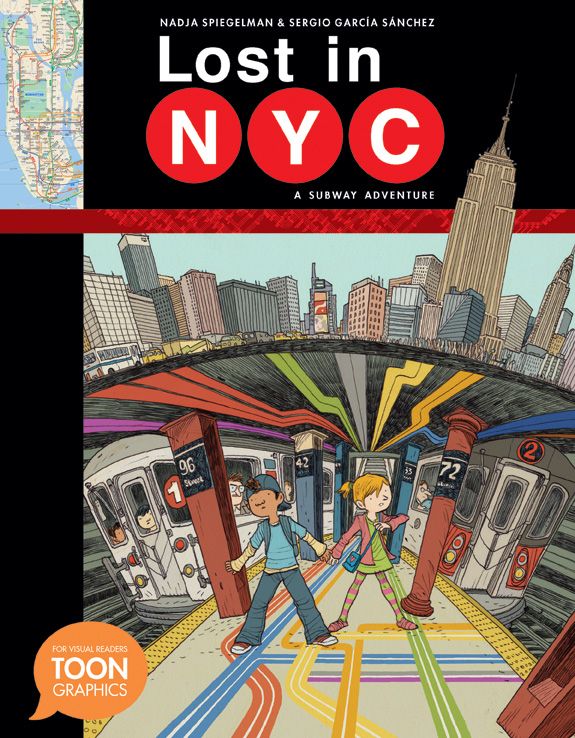

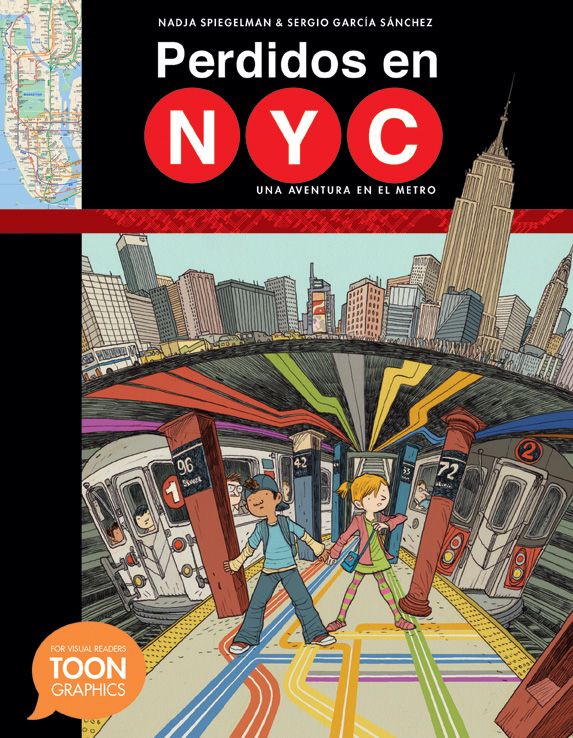

Nadja Spiegelman, daughter of "Maus" author Art Spiegelman, has one of the most famous names in comics. An Eisner-nominated writer in her own right, the younger Spiegelman is proving talent doesn't skip a generation. Her latest argument is "Lost in NYC," set for release from Toon Graphics on April 14 in both English and Spanish language editions. The new graphic novel is based in New York City's famous subway system and follows a child named Pablo as he gets separated from his schoolmates on a field trip.

The Paris-based author previously created two graphic novels for kids, "Zig and Wikki in Something Ate My Homework" and "Zig and Wikki in The Cow," both drawn by Trade Loeffler. The books demonstrate a playful approach but also Spiegelman's skill at finding ways to synthesize and incorporate information into a fictional narrative. For "Lost in NYC," Spiegelman collaborated with Spanish artist Sergio Garcia Sanchez who pushed her script in novel and experimental ways.

Spiegelman spoke with CBR News ahead of the book's release about how she settled on the story, her collaboration with Sanchez, what kind of research it took to properly capture the New York subway system -- and the comic she wasn't allowed to read as a child.

CBR News: On the surface it's a story about a lost child, but how would you describe "Lost in NYC?"

Nadja Spiegelman: It's difficult, because there are many layers to this book. It is foremost a unique visual experience, but I suppose if I meant to tell the plot, then it's about a new kid who gets lost during a field trip to the Empire State Building. First, he and the sweet girl who offers to be his partner get separated from the rest of the class and then -- after a fight -- from each other. Somewhere in that mayhem, he learns to master the madness of New York and make a real friend. It's also a non-fiction book filled with facts about the New York City subway system that reflects my own love for the city.

