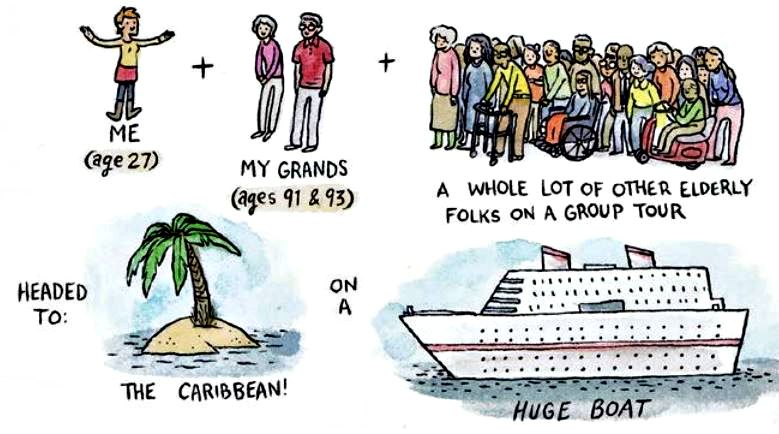

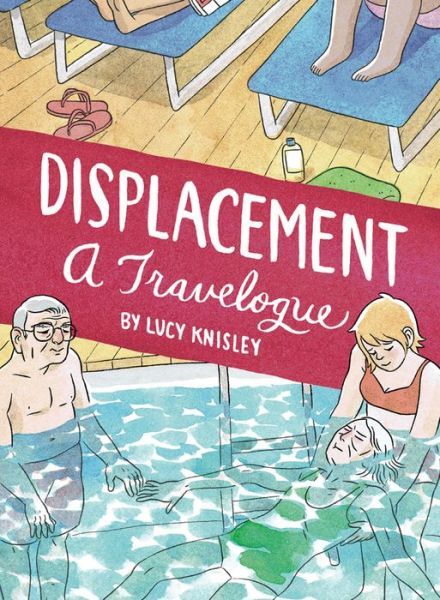

At first glance, you might expect Lucy Knisley's latest travelogue Displacement to be filled with the same humor and insight as her previous books Relish: My Life in the Kitchen and An Age of License. After all, it recounts the 2012 cruise with her memory-impaired 91-year-old grandmother and physically challenged 93-year-old grandfather. Yet the quality that's made Knisley a great storyteller -- her ability to recall nuanced encounters with a blend of wit and compassion -- allows her to craft a compelling and complicated account of this time spent with her grandparents.

If Knisley had structured Displacement as a daily diary of the trip, it wouldn't be the must-read that is is. Instead, she inserts excerpts of her grandfather's World War II memoir, which she would reread in the evening (after getting her grandparents to bed) in her windowless cabin.

It was amazing to learn that her grandfather, who served as a liaison plane pilot, had to accept that one of his fellow soldiers may have drunkenly butchered a Frenchman near the camp ("... but he denied it, and I had no proof"). To the other extreme, he delighted in recalling when he practiced takeoffs and landings in England. ("The famous Stonehenge monument at that time was not commercialized or protected by fences. Thus I could land and taxi right up to it!")

At one point Knisley confesses, "I never really clicked with my grandmother, though I still love her." Yet during the cruise, despite the fact her grandmother no longer consistently knew Knisley was her granddaughter, they were able to connect -- and her grandmother to relax -- when they swam in a small pool. This interview provided an opportunity for me to discuss balancing the elements of her latest travelogue, and to find out whether Knisley's recent honeymoon will be future memoir fodder.

Tim O'Shea: When you embarked on this trip with your grandparents, did your family always know you might turn the experience into a graphic novel?

Lucy Knisley: Yes, they're aware of what I do, and I explained that I'd be writing about the trip. I have a very understanding and supportive family, thankfully.

How did your father react to your candid assessment of him? Did you let the members of your family portrayed read it before it was published?

He was happier with this depiction than he has been with others. My parents are very proud of me, and proud of my honesty. I try to tread lightly, and ask permission before I include other people in my stories, and as I said, I'm very lucky to have a supportive family. I sent a PDF of the book to my aunts and uncles, and it was met with mostly sympathy -- we're all experiencing similarly trying moments with my grands, and it can be good to share those experiences with one another.

One aspect of the book that I think would resonate with readers on different levels: the fact that due to eyesight issues (in the case of your grandfather) and memory issues (with your grandmother) reading no longer was feasible. Was that an aspect you always knew you would broach in Displacement, or was that something you realized needed to be explored in the evolution of the final work?

