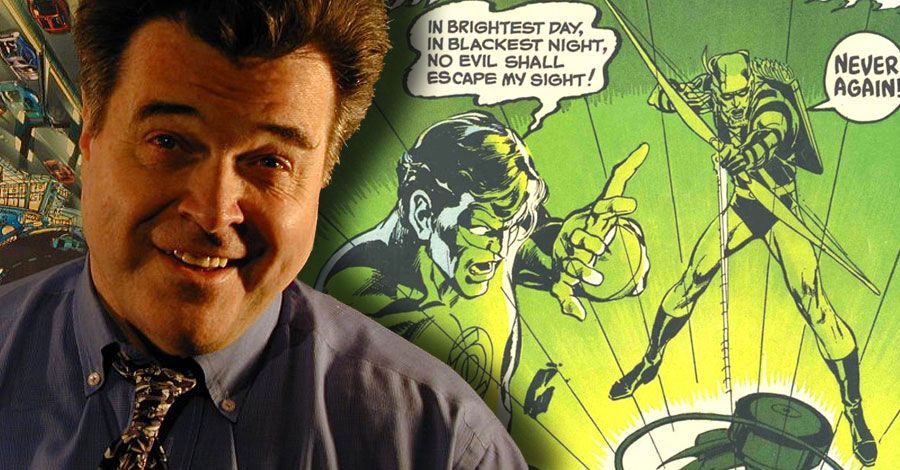

Neal Adams turned 75 last month.

There are few cartoonists alive who are more acclaimed, more influential, and more beloved than Adams, who was responsible for the co-creation of Ra's Al Ghul and Talia, Man-Bat, revitalizing the Joker, and returning the dark and moody tone to Batman's adventures after the end of the Adam West TV show. He and Denny O'Neill had a run on "Green Lantern/Green Arrow" that holds influence over the characters to this day. Adams participated in Marvel Comics' iconic Kree/Skrull war storyline, and co-wrote and pencilled "Superman vs Muhammad Ali."

RELATED: When Muhammad Ali & Superman Saved the World

But despite that impressive resume, what has made Adams so loved by fans and pros alike is the work he's done for the comics industry. At Continuity Studios, he's hired and mentored dozens of creators, despite taking a decades-long sabbatical from comic boom work, and continues to do so to this day. He was at the forefront of the movement that pushed DC to return artwork to artists and to pay royalties. He was one of the people pushing for credit and a financial settlement with Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster.

Adams is an opinionated man. I'm sure most art historians would be tempted to strangle him as he details why he believes pre-modern art sucks, but to listen to him talk about the time we're living in, about how we'll never know what it means to be white and the importance of diversity, and more, he sounds like someone half his age or less. As I learned while spending a day with him at Continuity Studios headquarters, Adams has long been ahead of the curve.

CBR News: What's a typical day like here at Continuity Studios?

Neal Adams: If it's a typical day, it's a boring day, because we do new things all the time. You've seen the studio. We have editing rooms. We do motion capture in the next room. We had the 15th floor here until the advertising agencies caught wind of us and realized that we were making too much money. [Laughs] They realized that they could do production in the agency where they could control it themselves, which was rough. You may not know it, but I disappeared for two or three decades.

You weren't really drawing comics from the late '70s into this century.

I drew covers, and we were publishing for a period of time. I was doing a lot of advertising. I was sort of waiting for the industry to catch up to me. The thing about advertising is that you make more money. You can put kids through college so they don't come out with loans. My kids don't and my grandkids don't, and advertising paid for that. Comic books probably wouldn't have. It was a good place to go. You may or may not think so and I wouldn't expect anybody to think so. When I was doing comic books back in the day, in many ways I was ahead of everybody. We had come through a very bad time in comics where the comics code was established and the artists that were left were steady, but were not too creative. Your Wally Woods and your Jack Davises and your Al Williamsons and Reed Crandalls and all those people who used to work for EC were basically thrown out into the streets. Al Williamson became a ghost for different comic strip artists. He was the inheritor of the Alex Raymond school, and he was the logical inheritor of the Flash Gordon comic strips, and he did not get them because people making decisions for those things were stupid. And remain stupid. But it doesn't matter anymore because nobody cares about comic strips.

