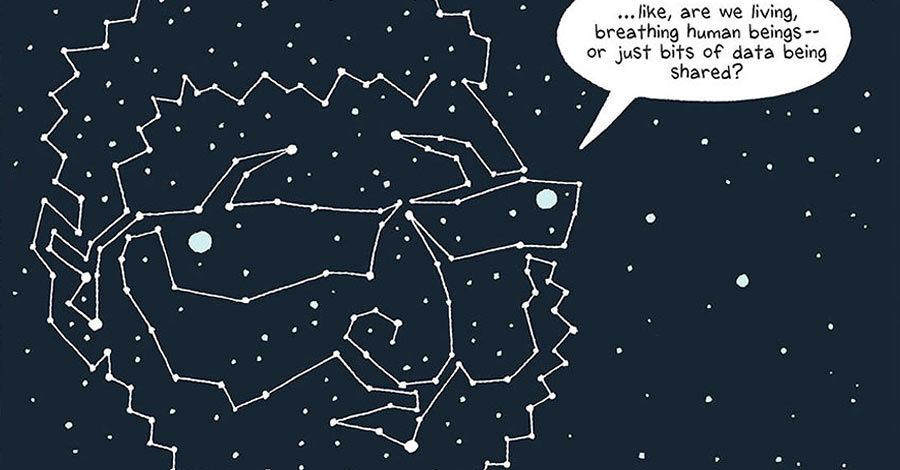

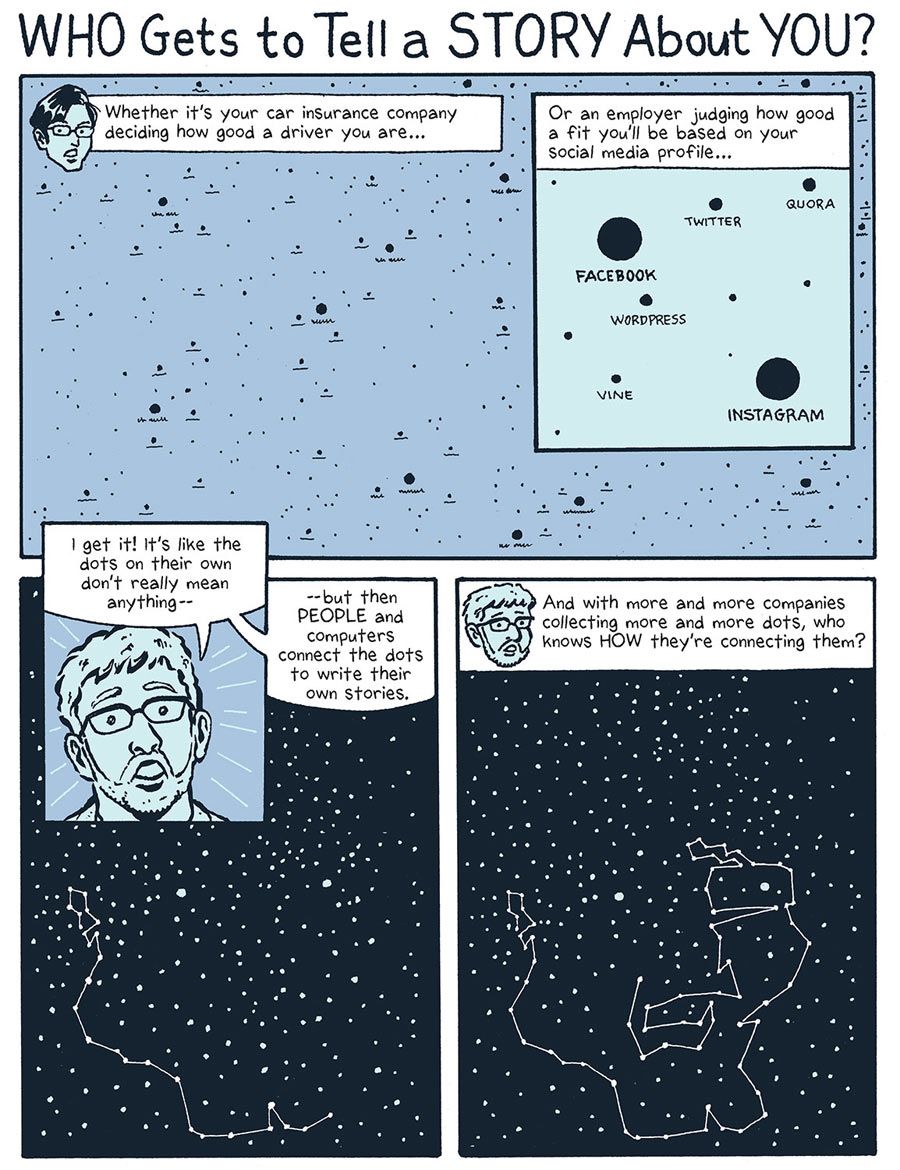

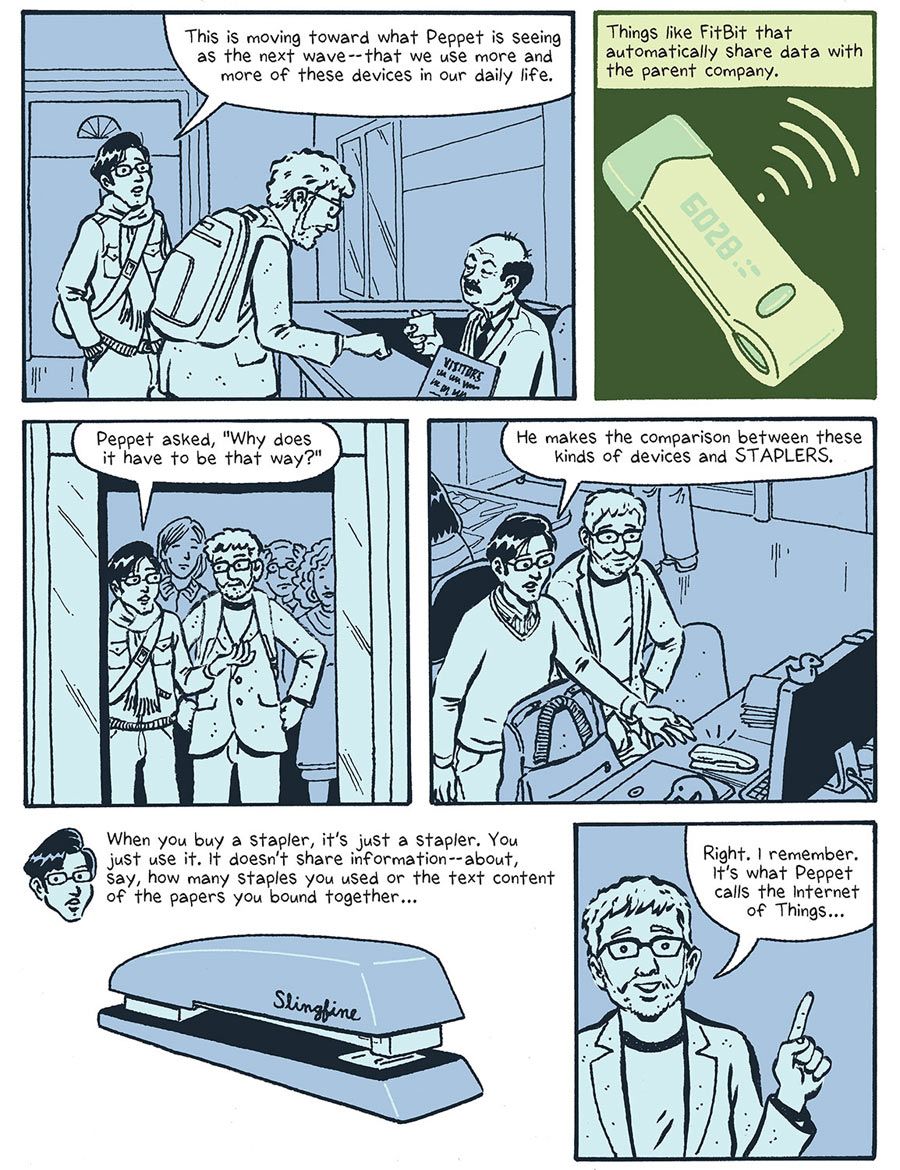

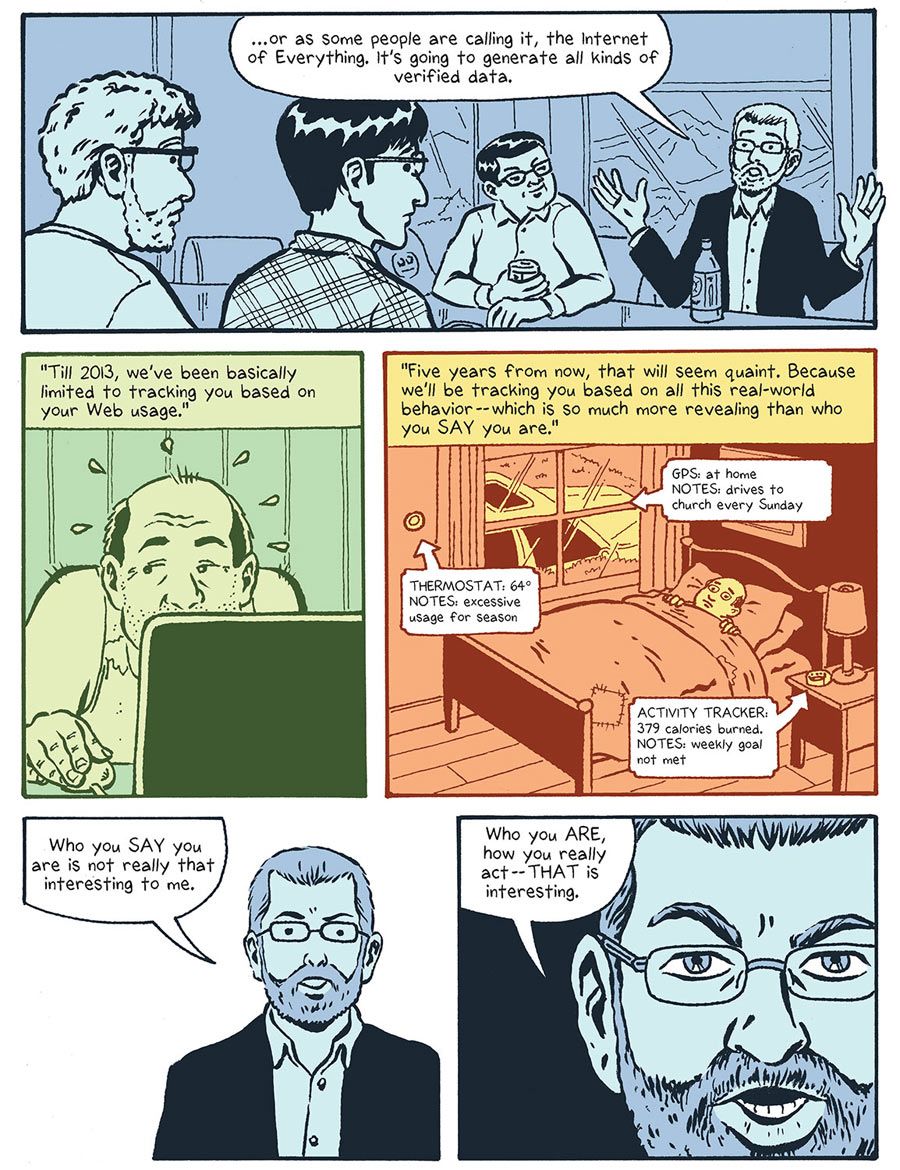

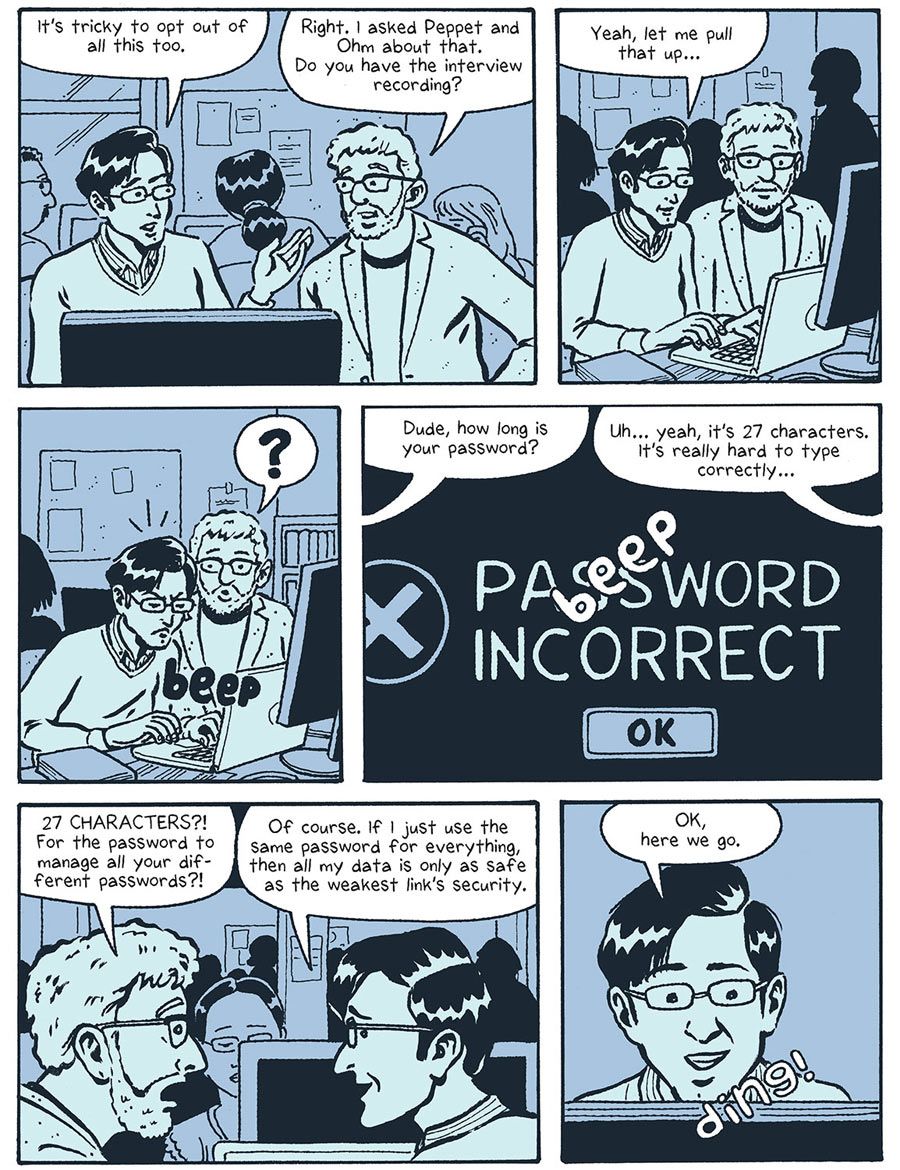

Most recently, Neufeld collaborated with Al Jazeera America journalist Michael Keller on "Terms of Service." The comic looks at the tenth anniversary of the release of Gmail, how big data has come to play such a significant role in our daily lives and what it might mean. In discussing the project with CBR News, we also talk about how his career has changed in recent years and the current state of comics journalism.

CBR News: Where did the idea for did "Terms of Service" come from?

Josh Neufeld: It began with Michael Keller. He's on staff at Al Jazeera America, on their multimedia team. What originally motivated him was the tenth anniversary of the release of Gmail. He was thinking back about how when Gmail was first released it was controversial for a lot of people -- privacy advocates, in particular -- because it scanned your personal emails for certain keywords to send you targeted advertising. But now, ten years later, the things that scared people about Gmail are things that we totally accept and don't even think about. When the Edward Snowden revelations came out about the NSA essentially bugging everybody, that was received with a shrug by most people. Michael thought that was a perfect analogy for how technology and privacy concerns have shifted so much in ten years. He thought that telling this story in comics form would be a great way to go. He knew my work in journalism and comics, and we had a friend in common, so he reached out to me. He had already done a ton of background reporting, but from the point I came on board, we reported the piece together, wrote the script together, and then I went off and drew it. He did all the back-end tech magic for making it work as a webcomic, as well as on all manner of mobile platforms.