I come from a very bookish family: My grandparents were both teachers, as is my father. We all love to read, and it always seemed like my grandparents would enjoy their retirement, as long as they could still spend it reading. But now that their health is failing them to the point that they're unable to read, it's heartbreaking. The book is really a series of attempts at connection, and discussing the loss of that connection -- this shared love and activity -- and the loss of this intrinsic part of them, was a big part of that missing connection.

In terms of your personal satisfaction, what pleases you more, that you shone a light on the ravages of aging on your loved ones in a candid yet somewhat-hopeful manner or that your grandfather's memoirs found a much wider audience thanks to your inclusion of excerpts from it in your book?

My reasons for the inclusion of my grandfather's memoir was twofold:

1. I wanted to underscore the significance of him as a storyteller, rather than a character in someone else's story, as so often happens in memoir. It's difficult to see our loved ones lose their faculties, becoming characters in their own lives. I wanted to draw a parallel between myself as a storyteller, and my grandfather as a storyteller.

2. My grandparents, while they might not remember last week, remember parts of the war with extreme clarity. I wanted to reread his war stories and probe them for more details from the stories -- giving us a chance to talk about this time that was so important to them, and giving me a chance to better understand the way their memory works around this period of their lives.

Given that you graphically portrayed you and your grandparents throughout the book, what prompted you to include the photo that you three took on the boat?

I've always been fascinated with utilizing photography in memoir. Comics are a very controlling way to tell a story, dictating how things are remembered both through the writing and through visual memory. But all stories are subjective, and I love it when a true story is corroborated with a photo, as I feel it takes readers to another level, where they are realizing the subjectivity of the storyteller, when confronted with the camera's version of the truth. I use photos in almost all of my autobiographical stories, and for this one I thought I'd include the photo that we took aboard the ship, following the story of how we had the photo taken. It's one thing to see my drawings of how I see my grandparents, and another to see them for yourself, and imagine yourself as a person observing this story in the moment. We all see our loved ones through our own lenses, but a photo can tell many further stories to the viewer; my grandmother's brittle smile, my grandfather's squinting eyes, my determined and slightly desperate expression -- it's bridges this divide between the emotional immediacy of my own drawings of the event, and the harsh reality of what was happening. In effect, I become a character written by the camera, much in the way my grandfather bounces between being a storyteller of his war memoir, and the subject of my travelogue.

How did you arrive at the chapter dividers (the book breaks down into days of the trips as chapters) being portrayed as an increasing depth of the waves over the course of the days?

Displacement is both a nautical term (concerning the weight of a ship that displaces the water) and a term that could be applied to my grandparents' necessary removal from their comfortable environment in Ohio to an assisted living facility in Connecticut, as well as their strange displacement to a Caribbean cruise. The chapter markers depict water rising to represent the increasing weight of panic or sadness at the realization of my grandparents' decline, as well as their own fatigue as time wears on.

In terms of the many challenging moments of the trip, what proved the hardest part for you to recount in Displacement?

The disembarkation day was one of the longest in my life, and it shows in the book -- it's the longest chapter. My grandparents were simultaneously falling apart physically, and I was completely losing my mind trying to get these people I love off a ship and aboard two airplanes, while they were having asthma attacks and vomiting. That was a rough day to relive.

You just came back from your honeymoon. Any chance you might do a travelogue of the honeymoon? Do you envision there would ever be a topic within the confines of a marriage that your husband might ask you to not document -- or that you yourself might not want to use?

I'm absolutely not doing a travelogue about the honeymoon. It was the first trip I'd taken in ages during which I didn't travelogue or work! It was great. My husband knew what he was getting into with me, and he's very happy and supportive when I include him in my work. But he also trusts me to curate these stories, and knows that there are boundaries I wouldn't cross, simply due to the nature of my work and interests. While I love erotic comics by others, it's not something that I'm particularly compelled to do, these days, so his privates are safe for now!

Are there ever moments in your life, when an experience is in the midst of unfolding, that you find yourself mentally envisioning how you might want to recount it the narrative form?

Yes definitely. I think this is a muscle that becomes both stronger and more easy to navigate as you get older and make more autobiographical work. It's no longer a hindrance from experiencing something, to make note of it for a comic later. When I was younger, it used to obliterate my own experience of an event, to try to mold it into a comic, but now I can let it wash over me and make note of it without being hobbled. Like most things, it just takes time and practice and patience.