I had been thinking of Maurice Sendak a lot lately even before his death was announced. That's partly because he'd been in the news a lot in the past year with the release of his book Bumble-Ardy. But it's also because I tend to think a lot about children's books in general and the way they often tend to crossover with comics.

Let me put it this way: Sendak was, of course, many things: an artist, writer, designer and all-around genius. But above all, Sendak was a cartoonist and the comics informed a good deal, if not most, of his work.

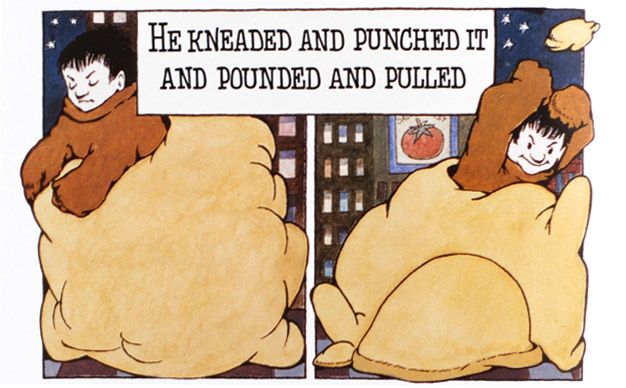

Certainly Sendak was no stranger to comics. The most famous example would be In the Night Kitchen, his heartfelt ode to Winsor McKay's Little Nemo. This is Sendak at his most comic-booky, and it's thrilling to see him depict motion in this manner -- the way Mickey tumbles and falls through space, the thin, three-panel page where he jumps into the bread dough against a static background, the arc the repeated images of Mickey and his plane make as they head towards the top of the milk bottle. You can call Kitchen a picture book all you like, but what it's really just straight-up, marvelous comics.

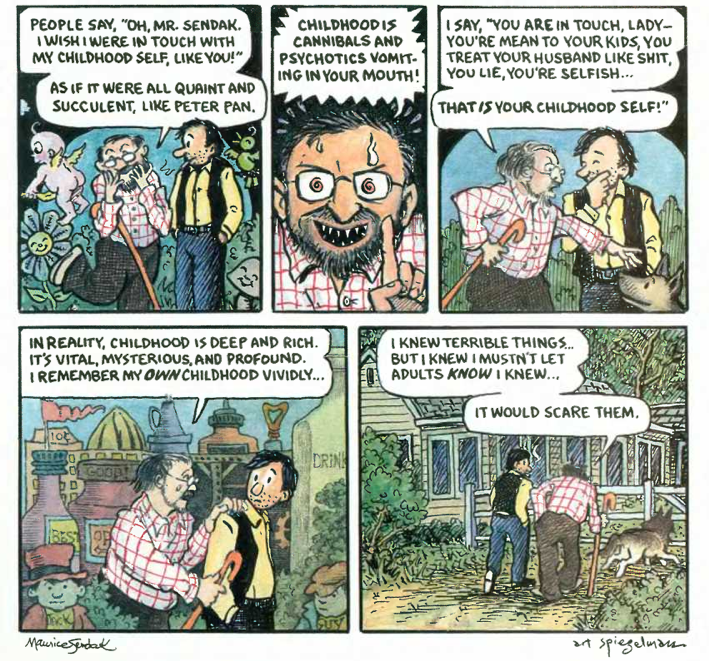

There are lots of other examples, too. His New Yorker collaboration with Art Spiegelman, comes to mind naturally, but there's also Cereal Baby Keller, his contribution to the second Little Lit collection (ever notice how many of Sendak's stories involve food and consumption, especially the eating of one's parents?) There's also the little-known Some Swell Pup, a lengthy comic about the hazards of being a pet owner. Higglety Pigglety Pop! ends with a brief nursery rhyme turned into a 14-page comic. Even the pop-up book Mommy incorporates many comic idioms.

Even look at Sendak's most famous book, Where the Wild Things Are. While perhaps not literally comics in the way most of us define the medium, the design and composition clearly shows just how powerful an influence the Sunday funnies exerted on Sendak. Look, for instance at the way the forest slowly grows out of Max's room over several pages. Look at how the images (I won't call them panels for fear of offending purists) start small and slowly grow until Max's imagination comes into full bloom. Look at the silent sequence in the middle of the book with Max and the Wild Things partying. Note especially the composition of those pages, how your eye moves across the page, but pauses at wherever Max is. Sendak may have worked in the more rarified world of children's literature, but it seems clear to me at least that his heart rested with the ink slingers that told stories in the daily newspapers and ten-cent magazines.

I'm always kind of amazed that more contemporary cartoonists don't consciously draw on children's authors.The industry is filled with people essentially making comics for the very young -- William Steig, Mo Willems, Shel Silverstein, David Weisner, Marc Rosenthal and Brian Selznick to name just a few. While there's a fine line between children's picture books and comics, the two share many similarities. And yet for some reason we tend to place a strict divider between the two worlds.

More than anyone else, I think Sendak leapt back and forth over that wall frequently. More significantly, I think he showed both children's authors and those making more traditional comics ways to improve and enrich their storytelling capabilities. Aspiring artists would do well to not just admire Sendak, but closely examine his work and use it as a map to finding their own inner wild thing.