Dean Motter is an award-winning designer and editor who has worked in an out of comics for years, but while he’s not the most prolific comic book creator, he is responsible for some of the most important and influential comics of recent decades. He’s the writer behind the 1980s comic series Mister X, collaborated with Ken Steacy on the cult classic graphic novel The Sacred and The Profane and then wrote and drew The Prisoner: Shattered Visage, an authorized sequel to the legendary television series The Prisoner.

In the 1990s, Motter wrote Terminal City, two miniseries drawn by Michael Lark, which offered a very different approach to city life, in terms of tone, story structure and aesthetics, than his earlier projects. Motter also wrote and drew the miniseries Electropolis, and collaborated with Lark on Batman: Nine Lives.

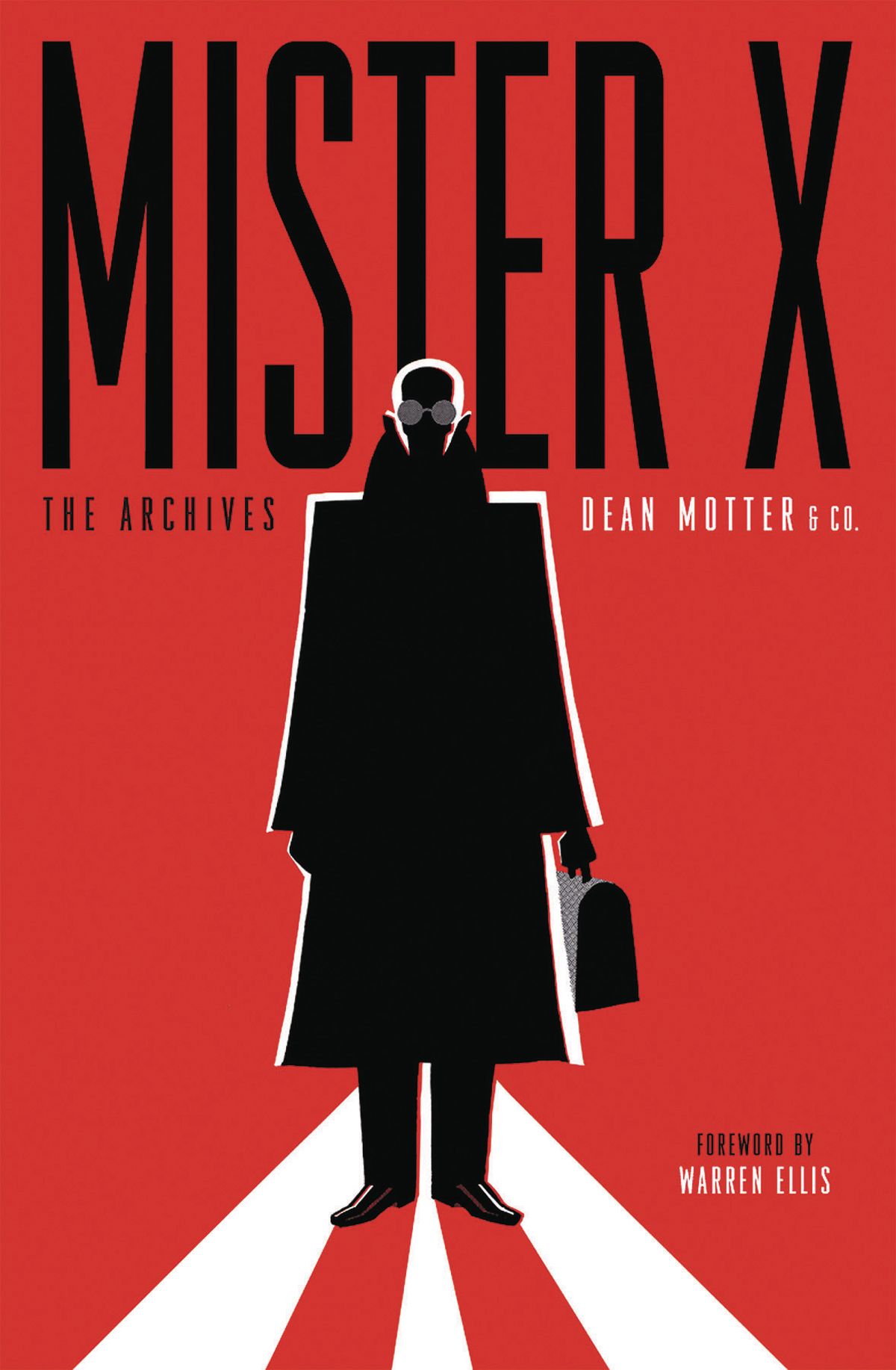

In the past decade, Motter relaunched Mister X, this time writing and drawing the series, which is published by Dark Horse Comics. Motter is also working on a wide range of other projects, including collaborations with the David S Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies. Last month, Dark Horse released a paperback of Mister X: The Archives, which collects the original 1980s run of the series; which follows last year’s Library edition hardcover collection of the two Terminal City series.