Did you know much about big data before you started working on the comic?

I didn't know much about it from an expert point of view, but it's certainly something that I've been engaged with. As you can see in the piece, I use Foursquare and I check in at various places and give away all this data about my consumer habits. I use my phone for driving directions, which gives Apple and Google all this information about my movements in the real world. I'm on Facebook. For a time, I installed one of those trackers from Progressive Auto Insurance in my car that gave me a slight discount on my car insurance, but enabled Progressive to compile all this data about my driving habits. These were all technologies that I had engaged with, but hadn't thought too deeply about. I was really excited to be able to learn more about them.

Early on, I was pretty sure that the best way to tell this kind of story would be as a process piece, with Michael and me as characters in the story.

I was curious about that approach, because it presented the two of you meeting with experts to get background and then talk out these issues. Was that the idea from the beginning?

Michael's original take on it was more focused on himself and using that as a launching pad to talk to experts and "average" people. When I came on-board it just made sense for me to be a character as well. One of the Al Jazeera American editors suggested we frame it sort of like the Public Radio show "Radiolab," which features the two co-hosts debating issues in a similar manner. We thought that was a great idea and that it made perfect sense for this piece.

I really wanted to be involved in the writing end of it. I find it much more rewarding when I'm collaborating on comics, to not just illustrate the piece but to be heavily involved in the narrative structure and the writing as well as the art. Also, to add this element of two people who could bounce ideas off each other and have different perspectives on things really livened the potential for this piece -- which could have been just talking heads. I really dislike comics that take that approach. I feel like they're not really utilizing the form as effectively as it can be used. Personally, I think comics work best when they tell stories through action and dialogue rather than through people just telling you what to think or really dry "telling, not showing."

The addition of two characters who may have differing perspectives gives the story much more dramatic potential. It just so happens that we really do have very different perspectives on privacy and technology, and that really helped as we were crafting the piece. It was fun to get into the different ways that we look at the world. It was a really positive collaboration.

I was fascinated to read a lot of this background about Gmail and these debates, which felt quaint. I mean, I e-mailed you from a Gmail account. Companies like Google and Facebook and others define privacy very differently than anyone did 10-15 years ago and have really reshaped what the word means.

I think that's what's so amazing about some of these companies: their ability to anticipate future realities. They say, "Can we capture this data -- all of it?" We say, "Sure," because we don't see how that could possibly be useful -- or harmful. Then, two years later, you're being tracked in all sorts of ways, and your information is being used in all sorts of ways. Through working on the piece, I learned a lot about the dangers of it and the inequities in tradeoffs, but I'm not going cold turkey. I feel like I get something from these services like Facebook, Soursquare, Netflix, Instagram, Twitter, etc. There is some kind of reciprocity going on that makes it still worthwhile to me.

There was an article in "The Onion" years ago about how their social media initiatives had been a huge success because they used to spend time and money tracking people, but now they just let people give them the information.

That's a perfect example of a story that would be an "Onion" piece years ago, and now there's nothing satirical about it at all. It's completely true.

We first talked years ago, when "A.D." came out; your career has changed since that book. Not that you weren't making nonfiction comics before, but the book hit at the right time, was very good, and you've been recognized and embraced by the journalism community in a way that cartoonists weren't before.

Excepting Joe Sacco, of course, He should always be mentioned.

But yeah, I've been in the right place at the right time. In the last five years, the acceptance of journalism in comics format, or vice-versa, comics in the journalism arena, has really changed. In 2012, I won that Knight-Wallace Fellowship in Journalism, which I doubt would have been possible a few years before that, just in terms of the institution's ability to appreciate comics as a legitimate journalism platform. That coincided with the fact that journalism as an industry is collapsing and organizations are desperately searching for ways to salvage it. The field is a lot more open to other ways of crafting and presenting journalism.

