With so many comic conventions occurring across North America and Europe, it is sometimes easy to forget that such events are still rather unusual in other parts of the world. And while they are spreading, the key to their success -- and that of sequential art around the globe -- is the way they open themselves up to reinvention in order to make themselves relevant to new cultures. This is certainly part of what the Middle East Film & Comic Con (MEFCC) has done, and why the event, now in its fourth year, has become such a tremendous success.

The Middle East got its first MEFCC con in 2012, and the even has been held annually in Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, widely viewed as one of the most liberal places in the Arab Middle East, ever since. In four short years, it has grown exponentially from something that could be held in a small hall owned by a yacht club (welcome to Dubai) to taking up three large halls at Dubai's massive World Trade Centre convention complex.

In 2012, there were no comic shops in the UAE -- now there are two; Comics Central in Jumeirah Lake Towers, and Comicave in the Outlet Mall. Dubai boasted a branch of the famously well-stocked Japanese bookstore Kinokuniya, but nowhere in the city, or even in the wider Gulf region, received regular comprehensive weekly comic deliveries, and that remains the case today. In terms of local comics culture, the biggest icon was "Majid," a very popular Arab-language anthology published by the UAE-government and backed Abu Dhabi Media. But "Majid" is aimed at children and focuses on one and two page humor strips rather than longer, ongoing narratives.

When the first comic con happened, no one quite knew what to expect. There were no tables of longboxed back issues, but plenty of graphic novels and manga. There were a few TV and film stars, and ever-ebullient screenwriter Max Landis, as well as publisher Archaia. What the exhibitors and guests soon discovered was an incredible interest in what they had to offer, be it comics, video games, manga, original art, prints, t-shirts, bags or opportunities to meet film and TV stars.

Moreover, what everyone discovered was a sense of community. The Middle East was, and in many ways still is, a market that has long been overlooked and underserved, but now it was finding its voice and it was providing a venue in which Dubai's overlapping multicultural populations could meet and share interests and experiences.

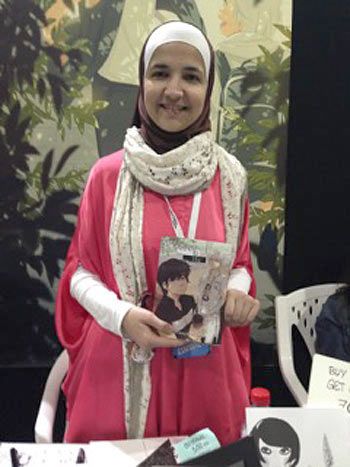

In the Artists' Alley of this year's MEFCC, you have Emiratis from the host country, but you also have Saudis, Kuwaitis and Bahrainis from the Gulf area, Egyptians, Jordanians, Sudanese and Syrians from the wider Arab Middle East, and from further afield, there are Indians and Pakistanis (both countries just three hour's flight away), Filipinas and Filipinos, Indonesians, Americans, South Africans, Brits -- the list goes on and on.

This different mix of nationalities and cultures helps give the MEFCC its very different flavor from what can often feel like the bland sameness of many North American cons. While there is an awareness and knowledge of superheroes at the MEFCC, much of this is filtered mainly through big screen adaptations. There also appears to be a greater level of manga literacy than there was an interest in the state of current DC Universe continuity.

This difference is also easily observed in the cosplay, which involves more body coverage at MEFCC, and often more imagination and artistry. You are less likely to see a scantily-clad Vampirella, but I spotted two women in abayas and sheylas rocking out as The Joker. In a region where there is recognizable and widespread formal attire of kanduras and abayas codified as "national dress," cosplay offers an exciting new avenue of self-expression. You'll want to be very careful about asking permission before taking a photograph in Dubai, but then, that is what you should do at any comic con anywhere in the world.

The importance of costume surfaced when chatting to people based in the region in artists' alley. While I didn't spot any Ms Marvels among the prints, there were a number of sketches of Batgirl, and her practical costume struck a chord with the women I spoke with who were drawing her.

Artistically, the most prominent influences on new comics from the region appears to be manga and anime, with themes of family, friendship, adventure, myth, tradition, travel, humour, fantasy and politics to the fore. Take, for example, the Saudi-produced original Arab-language manga anthology "Eesar," now in its third issue. The magazine is aimed squarely at both appreciating manga and the Japanese culture (with articles on Japanese cultural figures such as actor Takashi Kitano) that spawned it, but also in reinventing it for a regional audience. "Eesar" has now been running as long as the MEFCC, each issue thicker than the last and its slate of Saudi creators growing at the same rate.

For some, creating comics in Arabic is an important expression of cultural identity, but there are plenty who prefer to create strips in English. Enas Al-Shuwayer is a children's writer from eastern Saudi Arabia. Her graphic album, "The Legend of Shera," which emphasizes the importance of knowledge science and art, is written in English. It appears to draw influence from Herge's "Tintin," and the Herge influence is also visible in the work of the unaccredited artist.

Dee Juusan is a Jordanian writer-artist. There are no comic shops or comic conventions in her country, so the MEFCC provides her with an invaluable opportunity to meet new readers in person and introduce them to her ongoing slice-of-life original English-language manga about friendship. Her work is also available for free online at "Grey is." The strip has a lyrical quality to it not often seen in western comics, and has already achieved international recognition in Japan.

Khadija Al Saeedi's "What Happened in 1991?" is another English-language book, a fun post-apocalyptic time-travel tale with alien zombies. Her art draws clear inspiration from the work of Bryan Lee O'Malley, but as far as the plot is concerned, the reader is left aching to know "What Happened in 1991?"

More seriously, there is "Team Muhafiz" by Imran Azhar, Roy Soumyadipta and Babrus Khan, about a multi-ethnic group of teenagers from Pakistan who work together to revive their local youth centre and fight sectarianism and other social ills. Think X-Men, but without the super-powers.

Or, there is the day-in-the-life "Mithosology," the comic strip diary of Emirati Nayef Al Blooshi. A video game designer based in Abu Dhabi, his work reveals how local film translators' use of the same Arabic word for "curse" and a particular "curse word" made the Disney movie "Maleficent" seem a lot ruder than its makers had intended.

And then there were the illustrators who created prints of the show's major guests for the star to sign -- Gillian Anderson was a favorite for this, although the "X-Files" actress was at first a little surprised to see people regularly bringing Maryem Al Zaabi's print of her to sign.

So, how do you do a comic con in a Muslim country? It's pretty much like a comic con anywhere else. There are comics and cosplay, along with great creativity and enthusiasm. You'll find stories with a different flavor from those that dominate so many comic cons in the West, and experiences that will take you to a different place, a place of new ideas and shared community. And isn't that what comics, and comic cons, are all about?