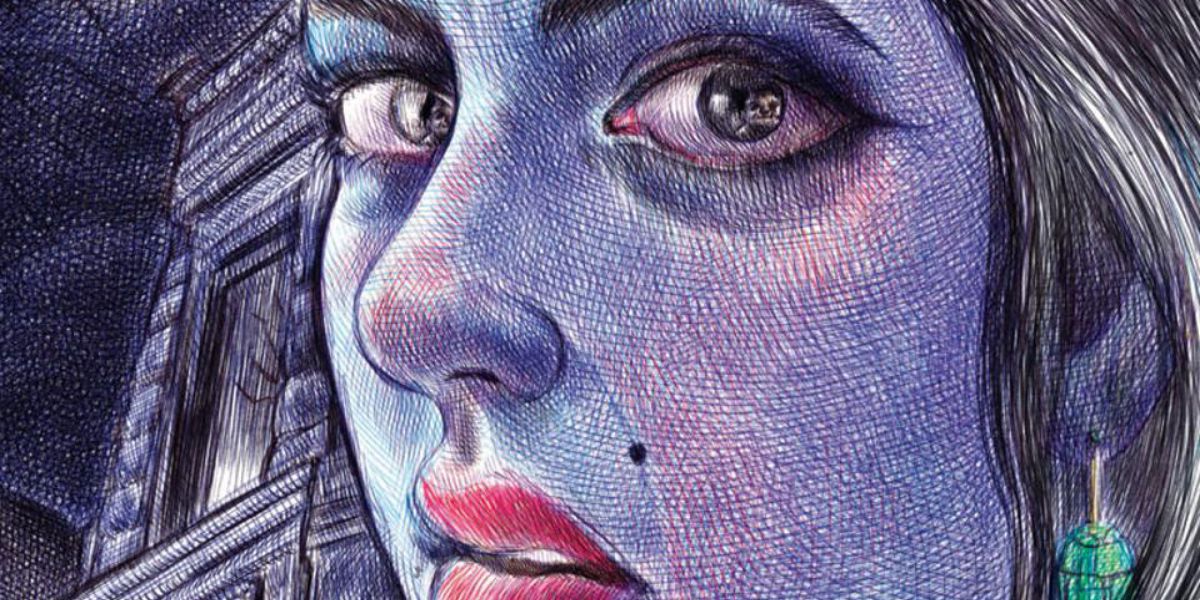

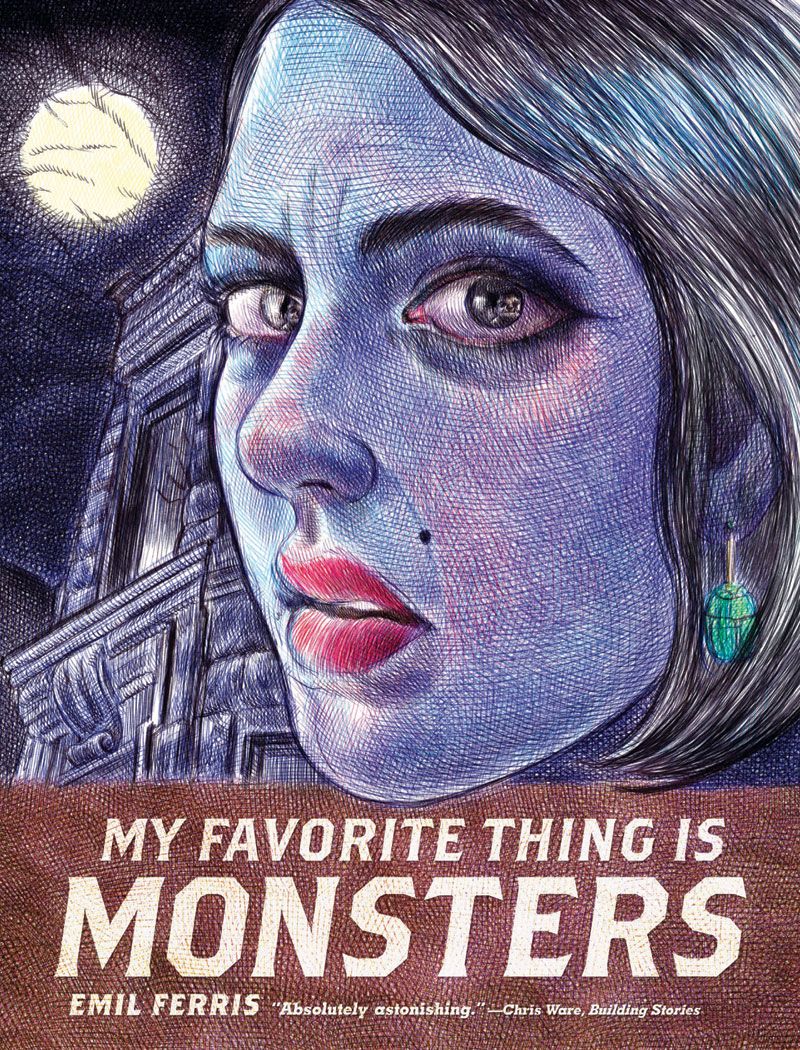

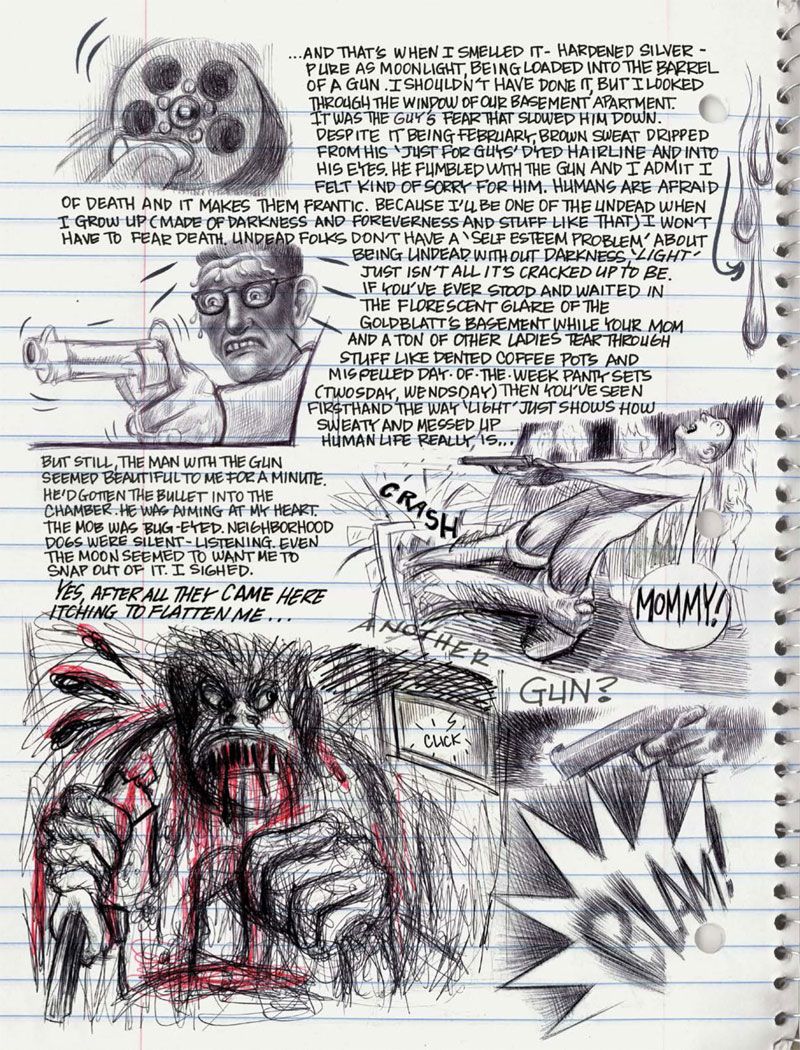

"My Favorite Thing is Monsters" is the story of Karen, a young mixed race girl growing up in 1960s Chicago. The conceit is that the book is Karen’s notebook, where she draws herself like the Wolfman, and is trying to figure out the racial tensions of her neighborhood, the death of her Holocaust survivor neighbor and the all-too common cruelties of the playground and the streets. It is a beautiful and striking book, a story that could only be a graphic novel, and in development as a feature film at Sony with director Sam Mendes.

2017 is still young, but this debut graphic novel from Emil Ferris is already being acclaimed as one of the best, most ambitious comics of the year, with praise from Art Spiegelman, Alison Bechdel and Chris Ware; not to mention NPR, The New York Times and other publications. It’s easy to see why. The book is alive and complex, managing the rare feat of capturing the perspective of a child old enough to start seeing the world in all its complexity, but still young enough that it doesn’t make sense. That gap can haunting, as the reader pieces together and sees what the protagonist cannot, and has rarely been used as effectively in comics.

Ferris sat down with CBR to talk about the book and her life. She grew up in Chicago and dealt with some issues, and while the book is not a memoir, it is an intensely personal book. Ferris spoke openly about many of the challenges that she faced in making this book and about the importance of these ideas and concerns, which, sadly, are topical than ever. The book offers possibilities about what comics can be, and a call to what we as people can become.

