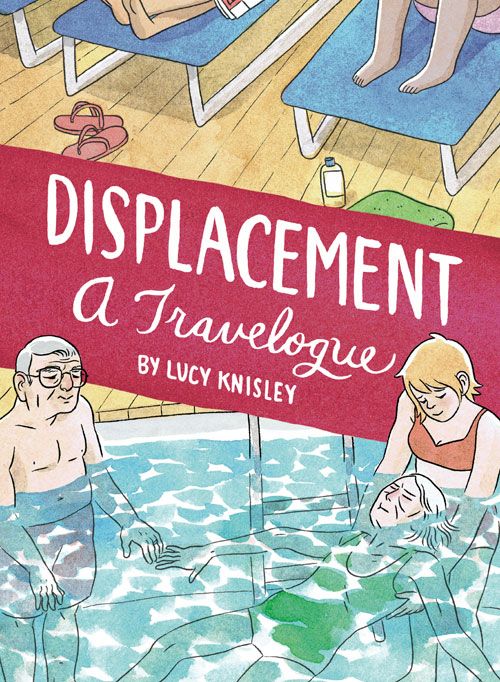

Each of Lucy Knisley's memoirs has been stronger than the last, and Displacement continues that rising arc. While An Age of License, her story of a trip through Europe, was sort of a free-range travelogue, Displacement, her account of a cruise she took with her elderly grandparents, is more introspective and self-contained.

I can't claim this is an original insight; Knisley lays it all out on one page of Displacement, where she recalls the trip that became An Age of License. "That trip was about independence, sex, youth, and adventure," she muses. "This trip is about patience, care, mortality, respect, sympathy, and love."

Indeed, where An Age of License is filled with drawings of interesting places and fabulous food, Displacement focuses tightly on Knisley and her grandparents. Traveling on a cruise ship is all about the journey, not the destination; Knisley only gets off the ship for two short excursions, and even then, she is less interested in local color than the people around her. While she started every chapter of An Age of License with a drawing of her journey to the next destination, she starts each chapter of Displacement with an image of the empty ocean, with the horizon getting higher with each day of the trip.

Knisley's true journey is not across the water but into the land of the aging, and good traveler that she is, she adapts amazingly well. There's a page when she makes explicit a transition that many of us are familiar with: Her grandmother, who is suffering from dementia, is upset because she thinks Lucy thinks she has stolen something. Lucy flashes back to her 7-year-old self, being scolded by her grandmother, and then straightens her back and takes charge, flipping the roles in a way that will ring true to anyone who has taken care of an older relative.

And, having been in that situation myself, I'm impressed with how well Knisley handles it. Her reflexive pose is to shield and care for her grandparents. When her grandfather "has an accident" in the airport, she doesn't recoil — she's too busy looking daggers at the passerby who is making a face at them. She's patient with her grandparents and attentive to their needs, but she also admits to her feelings of frustration and insecurity, as well as her horror at what's happening to her grandparents as they age. As a counterpoint to the story of their frailty, Knisley includes passages from her grandfather's memoir of his experiences as a pilot during World War II—and immediately after the war, when he married her grandmother. These stories really round out the picture and bring her grandparents into clearer focus.

Knisley's draws with a sure and deceptively simple line, and she breaks up each page differently, using a variety of different layouts depending on the situation. She makes it look easy, and in some ways this is an easy book to read, even if the message is difficult to accept. Although her style is visually appealing, Knisley has some harsh things to say—about herself, her family, and some of the people they encounter—and she doesn't shy away from depicting the uncomfortable aspects of caring for her grandparents. As Roz Chast did with her parents in Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, Knisley paints a true portrait of old age, never denying the unpleasant realities of illness and dementia but never letting her grandparents dwindle to just that. They remain strong personalities in their own right, and through flashbacks and her grandfather's memoir, Knisley pays tribute to them by telling their story as well as her own.