Motter sat down with CBR to talk a little about what he’s working on, and how cities have shaped his thinking.

CBR: This idea that how a city is organized and planned affects the people who live there is something that I think is a lot more commonplace today, but I first encountered this idea reading your comics. Where did that come from for you? Were you always interested in cities?

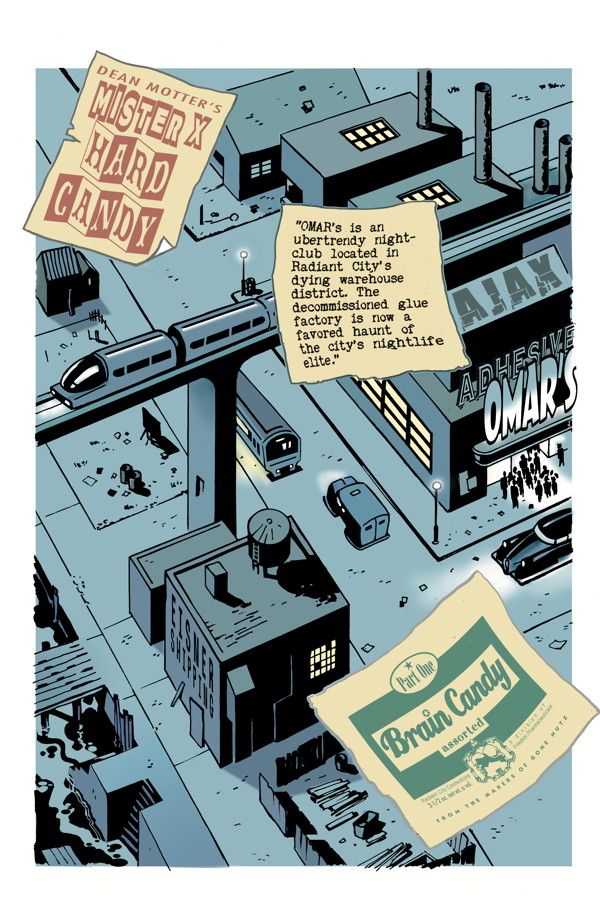

Dean Motter: I think this idea of a city as being more than simply a location, stage or residence for characters occurred to me when I first saw Fritz Lang's Metropolis in college. Coincidently it was screened in two different electives I was taking at the time. Theoretical Architecture and Film History. Not only was it a noir/science fiction/futuristic city, but it seemed to be populated by a citizenry which only that specific place could have produced. My epiphany had to do with how a city's anthropology and culture shaped its design, architecture and civil engineering. And vice versa. It wasn't a big leap to see the city as more than a storytelling setting.

Where did Terminal City come from? You're fascinated by cities, but this was a very different kind of project from Mr X, and a very different kind of city.