Wally Wood was doing spot illustrations. Jack Davis was doing advertising. Reed Crandall became a night watchman. He was semi-rescued from that by Al Williamson when Warren began to publish, and he started to do comic book stories again. You had good and bad people left over, but as a result you had no new people in the comic book business. There was nobody either five years my junior or five years my senior in the industry. There are people my age who got into it later, like Jim Steranko and Dennis O'Neill -- but people my age were not in comics. I came into this business that older guys who were sad and depressed and assumed that the industry was going to be out of business in a year.

Things were that bad when you started out?

I had turned 18 and I was looking for work, and they turned me away. Joe Simon was too nice to allow me to ruin my life doing comic books. He felt it would ruin my life. It was sincere. Jack Kirby didn't know, Joe did it on his own. The people at Archie felt sorry for me, so I did Archie Joke Pages, but then I did advertising at Johnstone and Cushing, I did illustration -- and I was paid much more than all the guys who were doing comic books were. I was getting $200, $300 a page, sometimes $500 a page, while I was paid $32.50 a page for writing, penciling and inking an Archie page. I did other stuff. I did design work. I wrote advertising comic magazines -- one for the National Guard, one for Tintex, a clothing dye, several others. I honed my writing skills doing that. I had a syndicated strip before I was 20 years old.

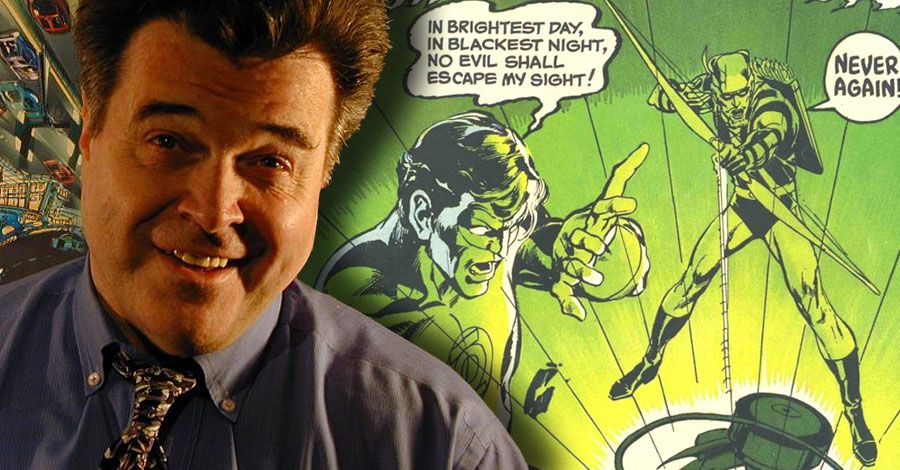

This was "Ben Casey."

I did that for three and a half years. In that syndicated strip, I was competing with Stan Drake, Dan Barry and the best comic strip guys in the business. For three and a half years I would check the dailies every day to see who was better. I busted my ass. And while I was doing that, I did advertising work because that strip didn't pay all that well. I worked seven days a week, 15 hours a day, and I loved it. I just loved it.

So when I fell back into comic books when the strip ended by mutual consent, it was as if I had fallen out of the sky. Who is this guy? He knows about color separations, he knows about Zip-A-Tones, he knows about halftone prints, he knows about textures, he knows about the various colors we get for our printing. He knows that DC Comics gets 32 colors and Marvel gets 64 colors. And he doesn't want to be a publisher, he just wants to do this stuff. One may easily think that I did comics for a long time, but starting with the I guess "Elongated Man" and ending with "Superman vs Muhammad Ali," that was the beginning and end of my comic book career. From that point on I did advertising.

Now, I have come back to comic books. All those eggs that I laid, all those things that I tried to introduce, all those concepts that I fought with the companies about -- in a nice way, in a friendly way -- all those things finally happened. The artwork got returned. I convinced DC that they ought to pay royalties. That changed the face of the industry. I changed separations. [My daughter] Kris, who you know, was the first person to go to Canada to Quebecor. Now suddenly we could get better printing. Kris went up there and made the deals and we made product and gave it to DC and Marvel and Valiant and said, "You guys want to do this? Here's their card." We didn't take a commission, we just said here's the guy to call. We created a new look for the industry. More young artists graduated and came into an industry that was welcoming them and that was looking for better artists. Now competition was better. Now I'm swimming in a pool of people who are equal to me -- if not superior.

