Cleveland is the city where Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created Superman (and thus the very concept of the comic book superhero). It’s the city where Harvey Pekar spent his life and wrote his comics, including the recently, posthumously published valentine to his hometown, Harvey Pekar’s Cleveland. It gave the world writers Brian Michael Bendis and Brian K. Vaughn (we’re sorry and/or you’re welcome, depending on how you feel about those guys), and they even filmed the climax of a recently released and rather popular superhero summer movie there.

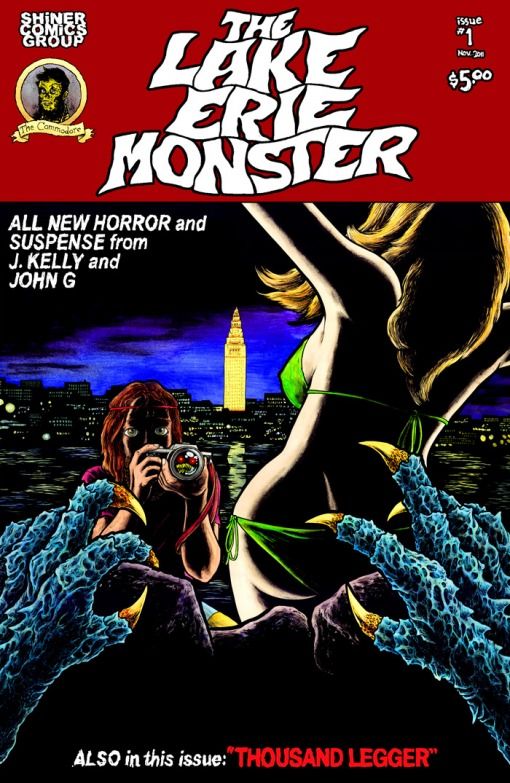

And here’s something else the city has going for it at the moment. It’s also home to Jake Kelly, John G and their self-published quarterly local horror anthology, The Lake Erie Monster.

Like most lakes of a certain size, Lake Erie has hosted reports of marine monsters over the decades, although sightings of lake serpents are much fewer, farther between and less credible than reports from, say, Lake Champlain (That didn’t stop Cleveland’s American Hockey League team from taking the name The Lake Erie Monsters, or The Great Lakes Brewing Company from naming a seasonal ale after one of 'em, though).

The comic takes its name from the first of its stories, which features a smaller, less serpentine monster that dwells in the lake, however.

After an introduction by a punning, Cryptkeeper-like horror host character who calls himself The Commodore, and who resembles a red-eyed, rotting corpse version of Commodore Oliver Hazard “Don’t Give Up The Ship” Perry, Kelly and G. present the first part of the “The Lake Erie Monster,” a story created to go along with one of the ten imaginary movie posters they had previously created.

It’s set in 1973, a few years after The Cuyahoga River famously caught fire and the year after Mayor Ralph Perk accidentally set his own hair on fire (Only the first incident had anything to do with water pollution, although I suppose the argument could be made that there was something in the water Perk was drinking that lead to that occurrence).

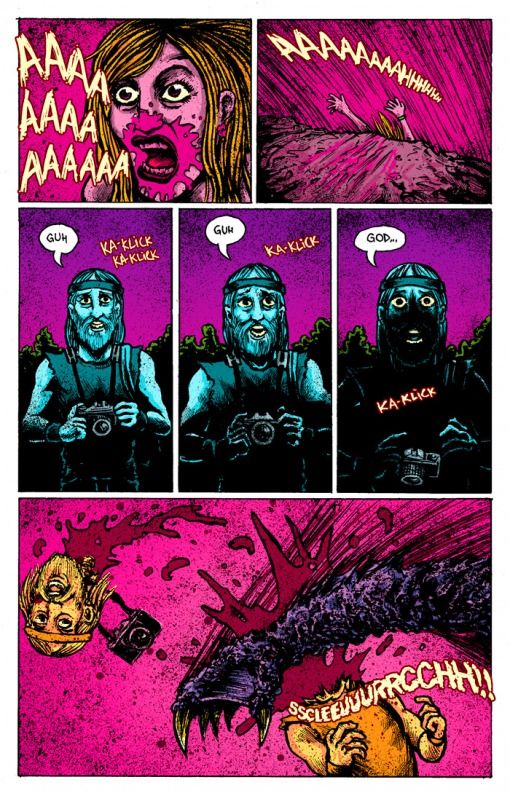

It opens with a pair of guys disposing of barrels of toxic waste by dumping them in Lake Erie, which may have something to do with the arrival of a big, murderous monster rising from the waters to take the lives of two folks in the wrong place at the wrong time (We only see the monster’s scaly arms and sharp claws in this first chapter).

Meanwhile, two reporters are draining beers in a bar instead of looking into the reports of mutilated animals being found along the lake, and the friends of one of the missing kids investigate their disappearance, finding grisly evidence of how they met their end.

There’s an incredible tactile aspect to John G's artwork, which compliments the homemade look and feel of the production, as it evokes 1980s black and white indie comics (although it is in color) moreso than more modern productions—appropriate, given the setting. The ink lines are thick, and the panels are dark with them, dots of ink dappling the sky, walls and waves. There’s texture to the art, and the metal oil drums and pavement look like oil drums and pavement feel.

The second half of the book is devoted to the standalone story “Thousand Legger” by Kelly, and refers to the limbs of a giant—like, alligator-sized—centipede creature that a young, wheelchair-bound man discovers at the foot of his bed one night.

The tense story tracks his battle with the creature, which has poisonous, stinging tendrils, and ends with a wonderful, insidious sting of an ending.

Kelly’s art is slightly smoother and less gritty than G’s, but their sense of design, detail and general aesthetic are highly compatible. This story uses a much more limited color palette, all black and orange during the daytime scenes that bookend it, and all light blue and black during the nighttime scene in which man and thing do battle. The earlier nighttime scenes, in which blackness overtakes the blues, remind me of Charles Burns’ art a bit, which is a good thing for any modern horror comic to be able to evoke.

The Commodore returns for a letters page editorial, and a one-page strip called “The Commodore’s Cleveland,” dedicated to the true-ish story of “The Treman of Train Avenue”:

In ’49, hobos, stewbums and drifters began turning up dead all over the place…and I do mean all over the place! Body parts would be strewn across the road, the tracks and the hanging from trees.

The Commodore tells us a witness said the murderer was a seven-foot-tall, red-eyed monster, but the killing suddenly stopped. Prompting the theory that the monster was itself a hobo of sorts, riding the rails—perhaps by accident—from Portage County, one the state’s hottest Bigfoot sightings sites.

I expect this will be a recurring feature, given the number and strength of The Commodore's Cleveland Clippings you can find on the book's companion blog.

The Lake Erie Monster contains plenty of ads (which occur between stories, rather than interrupting them), but these too are written and drawn by the two creators, and for Cleveland businesses, some of which distribute the comic. Even if you’re nowhere near Cleveland and are thus unlikely to see a show at the Beachland Ballroom or have a gourmet grilled cheese sandwich at Melt, many of these are fun in their adherence to old school comics ad format, like a Charles Atlas-style one promoting a comic shop (“Listen up, dude. You’re not ready for this level of geekiness. Go back to math class”) or several broken up into a dozen little squares of the Send away for these X-Ray Glasses, Sea Monkeys, nunchuks and, I don’t know, a live monkey type.

If you don’t live in or around Cleveland, you can order a copy of The Lake Erie Monster online here. If you do live in or around Cleveland, then you can probably find a copy at one of these fine establishments...and, while I'm sure you don't hear this too terribly often, you should also count yourself lucky.