CBR: “My Favorite Thing is Monsters” a fabulous book and I feel like still trying to wrap my head around some of it. This is first book. How did you come to comics?

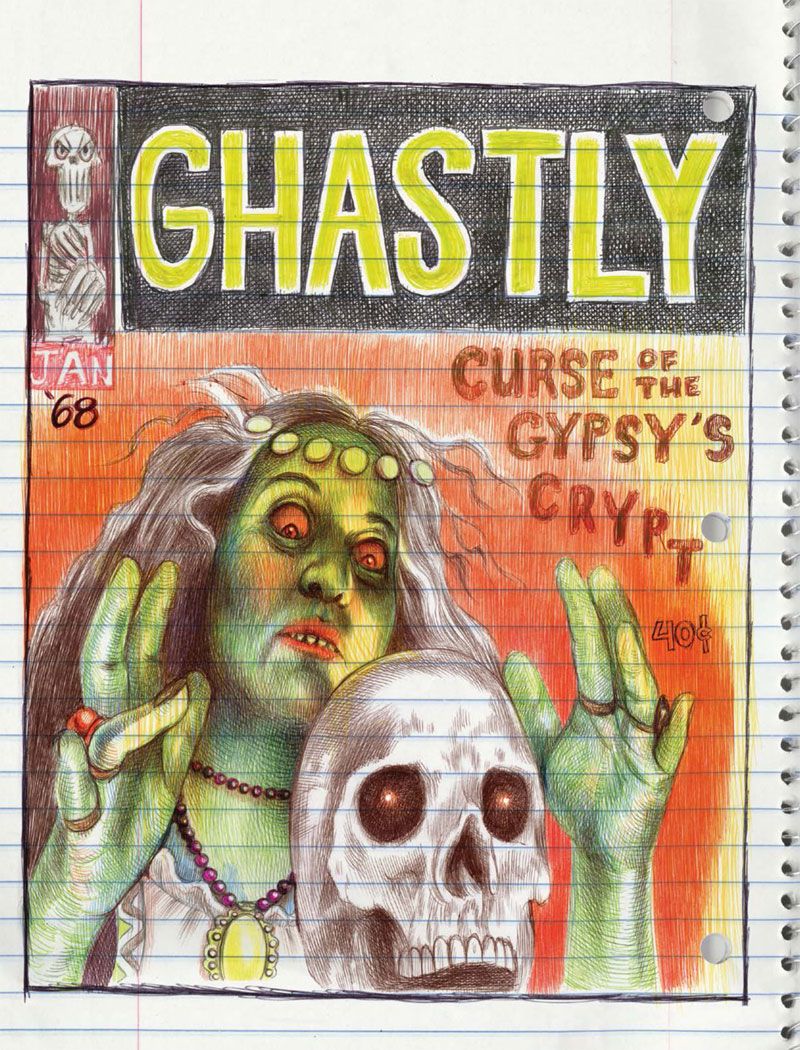

Emil Ferris: It’s something that I ask myself, because in some ways I don’t understand what happened to me. [Laughs] There was this long period of time where I was alone with this thing. I was on my own with this monster, that I was grappling to put on my lap, and I asked myself many times, what are you doing? How did this happen? I started out with an interest in horror and also characters. My father was an artist and there were a lot of comics available to me. He had an enormous collection and I was not foresworn from reading horror comics -- thankfully. I loved horror. Not the terribly frightening recent movies, I loved the B-movies. As a very small child I would stay up on Saturday night and drink as much Coca-Cola as I could so I could make it through it through the two features. I started doing this when I was five. Also, because my parents were very liberal, I saw things like "The Virgin Spring," which was astonishing and brutal. Of course, I grew up in the 1960s in Chicago and there was an awful lot of real-life horror that was part of my life.