Back in the day, really honestly, there was no competition. There was Joe Kubert, who was a legend. There was Russ Heath, who's fantastic. There was Mort Drucker, who's the best caricaturist in the world. You've got somebody like Will Eisner who changed the business, who believed in the greatness of comics. There were some other people like Barry Smith and Bernie Wrightson, but not many. They threw away the best artists that they had. Alex Toth went to California to work in cartoons and he was brilliant. Now we have more of an adult industry with skilled artisans, writers who write in television and film as well as comic books, we have a tremendously competitive industry that I'm very grateful to be in. I'm having a great time.

Has most of the work that Continuity does is advertising? What exactly do you do here?

There are people in the world who think that I'm smart. A guy who runs an amusement park ride design company might call and say, we're trying for licenses and we'd like a comic book guy who can illustrate and do these designs and then fulfill them. Which is what happened. Then the same guy asks, do you know anything about amusement park rides? I say, I grew up in Coney Island and I studied engineering. So we bounce some ideas back and forth and I started to design rides. I designed the "Terminator" T2 3-D ride. I designed much of the Spider-Man ride. In the last year and a half I designed seven rides meant for Indonesia. When you say design a ride, you either do the initial design, the creation of the ride, and then you possibly do the delineation of the various ways it's going to be done. Then they do the engineering, which is a totally different thing.

We did comic books for Wendy's. Classic stories like "The Snake and the Elephant," "20,000 Leagues Under the Sea," "Peter Pan." They were looking for somebody who could do 3-D. I said what if we could do comic books that were in color and they weren't in 3-D unless you put on the glasses. They printed 6 million copies of each and gave them out at Wendy's. We didn't get a royalty for that, but we got paid very well. There tend to be lots of different kinds of projects that come through the studio. Sometimes I direct stuff. Sometimes we do CGI. We do a variety of stuff. The advice you give to people is don't put a lot of variety in your portfolio. You want your portfolio to be one specific thing because that way you'll get that work. We go against that. Everybody in advertising knows that I do preproduction, and everybody in comics knows that I do comics. That's what they already know. I don't have to sell that. Other people come to me and ask, can you do this or can you do that?

Someone like Marvel Comics will ask, can you do a motion comic?

Marvel wanted to do a motion comic. We came to them and said, can we show you what we can do? We showed them and they fell off their chairs. We had done what amounts to motion comics as animatics for advertising agencies for 30 years. Some of them much more sophisticated than others. We showed them this and they asked us if we could do a sample of a Frank Miller "Wolverine" and so we did it and they hired us to do "X-Men." For what it was, it was stunning. We discovered they had been doing the same thing at Marvel for two years and coming up with shit, so they hired us to do it. Now during that time other companies began to open up and they went for the second book to a company in Canada. Well, the second book was really not very good. They had another company do "Thor," which had some really good pieces, but they couldn't carry through for the whole thing.

Nobody has found a vehicle to properly do it for a commercial project because they're not focused on it. If Marvel can make money doing comic books and participating in the movies that costs hundreds of millions of dollars and they can make hundreds of millions of dollars and then they can do animated specials for $3 million or $4 million and sell $10 million worth of product, why do a motion comic? You have to build that market. Nobody so far is doing that. There are now various people around the world and in the United States who are now contemplating what we've done from the point of view of maybe trying to move this forward.

Are you often thinking along those lines, what's next, let's try something new?

The difficulty that I have is that I don't think in the present day. I think in the future. Most of the things that I do that I care about are made for the future. Today I'm doing a "Harley Quinn" special. At the same time, I'm bidding on some motion-capture animatics for the world market. That's what I'm interested in. I do my "Harley Quinn" book because I have the skills. DC wants me to do something big. That doesn't make any sense to a certain extent. What you want to do is take Neal Adams who saved the "X-Men" from cancellation, who saved "Green Lantern" from cancellation, who saved "Batman" from cancellation, put him on a crappy low-selling title and make it work. That's what I would do. But they think, we're paying him this much money so we'll put him on "Harley Quinn," which is selling well and maybe it'll sell more. That's fine.