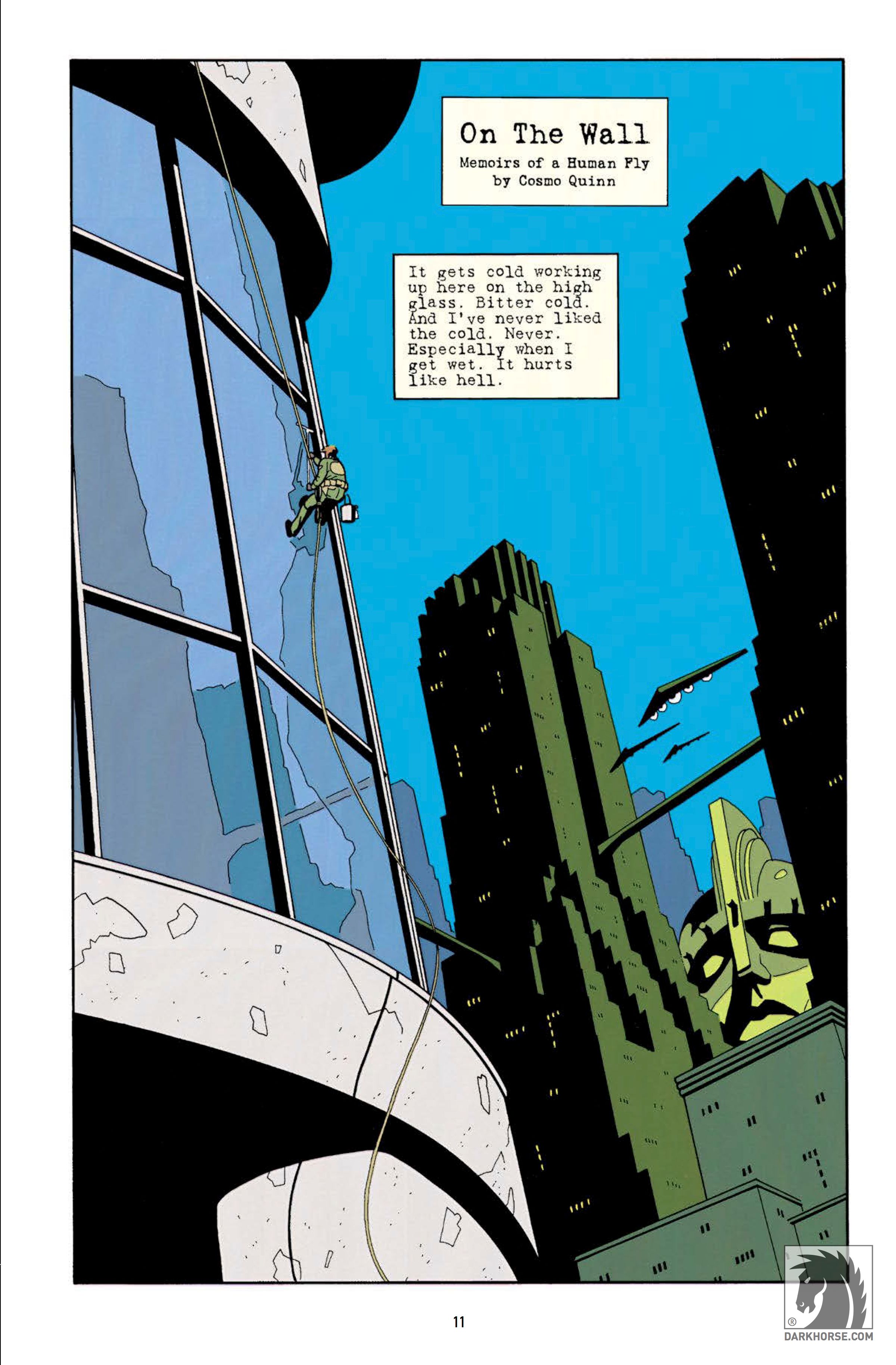

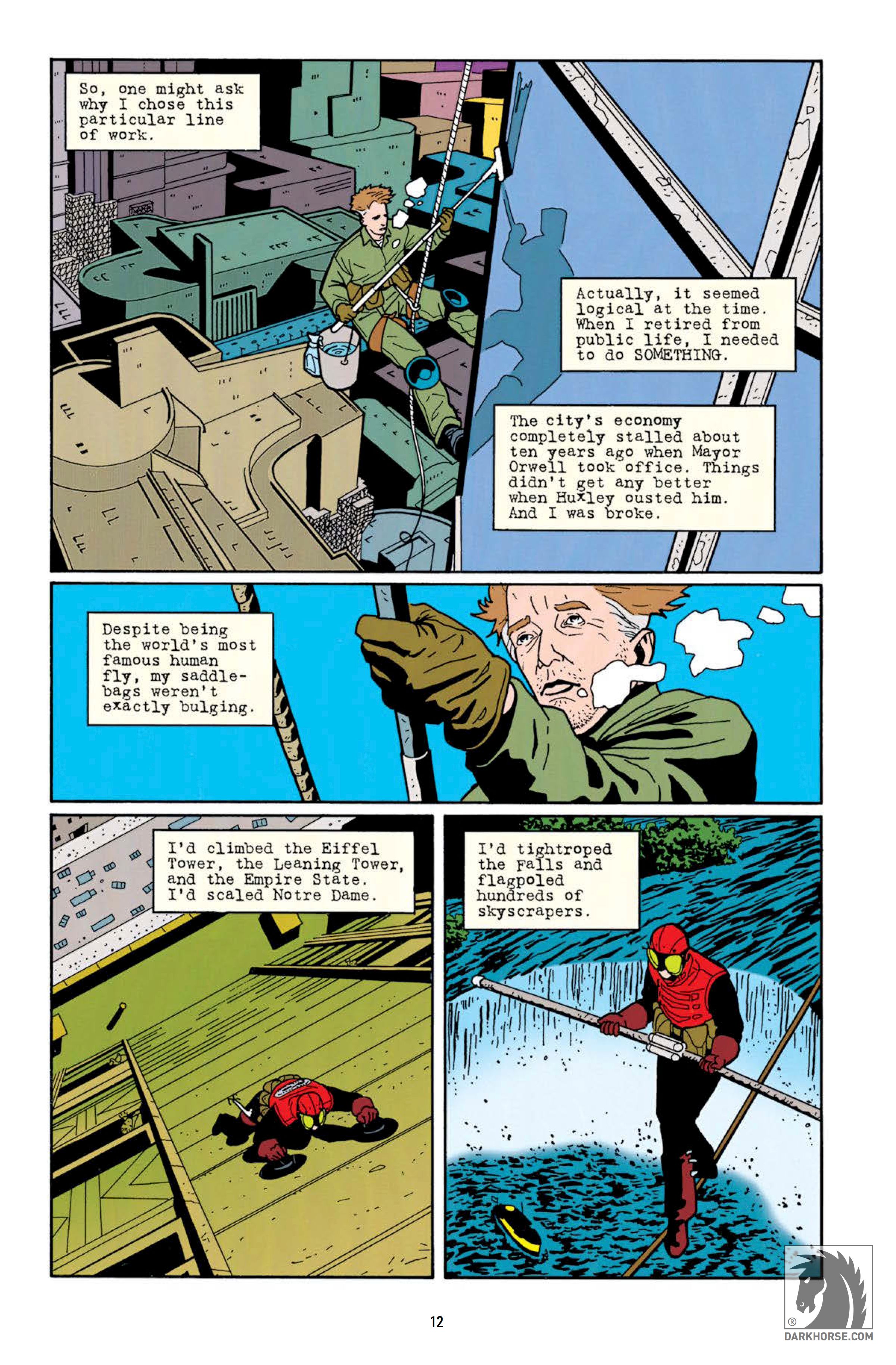

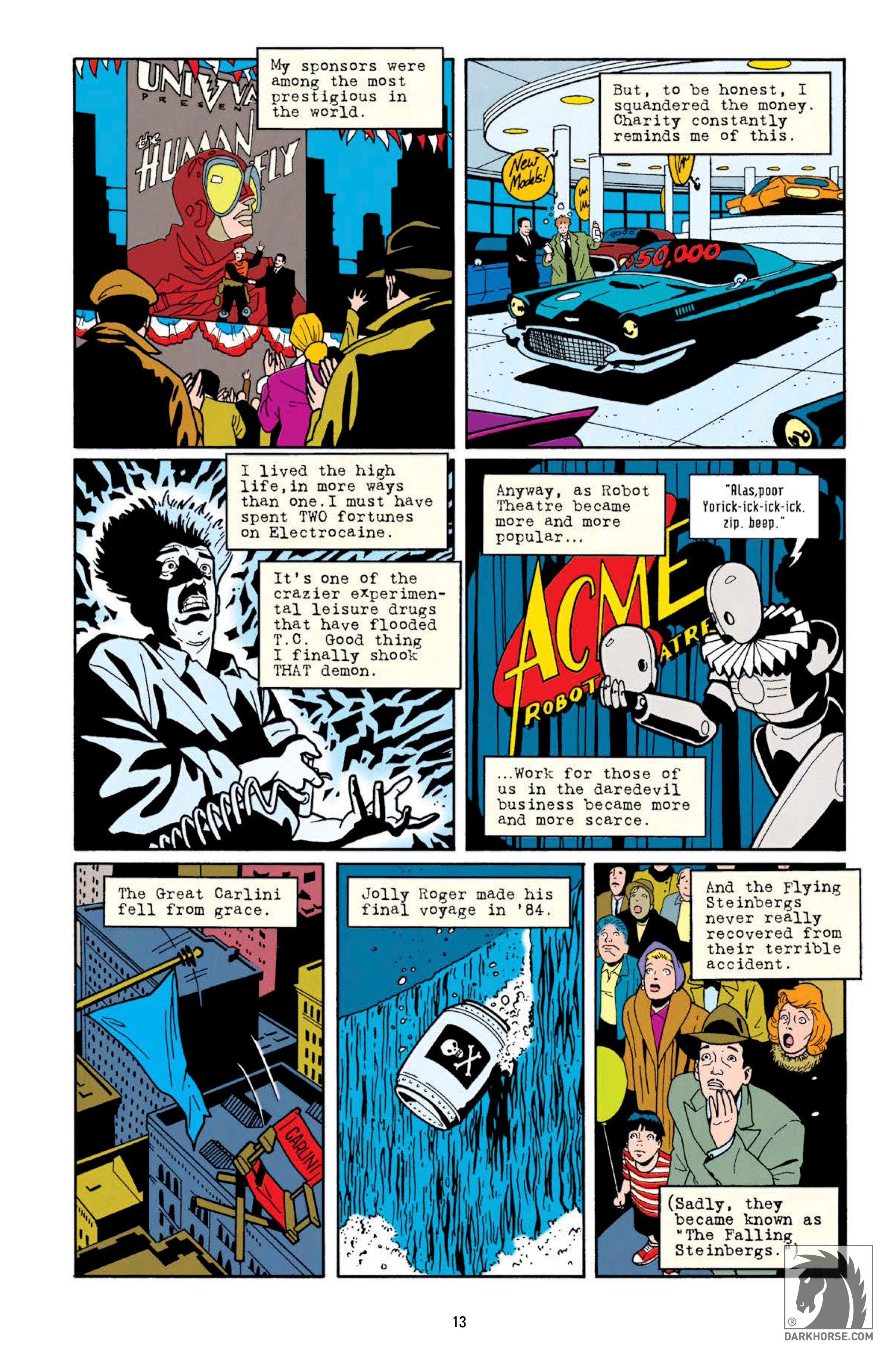

The notion of a retired human fly-turned-window washer came to me when I first moved to Manhattan. While I had lived in a big city for many years, most of it was at street level; nightclubs, antiquarian bookstores, galleries and diners, etc. In New York City I found myself in skyscrapers quite a lot (not that Toronto has a lack of such – I lived and worked – literally, in the shadow of the CN Tower – the world's tallest free-standing structure – but I had few clients with offices in the upper floors of the glass monoliths downtown).

While watching the New York window washers one day it occurred to me that they were daredevils of a kind. Similar to the Wallendas or Petit. In many ways living in, and being inspired by New York offered me the chance to actually explore the sort of world that had--up to that point--been more or less imaginary or theoretical to me. NYC had a history I had romanced all my life. Toronto's history only became important to me once I was a resident. When Shelly Bond-then-Roeberg