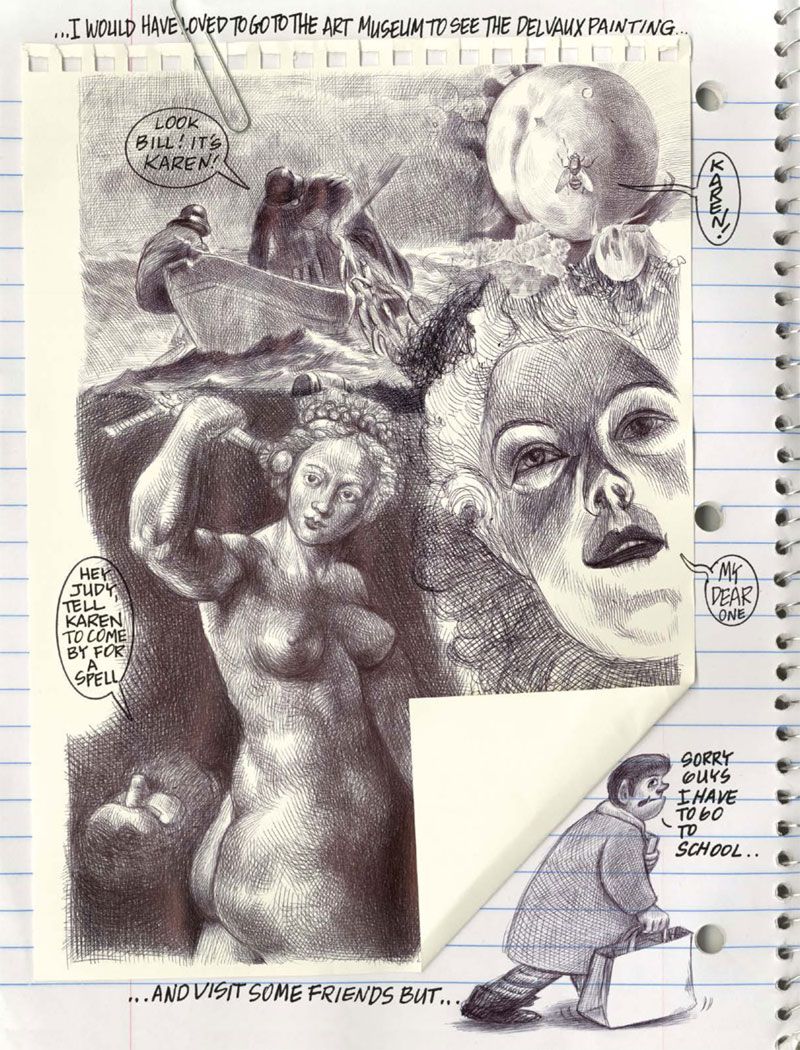

Throughout my life, I was trying to be a fine artist and I just would start weeping with frustration because if you do an image that doesn’t have words, then you’re not able to continue the story. The image has to stand alone. When I was eight years old, my grandmother started sending me one Dickens edition which contained these fantastic engraved illustrations and as soon as I finished it, she would send me another one. That’s when I realized that you could write something that would have many more words than you’d find in a comic. I loved comics, but I was always frustrated by the stories. I always wanted more text. I always felt like I had to really study those drawings and I felt like there could be more equity between text and image and they could work differently together. I wanted to slow it down.

You clearly want the reader to spend time with the art, and it’s very text heavy, and those two aspects are not always combined in the same comic.

Exactly so. We’ve become such a visual society and it is very difficult to communicate anything without visuals attached. People are just not really interested in text only pages. It draws them in now in a way that in the 19th Century it didn’t do to the same degree. I’m very happy to be at this point and I’m lucky enough to have this ability to draw so that I can add that to the story. Or vice versa. I don’t know how you’d put it because it is such an organic process. It doesn’t just rest on text or drawing. I don’t write the whole story out. I do as much drawing to figure out what will happen as I’m writing it.

Was this idea of framing Karen’s childhood in terms of a mystery and a monster story there from the beginning?