Continuity has changed a lot over the years, but fans might remember when you used to publish comics. What was the original plan for Continuity Comics?

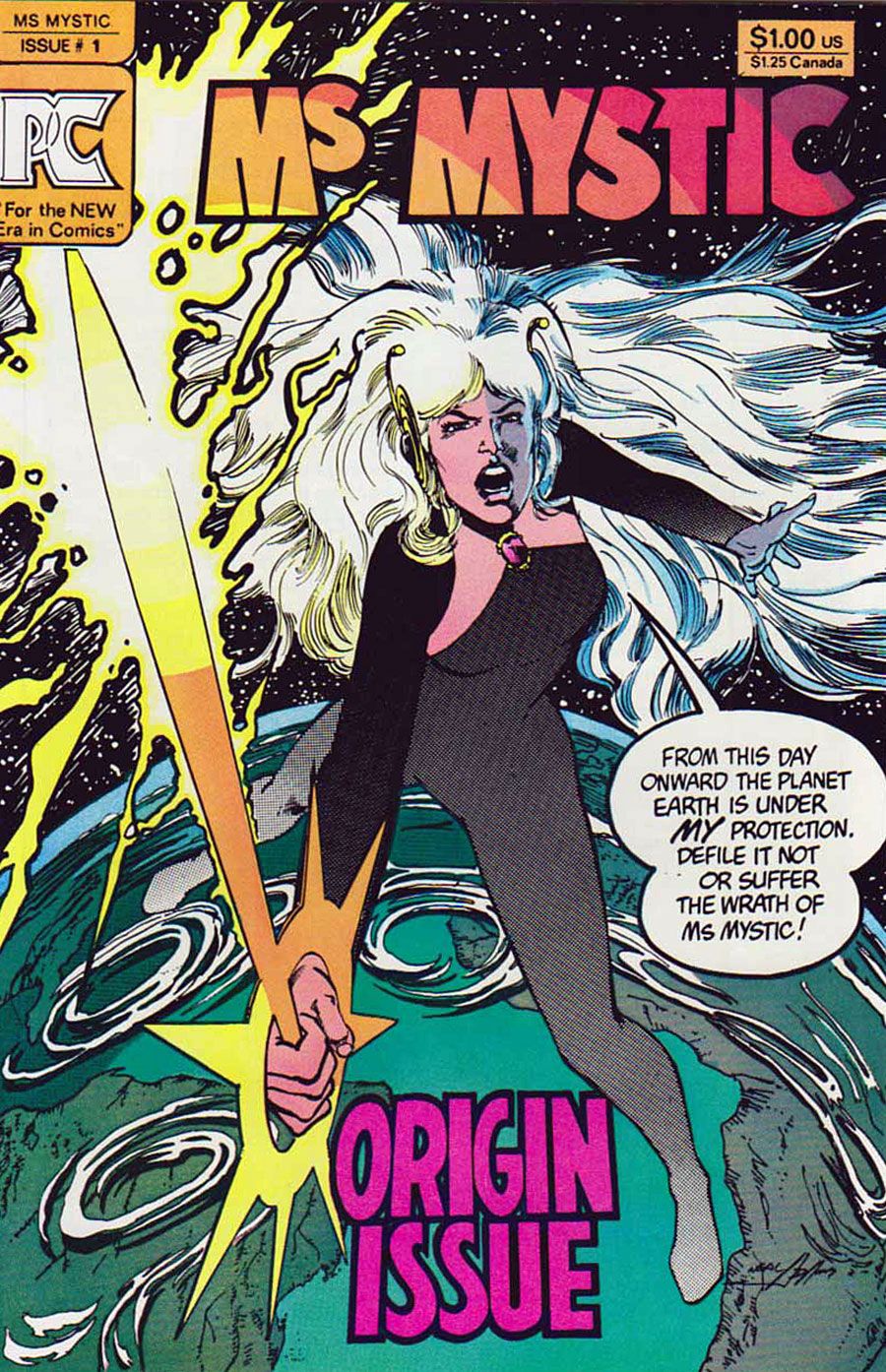

To make back my $62,000. I had done "Ms. Mystic" for Pacific Comics, and at that time we decided that we would do an anthology magazine called "Echo of Futurepast." I bought licenses for strips from overseas, I hired people in America to do strips, put money I made in advertising into it. We published maybe 10 magazines. There were a lot of good things in there. The dealers hated the book because it cost $2.95. [Laughs] At a certain point Pacific Comics went under and they owed me $62,000. I thought, how do I make back that, maybe if I publish the stuff that I prepared myself? That made me a publisher -- to try to make back the money that I had lost doing that stuff. It's an awfully mundane and terrible reason to publish, I fully admit. We published sporadically until we got to "Deathwatch 2000," and that did great. At that point, we hit that moment in the history of comic books where we had this glut. We lost 1,500 stores that year. I stopped and backed away. On the other hand, we were so successful with "Deathwatch 2000" that we cleared up any debt that we had, which was fantastic.

Earlier when she gave me the tour, Kris [Adams, Neal's daughter] mentioned that this room used to be the conference room, and you've taken it over for your studio, which is emblematic of how your focus has changed in recent years.

I've always been a freelancer. I never feel comfortable having an office. I feel more comfortable camping out somewhere. As long as there's a table. That's all I've ever needed.

Have you been exploring a return to publishing?

I'd be insane not to.

You mentioned a few titles, but the one most people probably remember is "Bucky O'Hare."

[Adams sings some of the theme song] We're trying to do "Bucky O'Hare" as a feature. We've done animation for "Bucky O'Hare" ourselves. If our finances get together and if somebody doesn't buy it, we might do it ourselves. Bucky would make a great feature. It's a really good property.

I remember the TV show.

Exactly. The stories were good. I would make the writers write an hour show and then edit it down to half an hour so it had a real story, because animation moves fast. I wanted the people to see a story happen that has events and results. Not "Fred wants to find a rock." All those shows were appreciated by the audience. They misallocated the toys, and because Hasbro dropped the ball, the show was canceled. I mean, everybody was making money off "Bucky O'Hare" except for the toy company. I would go to Toys R Us and every Bucky O'Hare is sold, every Dead Eye Duck is sold, every robot is sold, every Green Rabbit, but the secondary characters just sat there. They said they had millions out there. It was a disaster. The licensing people were suing each other. I'm in the middle saying this is a great product. I just didn't believe it. We made so much money on that. Unbelievable.