approached me about doing Mister X for Vertigo the rights were still tied up with the original publisher. I offered to create something new. In the course of doing Mister X I had become obsessed with retro-futurism. The 1920–50s vision of the 21st century. So I crafted a new premise mixing all of these elements.

Terminal City was structurally a really interesting book, because it's a number of stories interacting and overlapping, centering around this hotel. Was that always the idea, to have this Robert Altman-esque story with a massive cast of characters, or did it begin smaller with Cosmo or another character?

It was always conceived of as a multiple storyline book. Mostly it was inspired by Will Eisner's The Spirit. The Bogart film Dead End. And, yes, Altman -- especially films like 1975's Nashville. And also from the crime TV shows from my youth like Naked City and Perry Mason.

What was it like collaborating with Michael Lark and what did he bring to the book or the characters that you hadn't anticipated?

Michael was a find! I had worked with him before, when Byron Preiss enlisted me to edit and art direct the Raymond Chandler Philip Marlowe graphic novels. He adapted The Little Sister. After that we knew we wanted to work together. By the time I began working at DC his work was already being auditioned around the office. We came back together almost by serendipity. I knew we had similar tastes in vintage design, film genres, etc. Working with him was a dream. He would complete my 'conceptual sentences' so to speak. And he made it look so damn easy. Shelly was an especially gifted editor and facilitator. When I asked for Michael, colorist Rick Taylor (based on his work on Batman Adventures) and Chiarello for the covers, she made it happen without blinking. After Aerial Graffiti, Michael and I had one more curtain call to take. In 2002 we got to do our dream: the Batman: Nine Lives graphic novel, a film noir Elseworlds take on Gotham.

Did you have more plans or ideas for Terminal City in mind?

Oh yes. My one big idea is a crossover serial that combines Mister X, Terminal City, and Electropolis. A Tri-City Murder Mystery. An exploration of the Lady in Red. I got a load of them up my sleeve. I hope I get to tell them all before my expiration date.