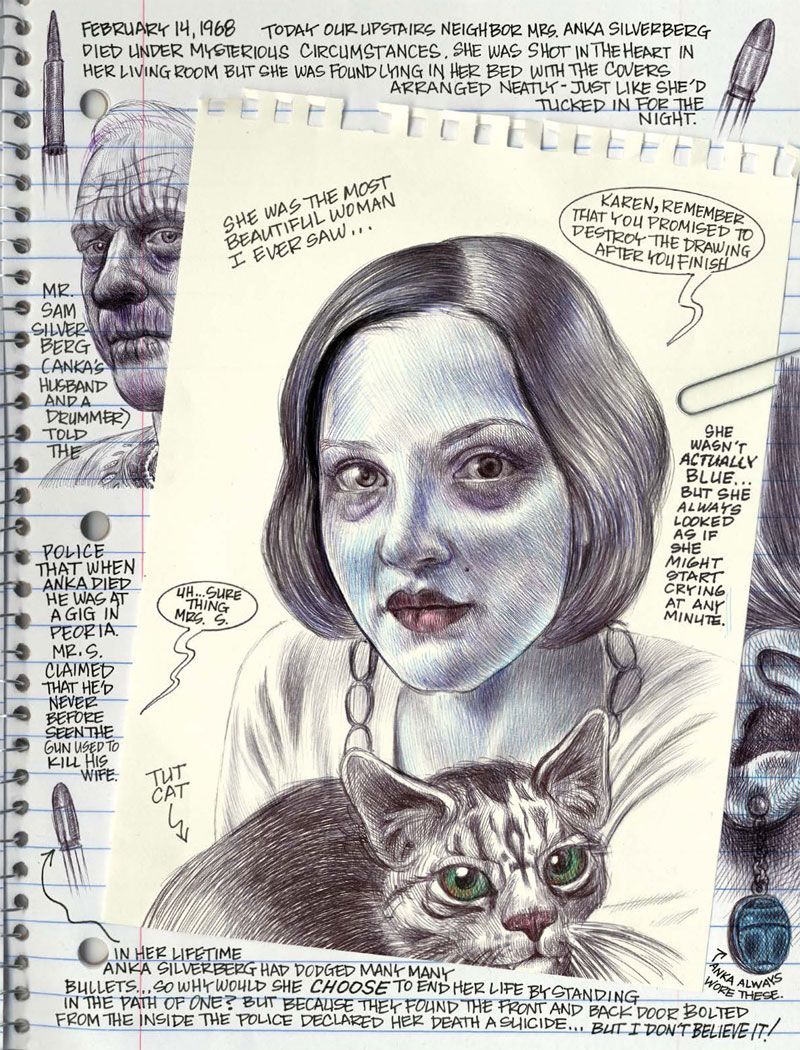

I felt like mysteries and monster stories have a certain cohesion. There always is a mystery inherent in a monster story and there is a certain monstrousness in a mystery. I grew up in Chicago and by the time I was 10-11, we moved into a neighborhood in which lived many survivors of the Holocaust. My mother was an artist. The owner of the gallery where she showed her work was a Holocaust survivor who had the numbers tattooed on her arm. I knew her pretty well and I knew my neighbors. I visited old folks homes and I heard stories. These people were dying and their lives were pretty mysterious, they had survived really horrible things. I felt there was some kind of connection between what they had gone through and monster stories.

I had always loved the wolf man. I love the old movie and I found out that Curt Siodmak, who was the writer of the movie had fled Europe. He said that the appearance of the pentagram was something that he had assimilated from having to wear the star. It was this sense that doom is coming. The star was this symbol of the coming mark that was on you and you were going to be destroyed. I always sensed that there was some connection between that story and what my neighbors were telling me.