So events have definitely gone my way recently, but I think I do what I do in a competent way. I may not be the best journalist, I may not be the best cartoonist, but I guess I'm able to combine the two in a way that feels satisfying to people. I've been invited to journalism conferences, and have been getting exposure in mainstream outlets, and reaching people who don't normally read comics as "fanboys," but read them when they overlap with their own natural interests. I feel really fortunate that things have broken my way -- and hopefully they'll continue to do so!

Following "A.D." with "The Influencing Machine" I'm sure helped to get your name out there and get your work in front of a lot of journalists and academics.

That was a factor, for sure. Working on "The Influencing Machine" also helped me just learn a lot more about the field that I'm in. Working on that book for two years was like going to grad school for journalism. Also, I have to say that the whole reason I was so enthusiastic about doing "A.D." way back in 2007 was not only that I had this personal connection with the region from having been a volunteer with the Red Cross, but I was looking for a way to get out of the autobio field. I was feeling very stagnant within that, and a little bit bored with telling these navel-gazing stories. I was much more excited about telling other people's stories. So in an ironic way, "A.D." was the perfect opportunity to shift career tracks.

You earlier said something that Joe Sacco has said repeatedly, that he's not the best journalist, he's not the best writer, but he can do both really well.

I take issue with him saying he's not the best, because I think he is one of the best cartoonists out there, period. It's messed up. It's like if Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster had not only invented Superman, but then created the best Superman stories, so that nobody who ever followed them would be able to compete -- that's sort of the situation I feel like with Sacco. He not only popularized the form of comics journalism, but he did it at such a high level that no one will ever be able to match the quality of his work. It's a little bit depressing for the rest of us. I'm not going to lie. [Laughs]

The key is to find a different approach, to find your own approach.

Exactly. And that is a really interesting thing about comics journalism, is it really is such an undefined form that everybody who does it practices it slightly differently. Some of us follow different rules than others in terms of what we allow and accept. I don't think it's ever erupted into a hot debate, but we're talking about more than just aesthetics. It's more like ethics -- about what's acceptable within the parameters of so-called"comics journalism," as opposed to, say, "creative nonfiction." It's a spectrum.

What's an example of this?

There are some people who are so strict that they'll only draw scenes that they personally have witnessed themselves. You can be so strict in your definition of what you're "allowed" to portray that I think it really limits your ability to use the comics form effectively. This is something I thought a lot about when I was at a journalism conference earlier this year. Within the normal print journalism community, there's a spectrum of different types of journalism. From what's considered the "gold standard" of the "New York Times" or "The New Yorker," where everything is primary sources, fact checked; ranging to the new journalists of the 1960s and 1970s who used much more of the techniques of creative writing to craft their stories. But when you read their pieces, you understood that you were learning about this thing through a very specific filter.

I think comics, by virtue of the medium, you're given a little more leeway for portraying things that may not exactly have happened that way or that, you weren't there to witness, or that you're recreating. You're allowed things within that mode that you would not be allowed on say, "60 Minutes," or an NPR radio piece. I think finding that comfort zone, ethically, within those parameters, which are still so ill-defined, is one of the challenges for comics journalists.

It can be really limiting, as you point out, but given that comics are by definition subjective, it's easy to understand why some people would be incredibly strict.

I was having a debate recently with somebody about Derf's "My Friend Dahmer." I think it's a really amazing book and it's told in an honest and non-judgmental way. This person was questioning the legitimacy of the book as a real resource about Jeffrey Dahmer because of Derf's art style, which is so exaggerated. I was saying, "Look, you need to get past your prejudices about what you accept as 'serious' artwork. If you look at the book in its totality, it is clearly a well-researched, honest, and 'objective' account of that period -- Dahmer's high school career -- as you could probably get." "Get over yourself," was my basic message. That person tripped over this medium of comics, and the art style overwhelmed his ability to appreciate the merits of the rest of the book.

I've spoken at a lot of high schools and colleges about "A.D.," and it's often not until I do my slideshow presentation and show them photos of the actual people who were the characters in "A.D." that it clicks for some of the students that they're real people's real stories. Even though I state it throughout the book, because it's in the comics form and because my style is sort of cartoony, I guess, they just automatically assume that the book is fiction. No. It's real. It happened. All the quotes people are saying are actual quotes that they said. The comics form a hurdle for some people.