I grew up in New York and I felt, from a very young age, how much freedom and autonomy the city provides for a child. Then I recently moved to Paris and experienced how difficult it can be to navigate a system you've never encountered before. I suppose that, in a way, the helpful NYC veteran and the shaken new kid represent two halves of my own experiences.

I wound up with pages and pages of research as I was working on the book, and it was difficult to determine what of that I could make interesting and what was just going to slow the story down.

Did the book's layout, where pages provided in the back explain a lot of details and lay out additional information, help you determine what research to include in the story?

It's one of the wonderful things about the new Toon Graphics format, which the Toon Books imprint launched in the fall of 2014. All of them have pages of information in the back, even the books that are pure fiction. It opens up so many more possibilities, to be able to break some of the facts out from the story and have them in the back. I really love doing research, especially when I discover how much more there is to know about something, like the subway, that I already thought I knew well. I wound up with a lot of material, but I worked hard to make the information feel integrated throughout the book. I wanted readers to have their own voyages of discovery rather than having facts presented to them in big didactic blocks.

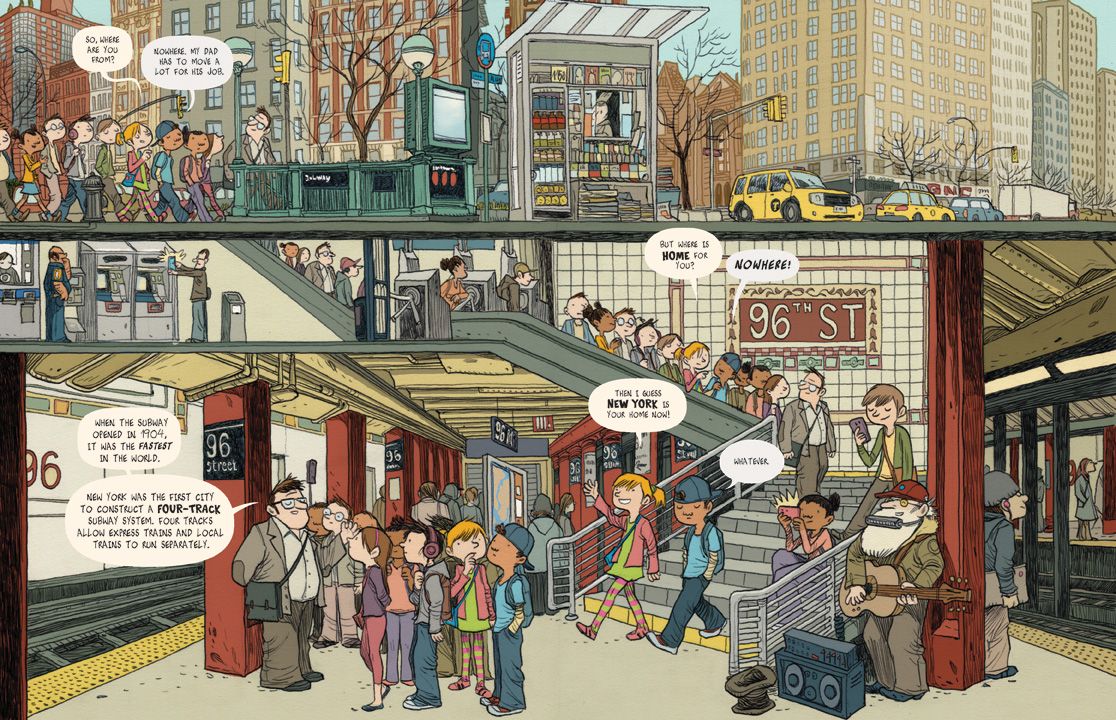

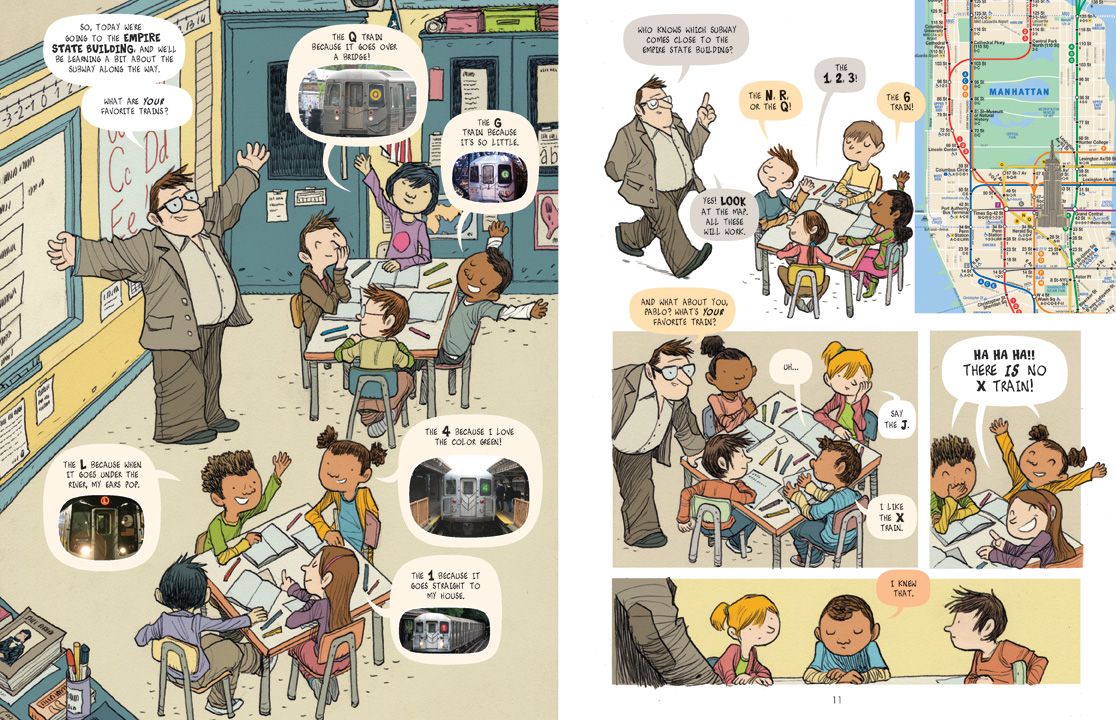

One of the fun things I learned was about the naming of the subway lines -- why some are letters and some are numbers, why they didn't simply name the lines in alphabetic order. It's difficult to make generalizations about the New York City subway system because it was, in the beginning, built as several independent, privately-owned systems that were later integrated into one. You can't say 'all the platforms are like this' or 'this is how they all work.' At some point, I found out that New York was the first city to have a four-track express track system. I found that really interesting so I started basing the story around that even though it's complex and not necessarily an immediately appealing piece of knowledge. [Laughs]

It's not an obvious story idea, but the class gets on one train and these two kids get on another and that sets the plot in motion in a way that works well.

Before doing the research, I thought that New York had this incredibly modern subway system but, in fact, New York was very late in building its underground subway. By the time that it did, in 1904, an underground subway wasn't particularly revolutionary, but New York did innovate with the first four-track system, allowing express trains to bypass local stations, and that made it among the fastest in the world at the time. So that ended up being a key component to the plot.

One of the most notable things in the book is Sergio's page layouts, which are incredible. How did the two of you work together and make that work?