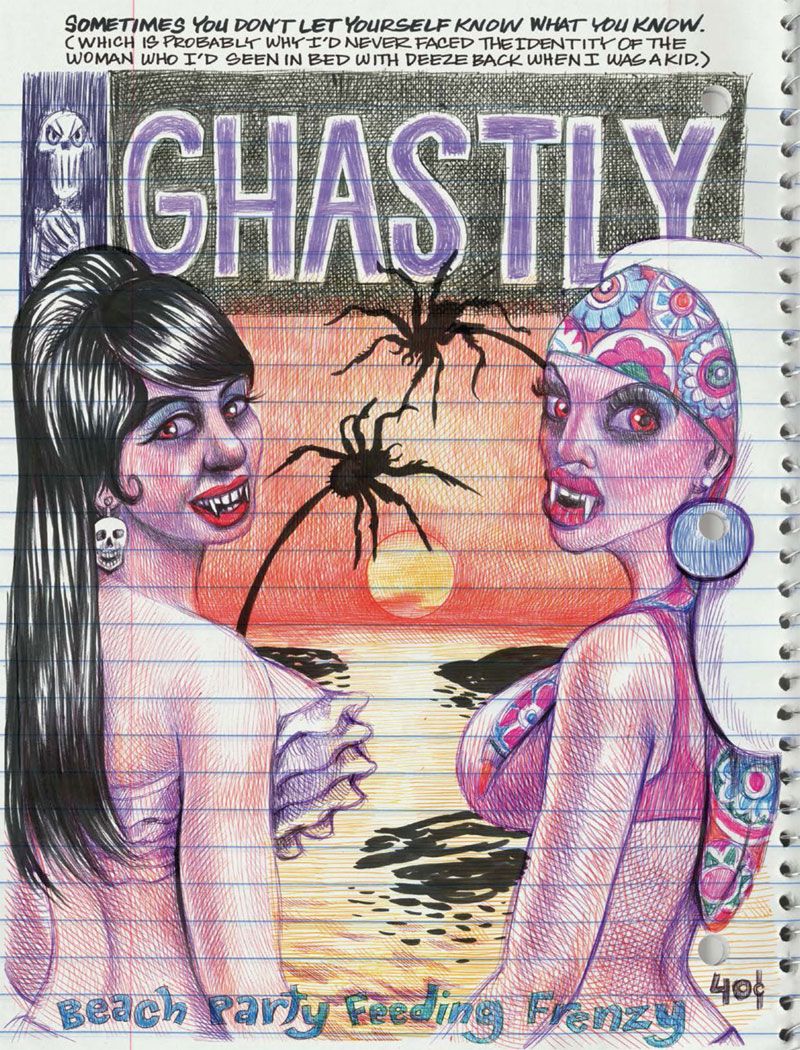

That is interesting. I know that a lot has been written about werewolves and feminism, the monstrous self and the moon cycle.

I didn’t realize that! This is covered in the second book, the idea that the love of werewolves and the love of the idea of the transformation -- the capacity to not be human -- is really a refutation of what it is to be female. Where you’re heading towards puberty and you don’t want to be whatever you see. Now I look at young girls who are in a country being led by the kind of person who said the kinds of things he said, and I think that they are more marginalized and more objectified than I think that they’ve been in recent history. It is a fearful thing to imagine being a woman in a society that would talk about you in that way. My character doesn’t relish the idea, and would much prefer to live in a lair and be forced to occasionally feast on human flesh. [Laughs] As opposed to becoming the victim of cancer and the victim of social inequities and just un-empowered. Being this big vicious creature would be so much better than being that.

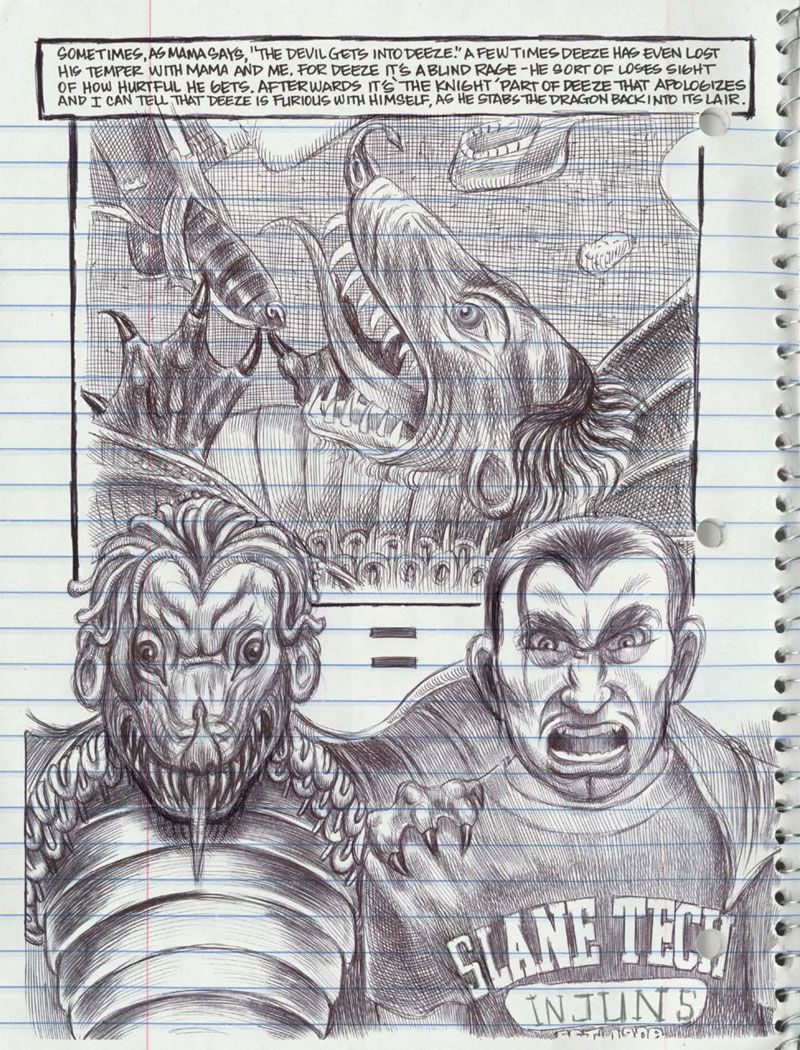

Towards the end of book, you make an observation about the difference between a good monster and bad monster. “A good monster sometimes gives somebody a fright because they’re weird looking and fangy...a fact that is beyond their control...but bad monsters are all about control...they want the whole world to be scared so that bad monsters can call the shots.”

Right. That’s something that I think we really have to know and understand. I think maybe we are getting a lesson in that.

