So have you heard there's a new Superman movie out? It's mostly playing in small art-house theaters with a minimal marketing budget, so you might've totally missed it. You should check it out.

If you haven't seen it, fair warning: Here there be spoilers.

This isn't a review because, honestly, you've probably already made up your mind. However, it is a look at how the changes to the Superman mythos made in Man of Steel have altered the origin, and indeed the character, intrinsically.

A lot of these observations were inspired by a podcast discussion of the movie at Part-Time Fanboy, in which host Kristian Horn caught on to something that hadn't really stood out to me on my first viewing (the episode was recorded earlier in the week and should be available today). Since the recording, I've been thinking about what he said, and the more I think about it, the more I see how it seriously alters Clark Kent, and may in fact be the root of my problems with the Man of Steel.

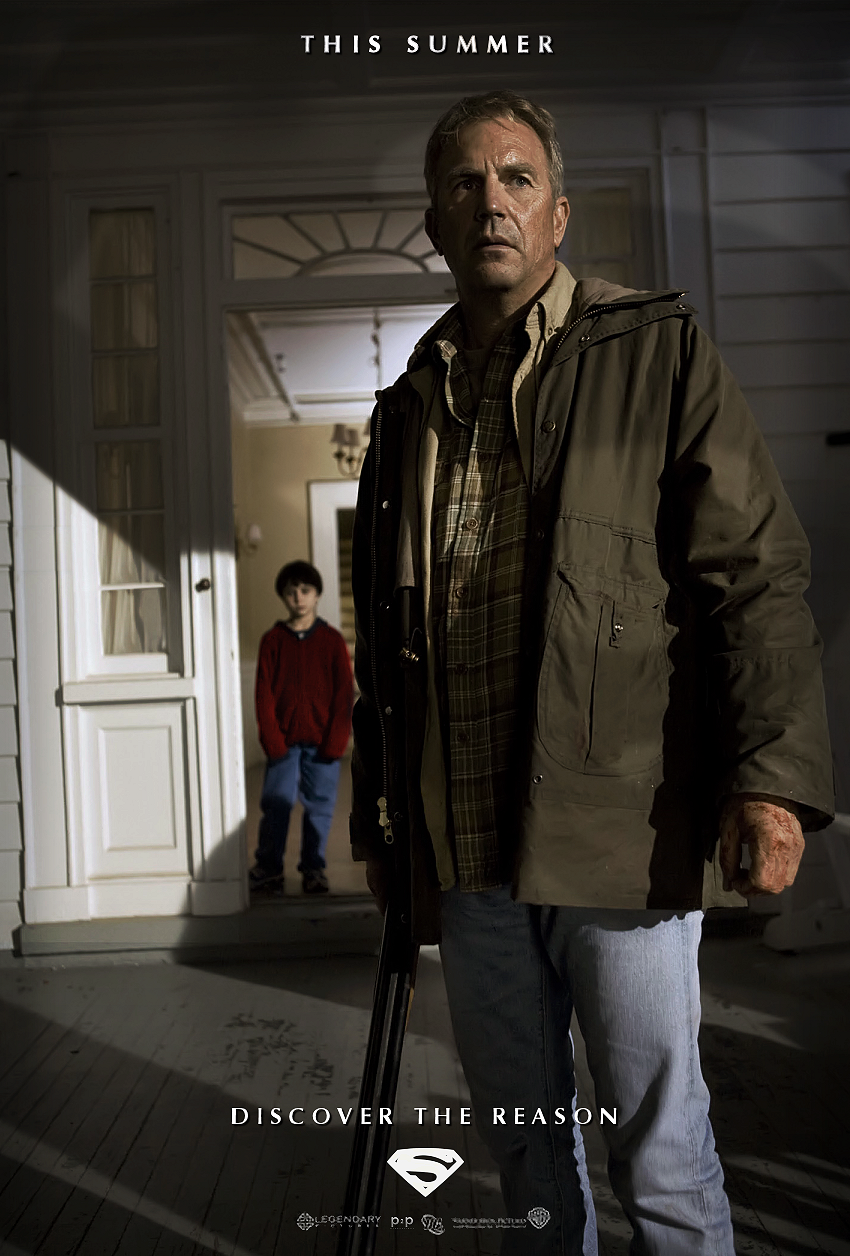

Most people just looking for an exciting movie or a badass Superman enjoyed Man of Steel, and there is plenty to like: There's some excellent design, particularly of Krypton, the bar has been raised on super-person battles, and most of the acting is fine to actually quite good; Kevin Costner's delivery of the line "You are my son," despite being over-used in trailers, choked me up.

Complaints usually focus on the last act, which comprised mostly of excessive and protracted fight scenes between combatants surprisingly oblivious to the destruction and mostly off-screen death around them, and more so the death of Zod at the hands of Superman. Those were my biggest problems, too, until the recording with Horn, who focused on an earlier scene that disrupted the movie for him (listen to the episode because he tells a beautiful and very personal story of why Superman means so much to him).