That's an even bigger question beyond just journalism, the question of style and what's allowed or will work. This idea that a "realistic" story must have a "realistic" style.

What the term "realistic style" even means is such a vague term. "Maus" is a perfect example. One of the greatest works of memoir about the Holocaust, and yet it's told with this conceit of talking mice and talking cats. That took a lot of time for people to get past, but now it's a completely accepted work of art. A Pulitzer Prize-winning work of art. I love that. Because of my own art style, I'm limited in my ability to do likenesses of people or render the world in an overly detailed fashion. I love that comics give me the freedom to play around with those means of representation and yet still tell a true story. So for me, comics journalism is always that combination of journalism and art. I really think of myself as an artist as much as a journalist, and I want to flex those creative muscles and be as inventive as I can -- and yet also tell true stories. That's the conflict that I have within my own storytelling methods -- but I wouldn't have it any other way.

What else are you working on right now?

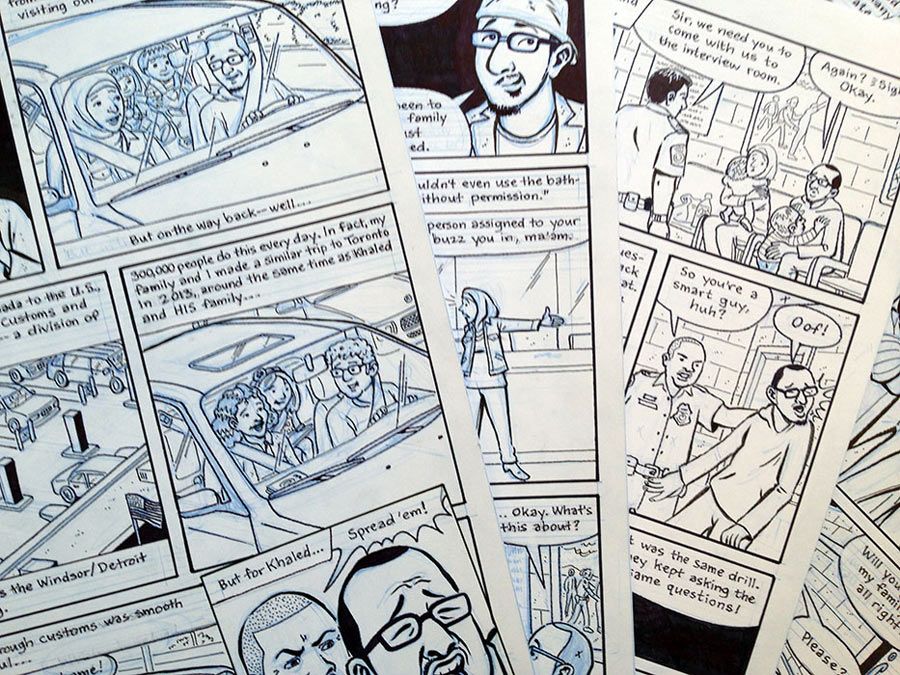

I'm working on a piece for Medium, for The Nib, about some Muslim Americans who were stopped at the border of Canada and the United States on the way back from a wedding, and were detained for eight hours and put through really harsh questioning -- all for no reason at all other than that they were Muslim. I'm doing a piece about that incident, focusing on one guy's experience. I was instigated to do the piece after hearing the story on the radio and thinking how comics could really bring home the realities of mistreatment they went through. So I found this guy, reported what he personally went through, wrote the piece, and am now finishing up the artwork on it.