The conceit of the book is that this is Karen’s notebook and did you have that idea from the beginning?

That was a very important part of what I did as a child. I was disabled as a child very seriously. I had scoliosis and most of the days of my life were spent unable to do the things other children did. So I drew. That’s how I dealt with not being able to run or not being able to play like most kids did. Then I realized that the kids were very interested in my sketchbooks and my notebooks. They wanted to spend time looking over them pouring over them. Those were probably the first graphic novels I ever wrote. I realized that when I would write an essay or do a history assignment in school I would illustrate it and sometimes I wouldn’t get them back. [Laughs] Sometimes I would get them back, and other kids would ask, "Can I keep this?"

I was very lonely at recess because I couldn’t run. I was a little monster. I realized that if I started telling ghost and horror stories I would get a small cadre of kids. I think that’s where storytelling began for me. It was a way to make connection. It was a way to have friends. Also most of the kids I went to school with were black and I’m a person of color but Chicago is a pretty racially divided city in some ways. The vestiges of structural racism were very evident in our school system. Most of the teachers were white and most of the kids were black and the teachers were in their fifties and were staunch Daley supporters and they had a certain diminishing attitude towards kids. Not only an implicit attitude -- frequently it was quite explicit – and so the horror stories that I frequently told were metaphors. I didn’t realize it until later. You’re responding to the cry of the universe when you do that and I honestly did not know consciously that that’s what I was doing. That’s what happened before the book happened.

These questions of race and poverty are present throughout and Karen is at the age where she’s becoming aware of it but she doesn’t really understand what it means. She just knows that this is how people act and at that age it’s something that you have to treat as matter of fact, because you don’t understand why.

It’s an enormous sorrow when you’re a child. What you see and what I saw was lost promise. Some kids succeeded wildly and created great lives for themselves -- despite the odds -- but although most of the children with whom I was friends had remarkable gifts and intelligence and great promise, for a great many of them the trajectory out of childhood was not a positive one. It caused me a great deal of sorrow. I saw it for myself in terms of how I was treated too, but it was much more so if you were black. I saw real cruelty to kids who identified as gay. I really wish this book were a history piece but unfortunately it feels current. When I started writing it, I can honestly say that it didn’t.

Karen is listening to tapes of her neighbor talk about 1930’s Germany and Anka talks about being forced to wear the star and some people would ignore her, but other people went out of their way to be polite to her -- because it was the only thing they could do. That’s a scene that’s much more chilling today for many of us than I think you ever meant.

Exactly. I have Jewish friends who say, when they do this Muslim registry, we’re all signing up. I think, my god, here we are. How did this happen?

How long have you been working on this book?

I began a 24-page comic that was my thesis when I was getting my graduate degree. I began that then, but prior to that, to challenge my shyness, I decided that the only way was to go all badass on my shyness and take theater classes. I took three years of theater classes. I felt like through theater you learn an awful lot of truth about yourself and about other people. I began writing this story about a werewolf girl who is in love with a Frankenstein gay man. She’s a lesbian and they love each other and he’s trans and they love each other. I began writing about it then and this was more than 20 years ago. I never really stopped thinking about her and this other character and this unusual relationship. It came out in Karen in this book.

When did you turn to making the graphic novel?

I was getting in trouble because every time I wrote a poem, I illustrated it. I guess that was a sign. I loved that confluence between the image and the word my whole life and it seemed like a natural thing. There were formal objections. There were a few teachers who were traditionalists and they didn’t really understand the medium, but I almost couldn’t do anything else. I had this in me. I wanted to explore how a story could be fueled from text and image and I felt like I needed the whole arsenal of my abilities to relay the story.

You attended the Art Institute of Chicago, is that right?

I got West Nile Virus and I was paralyzed from the waist down for about nine months. After that I was in a wheelchair and I started in the wheelchair and lots of art and physical therapy. I lost the use of my right hand, but luckily a lot of my ability came back. Not all of it. I still have some issues with my right hand but I worked through them. I started in a wheelchair and I ended walking so my final graduation walk was a big victory for me.

Throughout the book there are copies of actual paintings and the way that Karen describes visiting the art institute, there was something very lived in about that.

Thank you. That is absolutely the case. My father was a football player and a wrestler and a boxer, he was a very virile guy, and he loved to draw. He made eight pagers and used the mimeograph machine at school he ended up being caught by the art teacher. She said, we can expel this kid, but he’s got real talent so let’s not do that. [Laughs] It was a lot of Minnie and Mickey getting up to no good. She was his mentor and got him into the Art Institute on scholarship, which is where my parents met. They were both students there. We weren’t religious people. Art was their religion and the Art Institute was church. I had that feeling my whole childhood. These paintings were symbolic of deep things you could learn if you spent time with them. I was pushed towards paintings the way some kids are pushed to memorize Bible verses or parts of the Quran.