Do you have a favorite Continuity character?

Not really. They're all naked men with lines drawn on their bodies, aren't they?

Some are naked women with lines drawn on them.

True, some are naked women with lines drawn on their bodies, and then you color different areas. I'm asked this at comic book conventions all the time. What I generally say is that Superman is the creator of the industry. He is the most powerful comic book superhero, and even if people create characters who are as powerful, he's still the most powerful. Because he's an alien and he was created by two Jewish kids in Cleveland, Ohio, and he started an industry. As a response to that, the publishers said do more of those. As a result, Bill Finger and Bob Kane created Batman, who was totally derivative. Nothing wrong with that. There's nothing new under sun, at least that's what they tell me. They created a character who wasn't super in any way. He just is somebody who is seeking revenge for his parents' death and he is lucky enough to be perhaps the greatest detective in the world and perhaps the greatest athlete in the world by training.

Between them lie all the characters in the comic book business. Those are the two bookends that hold the business together. I like them both. I like everything in between. I like Captain America because I liked Captain America when I was younger. I loved the old Captain Marvel, and I do not understand why Marvel Comics does not turn over the rights to Captain Marvel to DC Comics so I can have a Captain Marvel comic book.

You don't call him "Shazam"?

[Adams' expression cannot be summed up succinctly]

Stan Lee stole it out from under DC. Just out of courtesy they should return it. But businessmen don't do things like that, and so they suck. Look, lawyers suck and businessmen suck. I'm sorry. As much as I'm a businessman, and I have to be a businessman, there are moments when I suck. I will have a thought and go, "That really sucks. Neal, you're an asshole, don't think like that." But businessmen think that way. Nothing is gained by not being kind and courteous. Marvel gets nothing out of Captain Marvel that they couldn't out of "Fred" or "Joe." Why don't they return it to DC so at least DC can make up for the crap they gave to Fawcett and turn out a Captain Marvel comic book? I'd like it. I love Captain Marvel. I'd love to see a Captain Marvel movie. Wouldn't that be great?

CBR's interview with Neal Adams concludes later this week.