In "Nameless" #2 by Grant Morrison and Chris Burnham, Nameless joins his new teammates in outer space. Morrison combines his usual interests in mysticism and antiauthoritarian attitude with sci-fi horror plot twists and a potentially world-ending threat. "Nameless" #1 focuses heavily on the occult, but the second issue leans more towards space opera.

Nameless, the titular hero, continues to be a combination of magician, wise man and rebellious loner. His doomed romantic motivation is a cliche and his "gruff cowboy with a heart of gold and all the answers" persona is also a familiar stereotype, but Morrison manages to make the character feel new by giving Nameless scene-stealing dialogue like his request to use the "moon toilets."

While Nameless hasn't been given a lot of fleshing out, he can hold the spotlight. The same isn't true for the other characters. Morrison spares readers the usual character 'round-the-spaceship or roundtable introductions. Unfortunately, he doesn't have a better method, so other members of Serenity Base barely have a face or name attached to them by the end of the issue, and there's little reason to care about them. Morrison gives Sofia some panel time, but he doesn't do more than establishing her as an idealistic young girl who triggers Nameless' protective instincts.

The "crew of experts" cast of characters is a cliche, but Morrison is fully aware of this and even has characters break the fourth wall to say that they're "just like a film." The irony is amusing, but it's an inadequate consolation for thin characterization.

The plotting of "Nameless" #2 has the same kind of construction as the characters. It feels bizarre and original on the surface, but a quick analysis of the innards reveals that it's a bunch of familiar tropes mashed up. The round-table debriefing is composed of information dumps, but what Nameless has to share is so riveting that it doesn't have the usual retarding event on the suspense. The skeptic vs. believer argument comes up, but Morrison's heart doesn't seem to be in it and the debate lacks heat and tension. Burham and Fairbairn play up the horror with ominous camera angles and color choices when Nameless says his piece. They overdo it a bit, because he looks like he's raving inside an abattoir, but it works to prevent boredom during a scene that is otherwise talking heads and exposition.

The madwoman in a jail cell is like any other ticking time bomb. Burnham's pacing and transitions are excellent, so the progression of events still feels chilling despite its predictability. The near-inevitable betrayal of someone critical to the mission plays out the same way, getting its hooks into the reader despite how predictable it all is upon reflection. That's par for the course for horror; the sources of fear are never new, but there can be new paths to familiar destinations.

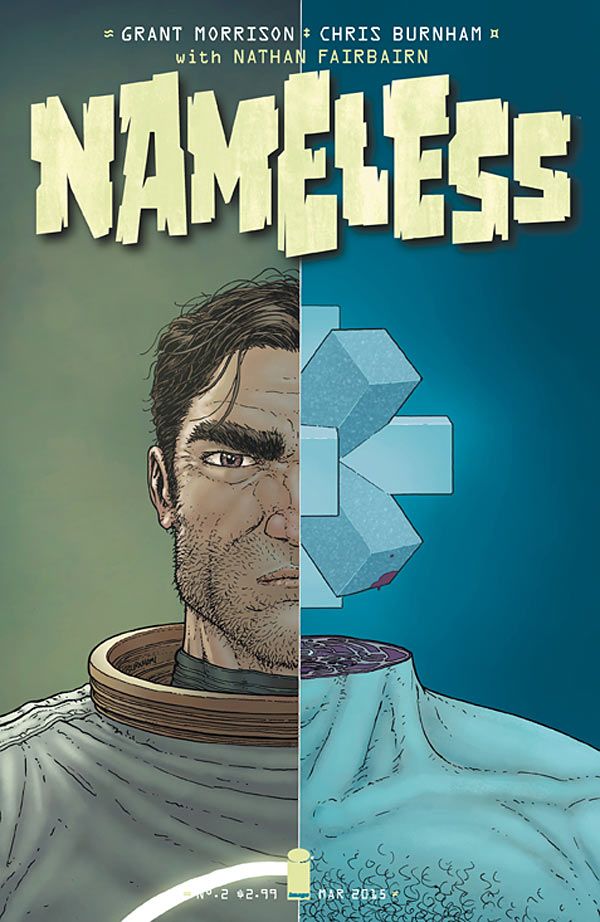

Burnham's art is not elegant or pretty, but he's got a distinctive style and his storytelling is very smooth. His visual pacing and imagery are crucial to the creepy effects, and his jittery, fuzzy line reinforces the anxiety and grittiness in the action. The panel composition where the panel shapes form tunnels and tubes is ingenious and fun. Fairbairn's color palette of cold neutrals and fluorescent red and blues isn't attractive but, in the context of the gruesome story, that's fine. He doesn't make full use of Burnham's detailed backgrounds by using monotone so much across many panels, but that doesn't interfere with the mood or action of "Nameless."

Strip away esotericism, and "Nameless" follows the usual space horror template. It's more style than substance currently, but the style is engrossing and unusual enough that "Nameless" is worth reading for the texture of Morrison and Burnham's world building and Nameless' dialogue.