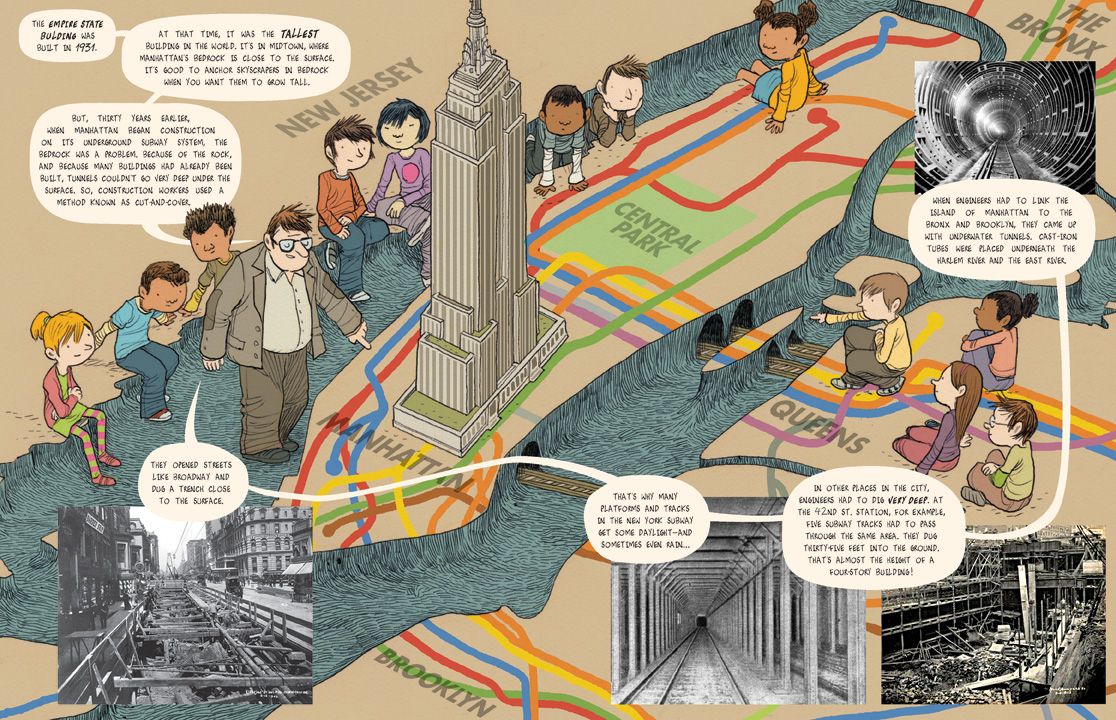

Sergio is just wildly imaginative. We wanted to work with him because he's really interested in all the ways you can stretch the form of comics. A lot of his work is very experimental, trying to push page layouts to the limit. Much of what's special about the book is the way that he drew it. His technical skills are extraordinary: there's nothing, no matter how complicated, that he can't visualize and draw. He can mix different perspectives into the same picture and make it look coherent; few artists can do that.

When I started doing the research, I came across some very beautiful cutaways of the city in architectural renderings and old photographs. I loved that view, where you can see all the different strata and layers, the city extending both above and below the sidewalk, and I knew that I wanted it to look like that. Then there are many variations and visual play that Sergio added in. For example, on the spread where the two characters are in the subway car together, they end up using the gutters between the panels as subway poles. All those small details are what make it a book worth poring over for hours.

Was there was a lot of back and forth to get the dialogue right and make sure the page flow worked?

There was a lot of back and forth, but it was a lot of fun. I first sent him a scenario that was more like a movie script, with dialogue and some stage directions. Then I worked with his sketches and his page layouts to rewrite the dialogue and make the story work around what he was doing. It feels so magical to be able to write a story and then see it come to life through somebody else's eyes, and it's really special to be able to do that with an artist who adds so much more when he's doing the actual layouts.

Sergio has a great approach to using space. Was part of your initial thinking trying to use space in this way?

Definitely. There was a book I loved to read with my mom when I was little, which showed the different events of well-known fairy tales charted out on a map. I loved that book. I loved the visual parallel between maps and narratives, and I wanted to try to recreate that experience. I had seen the books Sergio had done before, a few of which played with stories as maps, and I found them quite inspiring.

I actually wrote the story staring at a subway map. In its first conception, the story took place on a map at all times. There's one page that still looks like this, where you get to see the different paths that the class and then the two main characters took, but it quickly proved to be too complicated and too flat to sustain throughout the book.

There's a moment early on in the classroom where the teacher asks, "What's your favorite train?" and Pablo has no idea, so he just blurts out a letter. There is this feeling of, "Everyone knows this and you're new and have no idea what's going on," which I -- and I'm sure a lot of people -- can relate to.

In an early draft, we had Pablo looking at a map and seeing it as incomprehensible squiggles. I feel like that's what it must look like at first. On the other hand, there's little New Yorkers love more than helping people who are lost on the subway. We cherish our bubbles of anonymity, but we're also eager to seize the rare moments of connection (and perhaps also the moments when we get to show off our own knowledge). It's hard to get lost in New York, the natives love to tell you how to get where you're going.

So they may not give you the time of day, but everyone will tell you the best way to get from point a to point b on the subway?

Exactly!