I'm building up to the tornado scene, which ends with the death of Jonathan Kent due to Clark's inaction at his adoptive father's insistence. Clark obeying at that moment, and allowing his own father to die fundamentally changes his motivation as a hero. Like Bruce Wayne and Peter Parker, Clark Kent's decision to use his abilities to help people is now inspired by guilt over death. In all three instances, each character blames himself for the death of his parent(s) or parent figure. Previously, Clark was motivated to become Superman out of a desire to help people because of the moral guidance he received from his rural upbringing.

Not only is Jonathan and Martha Kent's parentage less intrinsic to the mythology of Superman, Jonathan actively discourages Clark from helping people. Most parents live in fear that their kids somehow will be hurt by the world, and an urge to protect and even shelter them is common. So Jonathan's "maybe" response to Clark's question of whether he should've let his classmates die in a school bus accident is difficult, but most parents will probably relate to it on some level. That creative decision might be more realistic, but that doesn't mean it's the right choice for a superhero/science-fiction story. This means Clark has to find a reason to be a hero from somewhere else, and this is where things get messy.

The filmmakers' solution is that he's motivated by guilt to roam the world secretly helping people until the arrival of General Zod compels him to go public. (This conveniently happens right after the Lois Lane story he's conveniently investigating leads him to a ship that conveniently explains his Krypton lineage so he's prepared when Zod shows up.) The problem is that the guilt motivation isn't quite the impetus it's set up to be: Clark is already instinctively helping people as a young boy; he does so on a number of occasions, we're told -- so much so that one neighbor challenges the Kents about their mysterious son, which they dismiss with folksy country charm. So Clark didn't receive his moral drive to help people from Jonathan Kent, or from guilt over his death. And it certainly wasn't from Martha, although she does help him focus and control his super-senses. It's not from Jor-El, either. By the time Clark "meets" him, he's already been covertly saving people for some time. So where did it come from? Why does Clark feel the need to help people?

The only explanation left, given what we're shown and told, is that there is something within Clark that compels him. It's a core element of his character. It's not nurture, it's nature -- it's something genetic. And as we know, Clark is genetically Kryptonian, the first in centuries to be born naturally. Unlike Zod and his army, and even Clark's biological parents, he wasn't born from those strange baby pods, which somehow tinker with each baby's genetic makeup to sculpt them for a needed job. Instead, Clark was able to be born on his own and decide his own interests and fate -- and ultimately the naturally born and naturally raised Clark defeats the unnaturally born and raised Kryptonians. Nature defeats science. It's also worth noting that Krypton was destroyed because of the unfettered technological consumption and leeching of the planet. For a science-fiction movie, this is a surprisingly anti-science or anti-technology stance to take.

It doesn't all quite work, though. Despite his Kryptonian heritage being the source of his heroic drive, he rejects it. "Krypton had its chance," he finally says to Zod's repeated appeals for an alliance. He hardly hesitates in destroying the few links to his home planet and family, including that old colonizing ship he found earlier that answered so many questions for him. He chooses Earth by turning himself over to Zod and helping to stop hiss plans.

Another spanner in the works is that Clark's birth wasn't quite as natural as Jor-El intended. Almost immediately after Kal-El is born, his father implants him with a DNA database of every Kryptonian using the codex. What influence does that have on Clark's genetic makeup? Does it influence his personality, his goals?

Muddying the waters further is Clark's lapse in his ingrained concern for life during the climactic battle through Metropolis, and to a lesser extent in Smallville. Screenwriter David Goyer admitted that "clearly hundreds if not thousands of people" died while the gravity machines were running. An expert estimate places the initial death toll of the entire Metropolis battle at 129,000 with a 250,000 more missing (likely a portion of that number adding to the dead over time) and 1 million injured (again with some of those probably dying later from injuries). That is a lot of people, and his careless crashing through skyscrapers and tearing up the city absolutely contributed to that total. Was it due to Superman's inexperience, or did he get caught up in fighting? Not once did he make an effort to move the battle to a less-populated area. Even if Zod were to direct it back to Metropolis, doesn't a hero try?

So if it's not a nature over nurture influence guiding his choices to save life, maybe it's more about free will. By letting Clark be born outside of those Kryptonian birthing chambers, he's given the choice to decide his own fate, something the citizens of Krypton gave up centuries ago. This promotes a message that giving people free will results in them picking the right and just path, as opposed to Zod's programming, which corrupts and ultimately destroys him. Of course, that still doesn't explain the above lapse: If Clark chose freely to ignore saving lives, maybe it's not so good after all.

In the end, we're left with no clear source for what drives Clark to live up to the high expectations put upon him by both fathers, and perhaps that is why he fails to live up to them, and why ultimately the movie ends as a bit of a downer. We're continually reminded that he is a symbol of hope -- he is literally labeled as "Hope." We're told he will be like a god, that he will be something for which humans will strive, that he will be an example. And what does this shining paragon of heroism do? He steals and he kills.

Is Superman false hope? Perfect characters are boring, so I don't mind a flawed hero. But shifting the source of Clark's motivation, whether it's mimicking the guilt of Batman, some kind of statement about nature vs. nurture or about free will, all it accomplished was weakening the character's perspective. This makes it easier for his concern for life to be put on hold for the sake of a more flashy battle. This inconsistency is why the third act falls apart for those who didn't love the movie.

Every version of Superman influences other versions in comics and other media, but I hope this take on Superman's origin remains unique to Man of Steel and its inevitable sequels.