Did you use a lot of models for the figures?

Some. Some I just made up out of whole cloth. One of the things my father taught me was he would get on the L here in Chicago and he would stealth draw people. He was drawing people in restaurants and just everywhere we went. Drawing all the time was a family value. I learned to do this and I think I’ve just drawn so many faces of Chicago that I could spill them out when it was required.

You have a second book out at the end of this year. Do you want to say anything about it?

The second book is to a great degree about Karen grappling with her sexuality and the realization that she is attracted to women and at a time when there’s no representation for that whatsoever. In "Dracula’s Daughter" and these movies there is homoeroticism. The Dracula story is a very homoerotic story, but it’s not explicit. Karen is dealing with what it is to grow up and be lesbian and not feel that there’s anywhere she can look to see what that looks like.

Have you finished the second book?

Pretty much. I was really tender around certain topics because I felt like I didn’t need to be explicit in a certain way, but then I realized the climate in the country was changing and shifting. There was an affront to the rights of people who are not heterosexual and I decided, well, I’m going to have go full-on to make the points that I need to make. I want people to have empathy. I want them to live inside the life of somebody who doesn’t represent them and I want them to feel those feelings and experience that life. To understand that they are responsible for creating a world where every single person can live to their fullest. To understand that to constrain people by virtue of bigotry is a loss for everyone.

Having finished this huge project, what does it mean to have it finished and out in the world?

It’s kind of astonishing because I spent a lot of time in total seclusion with this. To bring it out and have people respond to it -- of course it’s what you want -- but it’s such a different experience than making it. Talking about it is so different and I’m trying to wrap my head around that. As a naturally reclusive person it’s a little daunting, but I don’t mind doing it. A friend of mine, Bridget Montgomery, said, Emil, you have to change your focus. You have to you made this book out of generosity – being generous with the images, being generous with the text, really caring about the reader experience was such a big part of what I did. I wanted to give my readers the most articulated experience in the drawings I possibly could. I labored over them because I wanted there to be a lot there for them. She said in that spirit you created the book you need to talk about the book and give people in a dialogue about the book. How can I be true to the things that I believed in while I was writing the book. Now that we’re seeing this political shift and a change in the climate of the country I think it’s more important for me to be doing that and to stay in that spirit of generosity and openness.

This is your first book and I’m holding a copy and on the front cover is a quotation from Chris Ware calling you “absolutely astonishing” and on the back cover Alison Bechdel calls this a “spectacular eye-popping magnum opus.”

I don’t even know how to take that in. I sometimes just put myself aside and say, they’re talking about “her.” Then I can deal with it. I mean these are my heroes. Alison set me free. Chris Ware set me free. Art Spiegelman set me free when I read “Maus.” I knew I had to talk about these things because of these people. So to have them reflect positively on the book is an extraordinary, unanticipated joy and privilege and honor. I’m hopeful that if people can see through Karen’s eyes, it will expand on some of their thoughts about who they are and who other people are. I think some people are emboldened to go out into the world with their beliefs and do amazing things. I just think that maybe folks who want to constrain the world have to challenge that in themselves and heal and become bigger.

This is a call for everyone to realize their mission in the world in a positive way. If there could be something that you wanted to accomplish that you’ve been thwarted from doing, that you’ve been diverted from. Maybe people wouldn’t be so much interested in being bad monsters if they would decide to be good monsters -- really just understand their nature and live within their giftedness and produce things that give them joy and believe in that.

It took me six years to do this. I was a single parent, disabled, struggled with a pretty severe disability, didn’t have a lot of financial resources. If I can do this, I think a lot of people can. Maybe it won’t take the form of a graphic novel, but this is the kind of work we should be doing. We should be encouraging people to live in their giftedness and their wealth. I hope that’s what happens. Sometimes I get on the L to stealth draw and when different people sit down -- and they come from all different kinds of backgrounds -- I can tell their engaged with the drawing and sometimes they talk to me and they express a joy for drawing that they lost when they were children. I carry extra sketchbooks with me and I give them a sketchbook and they are just flummoxed. [Laugh] I say this is important, what you were doing was good, and you need to keep doing it and believing in it. I really think that’s the way we need to go. I think we need to let down all of this and just start loving what we loved when we were children. We loved what we really are, and I think a lot of people have forgotten themselves.

"My Favorite Thing is Monsters" is available now.