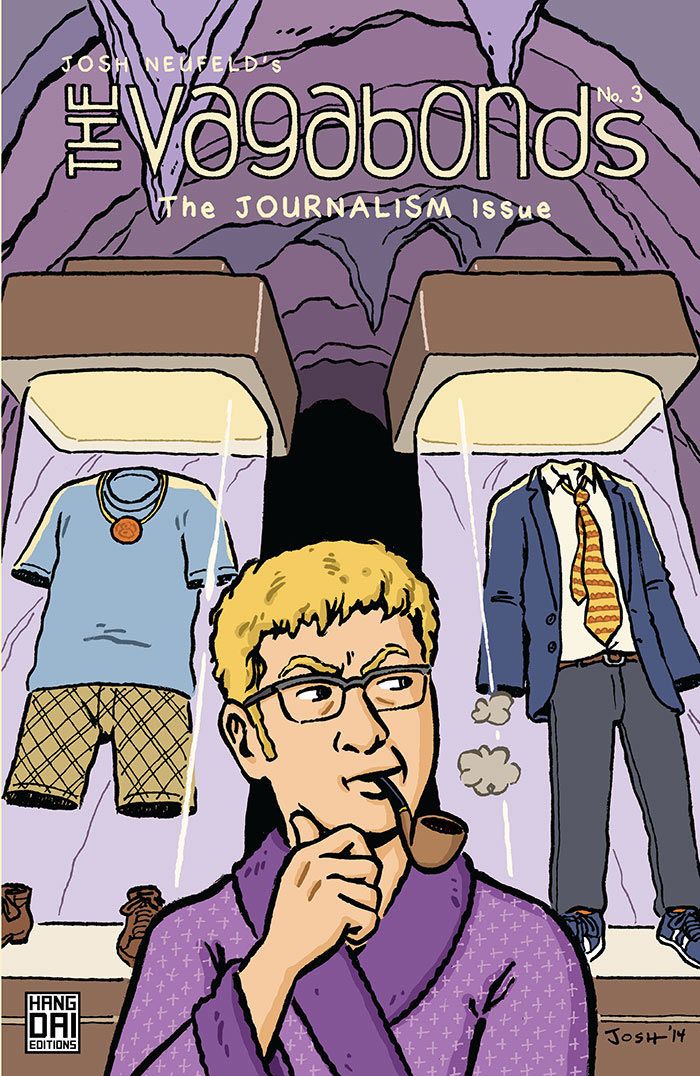

Then there's a thing I'm doing with the Gates Foundation, about Jonas Salk and the polio vaccine, that's more of a public service announcement piece. I have a piece in the works about the Koch Brothers. I'm also assembling a new issue of "Vagabonds," my solo comics series, which is published by Hang Dai Editions. A fourth issue will be out in time for the MoCCA Festival in the spring. I've got a couple things in the hopper, but no super-long projects lined up right now. That's the way I've been trying to play it since coming back from the journalism fellowship. I'm not really focusing on book-length projects right now because that sucked all the air out of my life for about four years. I'm trying to do more comics journalism pieces for mainstream outlets, clients like the Al Jazeera America piece I just finished. Things have been going pretty well in that area for the past year and a half.

Do you see yourself doing this for the time being?

I do really think of myself as comics journalist now. I like doing these kinds of stories, and I'm really excited by the potential of the form and the reception that it's getting. Ironically, it was interesting to do "Terms of Service" because it was one of my first journalistic pieces where I was back as a character in the story. One way I had differentiated myself from Joe Sacco was that in most of my journalism comics, I wasn't present in the way that he's so present in his pieces. Doing "Terms of Service" made me think now, maybe there's a way to come back in a character, as long as I'm a stand-in for the reader. In the piece that I'm doing for Medium, I'm more of a character as well. Maybe this is becoming something I'm more comfortable with.

In any case, I'm excited about the potential that the form has right now, and that it appears there are actual ways to make a living as a journalist and as a cartoonist!

Do you have any thoughts or advice for people interested in the field?

My advice, first of all, would be to really learn about what's required to be a responsible journalist. It can be a minefield. You have to be really careful about how you portray things, events, how you represent people that you've spoken with, etc. Additionally, you need to think about imposing your own point of view onto a story and leading readers to a conclusion, versus letting them draw their own conclusions. There are a lot of different factors to think about, and those start long before you ever start drawing anything -- it's when you report the piece and when you structure and write it. I'm a proponent of doing a lot of research, figuring out your story, writing a full script, and only then starting to draw the piece. I think particularly when it comes to comics journalism you need to have all your ducks lined up. I wouldn't say it's something you can just jump into if you think it's a cool form and you want to "try your hand at it." You're telling other people's stories and you have a responsibility to be respectful to them and their experiences.

But, when it comes to comics journalism, in terms of art style, I feel like it's totally wide open -- no set rules.