Welcome to the ninth installment of Page One Rewrite, where I examine comics-to-screen adaptations that just couldn’t make it. This week, we're looking back on Pulitzer Prize winner novelist Michael Chabon's pitch for a Fantastic Four film, all the way back in 1995.

When Michael Chabon wrote about his experience pitching Fantastic Four, he acknowledged he was not an obvious choice. At the time, Chabon's second novel had just been released, and he was in the process of developing a romantic comedy for Hollywood. Nothing in his resume indicated he was a match for a superhero adaptation, but Chabon requested a meeting to pitch his ideas. Chabon has been open with his advocacy for genre material, incorporating the world of comics into his 2000 novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, and later going on to co-write Spider-Man 2 and showrun the new Picard series.

Chabon's treatment opens with a significant declaration: "The first thing I want to say is that the Fantastic

Four are not about Darkness."

Chabon explains that the Fantastic Four were conceived in a different era, before the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the Vietnam War, Watergate, AIDS, crack, Bernie Goetz and all of those other things that didn't start the fire. Though technically created in the 1960s, the concept truly represents the innocence and optimistic spirit of 1950s genre fiction. The team's origin, which Chabon suggests just glossing over, doesn't hold up to any scientific scrutiny, and the characters' powers could easily be viewed as silly.

Rather than slathering a paint of pessimism or dreariness onto the characters, Chabon pitches a celebration of the era of their creation. Even though the Fantastic Four live in 1995, it is "always November 21, 1963. Men still wear hats, kids are into hot rods and spaceships, women have bouffant hairdos and New York City is the vibrant, shiny capital of the Free World. A Technicolor, bossa nova, Douglas Sirk world." Reading the early paragraphs of the pitch, you might initially think Chabon is suggesting a "non-time" reality, much like Tim Burton's mashing of the 1930s and 1980s in Batman. But that's not the case.

The premise of the story is that the Fantastic Four's world truly is today just not "our" today. The reality of the film is a present-day where the early '60s never ended. Soviet Communism remains a threat, and comic book style menaces such as alien invasions are present, but everyday life continues as it did before the nation's loss of innocence. It's Doctor Doom, while studying the timestream, who has discovered the existence of one human, a "key life" that's essential to maintaining the seemingly idyllic status quo.

As Chabon explains, Doom is "determined that the existence of one person set in motion the chain of events that have maintained the world as it is, or rather have prevented it from devolving into the dark, evil, scary place that it could be -- a place which, naturally, he would dominate with ease." With his Time Platform, Doom travels into the past to terminate this mystery person, and it's up to the Fantastic Four to stop him. Doom's machinations create a vision of this new world: "It's a frightening place where New York is covered in graffiti, children carry guns, the ozone layer is depleted, the Capitol is filled with corrupt, showboating demagogues, etc."

Who is this mystery figure responsible for saving the world from corruption? Well, Chabon never says. He pitches a few ideas. It could be a known public figure (JFK would seem to be an obvious choice, given the date Chabon cited earlier.) It might be Reed Richards. Or perhaps an anonymous person who unknowingly made a specific choice one day and created a butterfly effect that's influenced American society.

In the midst of the time travel adventure, Chabon has a character subplot involving Reed Richards and Sue Storm deciding whether to marry. Reed carries weight from his past, specifically an incident with Victor von Doom that burdens his conscience, while Sue feels that even more of her identity would be submerged in a marriage with Reed. Chabon draws inspiration from the John Byrne Fantastic Four comics, pitching ideas to translate the storyline that had the Invisible Girl discovering her true strength and becoming the Invisible Woman. And after finding her true self, she now has the confidence to join Reed as an equal in marriage.

Chabon seems reluctant to directly adapt the specifics of Byrne's story arc, opting for something more straightforward. Tying the concept in with the film's unique world, Chabon suggests having Sue kidnapped by Communist agents and used as a weapon against the heroes. The team must save itself, while also saving their retro-reality from becoming ours. As for the Thing and Human Torch, Chabon essentially says "they're around." Admittedly, it wasn't a detailed pitch and was mainly an attempt to establish the film's unique world. If the project had been pursued, Chabon would likely find more significant roles for the heroes.

FAN SERVICE

A movie written by a fan, as a tribute to the era of the team's creation. Yes, it's easy to see diehard Fantastic Four fans lining up for this movie.

NON-FAN SERVICE

One might argue that Chabon's entire pitch is predicated on the idea of the team being so rooted in a bygone era, a modern audience can't accept them without a forced application of nostalgia. The premise is also open about the characters not existing in our world, essentially conceding to a mainstream audience that superheroes are no different than any other fantasy material.