You mentioned that you originally thought of it as taking place on a map, but after abandoning that idea you kept one page like that and that similar approach to space is there throughout, like in the elevators at the Empire State Building. Where was the overlap between your initial idea and Sergio's approach?

I knew from the get-go that I was working with him and it's an element that I had really admired in his other work. I was trying to build in places where that would be able to shine.

One of the things that's beautiful about comics is their ability to plunge you into a world that can be nearly architectural in its precision, and yet imaginative and abstract at the same time. My dad says comics are the art of turning time into space. I love the way Sergio conceptualizes space, even when it's not a map, into something that looks like a map. This book didn't come from a formal place, but I'm sure there are formal ways of talking about it.

There's that page when they arrive at the Empire State Building and they're in motion across the page but everyone else is frozen in time. It could be that the line isn't moving and so they are literally the only people moving, but it does give this sense of how the kids are experiencing the moment at a different pace than everyone else.

One of the things I appreciate about New York City is that, in the sea of people, you feel anonymous, and yet you also feel so individual and alive and yourself. When my mother first arrived in New York from Paris in 1974, she describes the sensation of walking down a crowded street, no one looking at her, and thinking, "I could die right now and no one would ever know." For her, at the time, it was an intensely liberating thought. I think there's something unique in the experience of moving through a city alone. You notice things when you're by yourself. You have different kinds of feelings about being in the world. I was trying to capture those emotions a little bit.

When they split up, Alicia notices pairs of friends all around her, and it brings her a strange comfort. When Pablo is by himself, he feels instead the intense loneliness you can have only when surrounded by other people. I think that's something that fades when you live in the city for a while. Eventually, it doesn't make you feel as lonely anymore. It makes you feel alive.

There is this idea of New York being cold and fast-paced. Would you say it's really about busy people moving at their own pace and somehow it just works, but like the subway it's very intimidating initially?

It's this mass of people swimming around each other, but you don't end up bumping into each other a lot. When you're on the subway, it's different than the street. There's something about being in an enclosed space with strangers. A whole new form of etiquette has to arise, like on an elevator. On the subway, you're allowed to look and hear and be aware of the other people around you. I love it for that reason. I play a game on the subway sometimes where I'm alone. I listen to the conversation of the people behind me and I try to imagine what they look like. When I've gotten a very good mental image, I turn around to check and I'm invariably wrong. I find that wonderful. It's a reminder that New York isn't just filled with stereotypes and archetypes, but all of these extraordinarily specific human beings.

Why did you decide to also offer a Spanish language edition of the book?

Sergio is Spanish and Pablo is meant to be a Latino character, so it made sense. It's also so that it could be read in schools more widely. As well as being a good tool for learning how to read, comics are a wonderful tool for learning another language for many of the same reasons. They provide visual cues to help you figure out the words and they make you want to know what the words say. Toon has done a number of forays into Spanish books and presenting their books in other languages on the website. It emphasizes the universal nature of comics.

I mentioned to someone that I was interviewing you and the person half-joked that of course you make comics, you probably spoke comics before you spoke English.

That phrase rings true to me. [Laughs] My dad sacrificed a very valuable comic collection to my desire to read in the bathtub. My brother and I weren't allowed to watch television, but we were absolutely uncensored in terms of what we wanted to read. We weren't necessarily reading comics for kids, although my mom did read to us from a lot of French comics. We were reading R. Crumb and EC horror comics and whatever we could get our hands on. [Laughs] "Maus" was the only book where they were like, you probably shouldn't read that one. It's not for kids. [Laughs]

Now that "Lost in NYC" is coming out, are you writing another comic?

I'm going to make another book with Sergio, which I'm really excited about. We're going to do it about Paris, most likely with the same characters, Pablo and Alicia. The characters are named after Sergio and Lola's kids. Lola Moral, Sergio's wife, frequently scripts and colors his work. In the subway book, Lola did the coloring (it's superb!) and she helped translate the book into Spanish. It's not just the Mouly-Spiegelman's who make comics a family business. [Laughs]

Anyway, Sergio and I are getting together in Paris in March and we're going to walk around and maybe get lost. [Laughs] I don't know if it'll be about the Parisian subway; we'll see what inspires us. That's a great way to be able to conceive of a book, and I feel very lucky.

"Lost in NYC" is scheduled for release from Toon Graphics on April 14.