Paul Tobin and Alberto J. Alburquerque's "Mystery Girl" #1 revolves around Trine Hampstead, a mystery girl in two ways: she can solve any mystery but the one about the origin of her own powers. Tobin leaves the mechanisms of Trine's powers unclear. Her omniscience seems to be limited to people she sees in person. She hasn't set up shop on the internet. Despite the seeming necessity of face-to-face contact, she's more than a mind-reader. She knows things about a person's life they can't know themselves, or that nobody else knows, like when she informs a widow of the GPS coordinates of her husband's body in Vietnam.

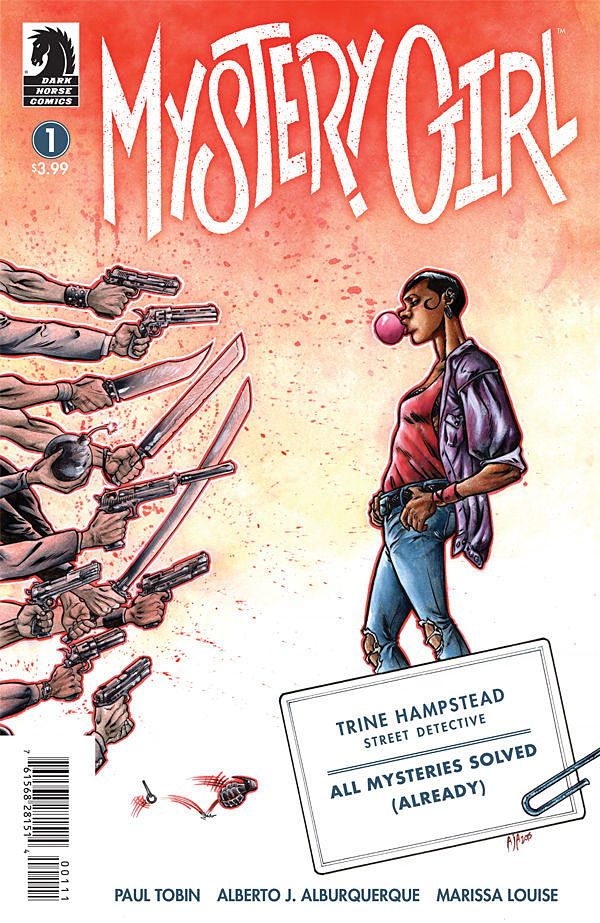

The warm, chatty opening scene isn't necessarily what the reader might expect, considering what Trine can do. With her powers, she could be a billionaire, a superhero or a supervillain. Instead, she's content with a simple life and has a place in a community that wants her, even if they aren't at ease with her spooky power. Her role is akin to that of a village healer or fortune teller. In an urban setting, the only way Trine's relatively quiet life makes any sense is if only a limited number of people believe in her powers, and everyone else (even her boyfriend) dismisses her as a small-time scammer. Otherwise, governments and world powers would be far more interested.

Trine's meeting with Alfie is Tobin's too-obvious way to package an information dump about Trine's past. The characters of Ginger and Alfie get superficial treatment from the creative team. Alfie is over-the-top campy. Tobin's uptalk and airheaded rhythms for Ginger's dialogue are annoying and stereotypical, and so are Alburquerque's choices for Ginger's clothes and the unnecessary nudity. However, Trine's answer for Ginger's small mystery is both surprising and believable. It's an excellent example of Tobin's gifts of writing serendipitous moments, reminiscent of his work on "Bandette." His dialogue gets much better in Trine's farewell scene with her boyfriend Ken. Tobin writes their conversation with a poignant combination of banter and melancholy, assisted by Alburquerque's excellent body language for this scene.

Alburquerque has a knack for pretty background details, like the curvature of a birdcage and textures for a shopping cart and a straw basket, but his panel compositions often feel cluttered. He creates a wide range of faces and bodies, but there are excessive wrinkles in the clothing aren't true to the way clothes drape in real life. His facial expressions are often too exaggerated and slightly stiff, even when the body language is more subtle. His linework lacks the illusion of depth.

Marissa Louise's colors technically pay attention to the direction of light with some nods to shading, but her approach is too uniform to give any scenes the appearance of illumination by natural or artificial light. Everything looks bland and grayish. In the hotel scene, the near-monotone of purplish hues flattens Alburquerque's linework, and the same goes for the flashback that is colored in blues. The transitions are clear, but only at a cost to the other aspects of the art.

The trajectory of "Mystery Girl" #1 is classic. A new mystery sparks a desire in Trine to leave her cozy sidewalk business and see more of the world, which will cause her path to converge cross with the killer who is introduced in the second scene. The eventual convergence is so predictable, the ending cliffhanger feels weak.

The surprises are in the details, like the killer's puzzling conversation with a maid. Tobin's script has one twist after another, each of them fanciful and offbeat, but the cost in believability might not be worth the charm and the unpredictability. By the last page, Tobin asks a lot of the reader. The killer's quirks and a zoological phenomenon out of left field require even more suspension of disbelief than Trine's powers. It's uncertain whether the eventual answers in future issues will be satisfying enough to justify these leaps. "Mystery Girl" #1 is uneven debut issue, but its strengths are unusual enough the reader may be hooked nevertheless.