PULLED FROM THE SCRAPS

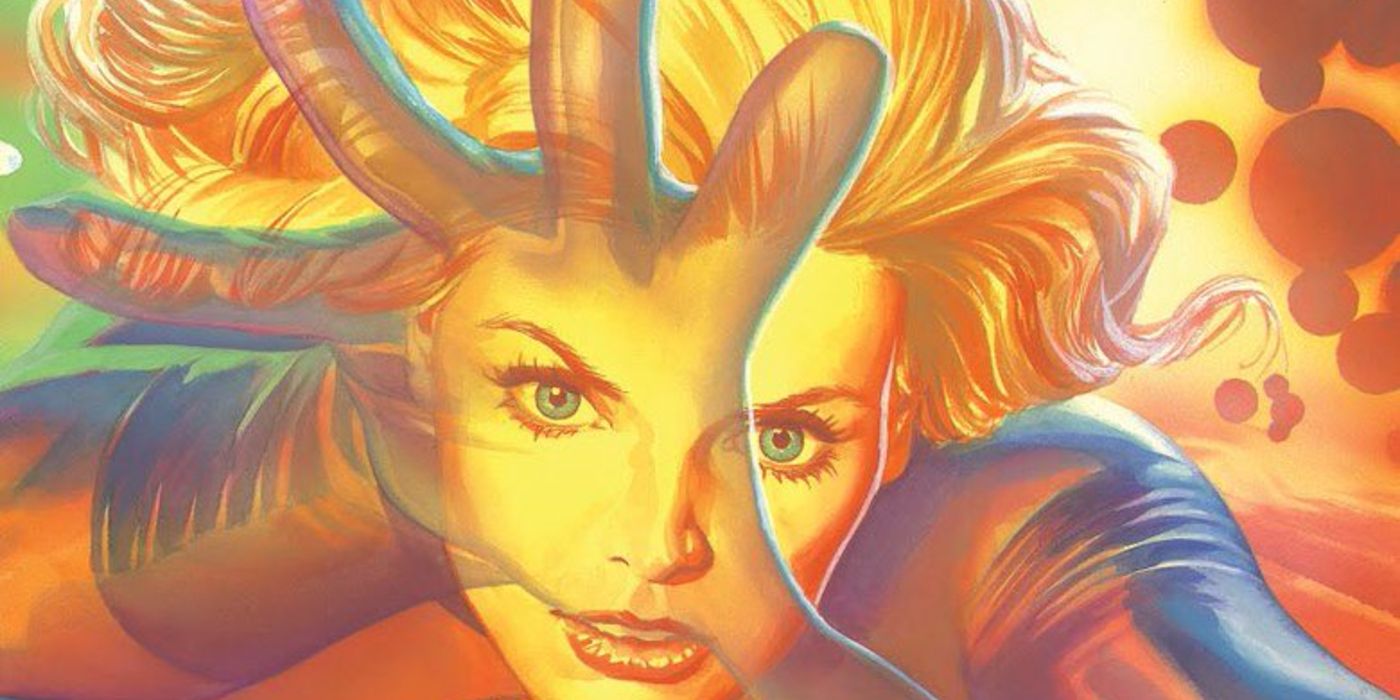

None of Chabon's concepts would later appear in any Fantastic Four film. However, Alex Ross did pitch a retro-themed reboot of the Fantastic Four comic a few years ago that would've also played heavily into the book's early '60s roots. He discussed his pitch and provided several pieces of original art in an issue of Back Issue magazine earlier this year.

DID WE DODGE A BULLET?

Oh, no. This could've gone off the rails under the wrong director, but the idea of a 1960s-inspired Fantastic Four film that uses nostalgia as an actual plot point is quite ingenious. Would 1990s audiences have bought this? Who knows. There really wasn't an exorbitant amount of nostalgia for this era by the '90s, to be honest, as the aesthetic of the time was based on irony, cynicism and "realness." Bouffant hairdos and fedoras were the least cool thing on earth at the time.

If anything, the story could easily take a Pleasantville turn, where we discover the innocent days of the past weren't so innocent, after all. It's also questionable if audiences would've bought the idea of the '90s as some horrific hellscape, as it's typically viewed as a period of peace and prosperity (even if mainstream entertainment had grown more cynical in this era).

But look at the actual Fantastic Four films. Two attempts at making the characters ultra-modern, while also leaning into the action-comedy genre. (To be fair, both were financial successes, but also despised by fans and critics.) Then, the gritty reboot that's one of the most disastrous flops in history. Apparently, the world wasn't ready to see the team act as black ops government agents. Who knew?

Chabon's right -- the team has "fantastic" in its name. Strictly applying reality to the concept robs it of the magic. Acknowledging the characters' roots while crafting an imaginative story feels far more interesting than distorting the concept to conform to the latest fads.

Hey, my latest paranormal novel Love is Dead(ly) is available for preorder right now for just ninety-nine cents! You can also check out a free preview chapter at this link.