One reason I asked that is because Aerial Graffiti seemed to end abruptly. The last few pages flashing ahead and telling a few stories. Were you thinking that this might be the last issue?

I was hoping -- and there was every indication that the series would continue. But for some reason the second series wasn't as successful as the first, and DC chose not renew it. Electropolis was actually going to be the third series, with the Trans-Atlantic Tunnel race running as a parallel/background storyline

You mentioned that you had moved from Toronto to New York before you started working on Terminal City and I'm curious about how you experienced New York after that move.

As a kid in Ohio, I had always dreamed of New York. The place where Clark Kent and Spider-Man had their adventures. Where King Kong terrorized the populace. Where Car 54, Lucy and The Honeymooners played out. The place I'd always “lived in” via the movies. comics and TV. When I moved there I lived in a loft space in lower Manhattan, It was glorious. Not far from the World Trade Center (Ground Zero), it was both bohemian and cosmopolitan at once. Laurie Anderson, Philip Glass and Spalding Gray were neighbors. DeNiro, John Kennedy Jr. and Bette Midler had apartments in the neighborhood. So much of the previous century's features were still in evidence, be it the cast iron/mock-brownstone facades, brickwork/cobblestone streets, or industry/residence warehouse/loft symbiotic/retrofitted environments. If there was a way, I'd move back there in a minute. Mind you it's not the same place it was in the '90s (especially since 9/11) – but of course evolution is the city's nature -- and I'm not the same guy either. Still, when I see the city playing a role as something more than a backdrop -- in Woody Allen films, for instance or even 30 Rock reruns, I get very “homesick.”

How much of Toronto do you think is in Radiant City and how much of New York is in Terminal City?

Well, you hit the nail on the head. I often remark that Mister X was a native-born Canadian even though his creator is not. But yes. That became obvious to me early on. Toronto became “futuristic” around Canada's Expo 67 and never looked back. New York has always been in a constant state of renovation and adaptation -- the vintage and the state-of-the art have always been irritable neighbors. My comics have certainly been influenced by that dynamic.

For the past few years you've been returning to the world of Mister X. I wondered if you could just talk a little about what you've been doing and why you decided to revisit the series.

Diana Schutz approached me with the idea for her NOIR book. The rights situation with the original publisher had been cleared up and it was no secret that I had always wanted to draw Mister X myself, but my career never afforded me the time. Collaboration was the only way to tell my stories. Of course, it helped that I truly enjoy the collaborative process, but still. After writing The Prisoner, Terminal City, The Heart of the Beast, Superman Adventures, Batman: Nine Lives and even the two Star Wars Tales I did for Dark Horse, I felt I was a much better writer and that technology finally allowed me to do Mister X solo.

Rather than picking up where I left off, I thought it better to reintroduce the character to this new millennium -- to, in fact, a new generation of readers. After all, the property had essentially been dormant for a couple of decades. Plus, it gave me the chance to polish the premise with the benefit of 20 some years of hindsight and experience.

What has it been like writing and drawing the series as opposed to the first series in the '80s when you were collaborating with artists on the book?

It's more fulfilling in some ways. But it's also more challenging. The fiscal mechanics of producing the work aside (when I did The Prisoner, it was a major project for my entire studio staff, now it's all but a one-man show) I find that often I still write, as I did with Terminal City, with the underlying assumption that the illustrator would address many of the lacunae in the script with the advantage of a separate imagination and a fresh set of eyes. It's not unusual these days for me to curse the author under my breath, “what was he thinking?”

You've been working on Mister X for a couple years now and Dark Horse reprinted Terminal City recently in this very nice library edition, would you ever consider returning to tell more Terminal City stories?

Oh yes. I'd love to do that. Especially if it meant working with Michael once more. But I'd surely be open to another collaborator if he is engaged elsewhere, as he must surely be. I'm in awe of how Mike Mignola handles the Hellboy universe as a solo act as well as collaboratively. That's what I would like to aspire to.

So what's next? What are you working on now?

I have done some non-fiction comics for the David S. Wyman institute associated with the Holocaust museum – The Book Hitler Didn't Want You to Read, Karski's Mission and currently, Condemned by the President. I have also just completed a graphic novel adaptation of Eliyahu Goldratt's best-selling business novel, The Goal. Other irons are in the fire, including seeing Radiant City make it to the screen in some form, but the next Mister X mini-series Excavation is taking up most of my attention at the moment.