I have a confession to make. I don't read comics to find out what happens next. I usually don't really care what happens next, to be honest. I care how it happens. The "how" is the most interesting aspect of any medium. And while fans of the Madman character might really care what kind of trouble Frank Einstein gets himself into with each issue, I have a hard time believing that those kinds of readers are satisfied with any recent issue of "Madman Atomic Comics." Because, as a creator, Allred seems less and less interested in the "what" and more and more interested in the "how" of his comic book stories. His use of formal experimentation has exploded in this series, especially compared to his earlier work on "Madman."

A quick flip through the immense "Madman Gargantua" volume will show how far Allred has come as an artist. His compositions and line work advanced exponentially from "Madman" through "Madman Adventures" and into his mature phase with "Madman Comics." But the issues of "Madman Comics" were remarkably consistent from issue to issue, as if his talent reached a plateau. You might be able to distinguish a later issue from an earlier issue purely by the interior art, but it would be difficult. It all looked gorgeous, but remarkably consistent for an artist who had improved so drastically between series.

Apparently, since Allred had settled into a comfortable style with his character designs and poses, he decided, before embarking on "Madman Atomic Comics," to turn his attention to developing new stylistic tricks between panels. It's almost as if he said to himself, "okay, I can really make the panels look the way I want now. What can I do to play around with the conventions of storytelling? How can I affect the story by altering the relationships between the panels?" Let's be honest: in the first nine issue of "Madman Atomic Comics," Allred has given us very little in the way of story. Almost nothing has happened, except for a long, ponderous journey through space and/or comic book history. And then he found out the two girls in his life were actually the same girl. Or something. It doesn't really matter. What matters is the formal experimentation Allred has used, giving each issue a unique flair, and a unique approach to storytelling (not necessarily unique in the medium, but unique in terms of other Madman stories).

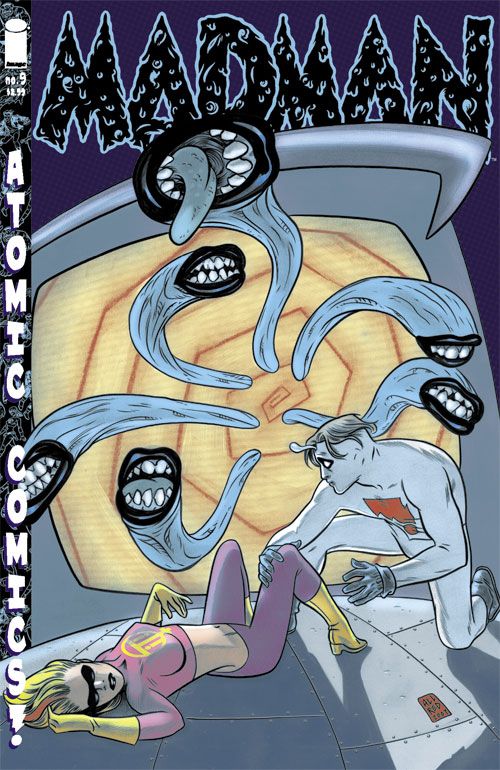

One earlier issue had Allred drawing each panel in the style of a significant comic book artist from the past. Another issue was totally silent. And this issue, "Madman Atomic Comics" #9, is drawn as basically one single panorama, sliced up into 14 double-page spreads. If you bought two copies of this issue, and pulled out all the pages, and placed the spreads side-by side, you'd get one long city street. And the "plot" of this issue, such as it is, deals with a gaggle of "flying, fishy-lipped beasts" zooming down the street with Frank Einstein's love, It-Girl, in their jaws. The Atomics, local superheroes and former zombie beatniks, help Madman rescue her. That's it: fourteen panels of the heroes trying to get the girl away from the slimy floating things.

But what Allred accomplishes here is amazing. Comic book artists rely on panel size and panel placement to control tempo and to create a sense of spatial movement. Allred does it all with just the double-page spreads. Yet he still makes this comic feel full of energy and motion. He's using layout and composition within each double page spread to simulate action, and it works magnificently. When the chase finally comes to an end, Allred gives you a sense that the narrative brakes have been applied, just by the way he poses the figures within the final two spreads. This is the type of comic that will be studied by artists for years to come, whenever they want to learn how to use composition to create motion. It's formal experimentation that serves the story, and even if the story is overly simplistic, the success of the experimentation is worth the cover price alone.

Allred doesn't just provide a chase scene, of course, although that is the overt plot. He also provides a series of captions detailing Madman's inner monologue. And like every other Madman story ever written by Allred, this issue is really about one idea: identity. "Who am I and why am I here?" That philosophical question underlies all of Allred's stories and, in this issue, Madman questions everything he does -- his actions toward the monster, his relationship with the other heroes, his relationship with the universe. "Maybe you were meant to suffer," thinks Madman, tragic-heroically, as the story comes to a close.

"Madman Atomic Comics" #9 isn't for everybody, but if you're at all interested in an artist trying to push the boundaries of the superhero genre, an artist trying to use the conventions of the comic book form to its utmost, then you need to take a look at what Allred is doing here. It's all about the "how."