More Holmesian goodness? Let's find out!

One of the interesting things about Holmesiana, something which I believe our own Greg H. has written of before (and if he hasn't ... he should!), is that even back when the original stories were still fresh in everyone's mind, other variations on Holmes were being presented by completely different authors.

The "last" Holmes story, "The Final Problem," appeared in December 1893, but Conan Doyle allowed William Gillette, and American actor, to take the scraps of a play he (Conan Doyle) had been working on and create a brand-new Holmes adventure, written entirely by Gillette, which debuted in October 1899. It would not be until 1903 that Conan Doyle himself brought back Holmes from the dead, as it were. So he was franchising out the character even before he himself was done with him (although, of course, he really wanted to be done with Holmes, but the damned public wouldn't allow it!).

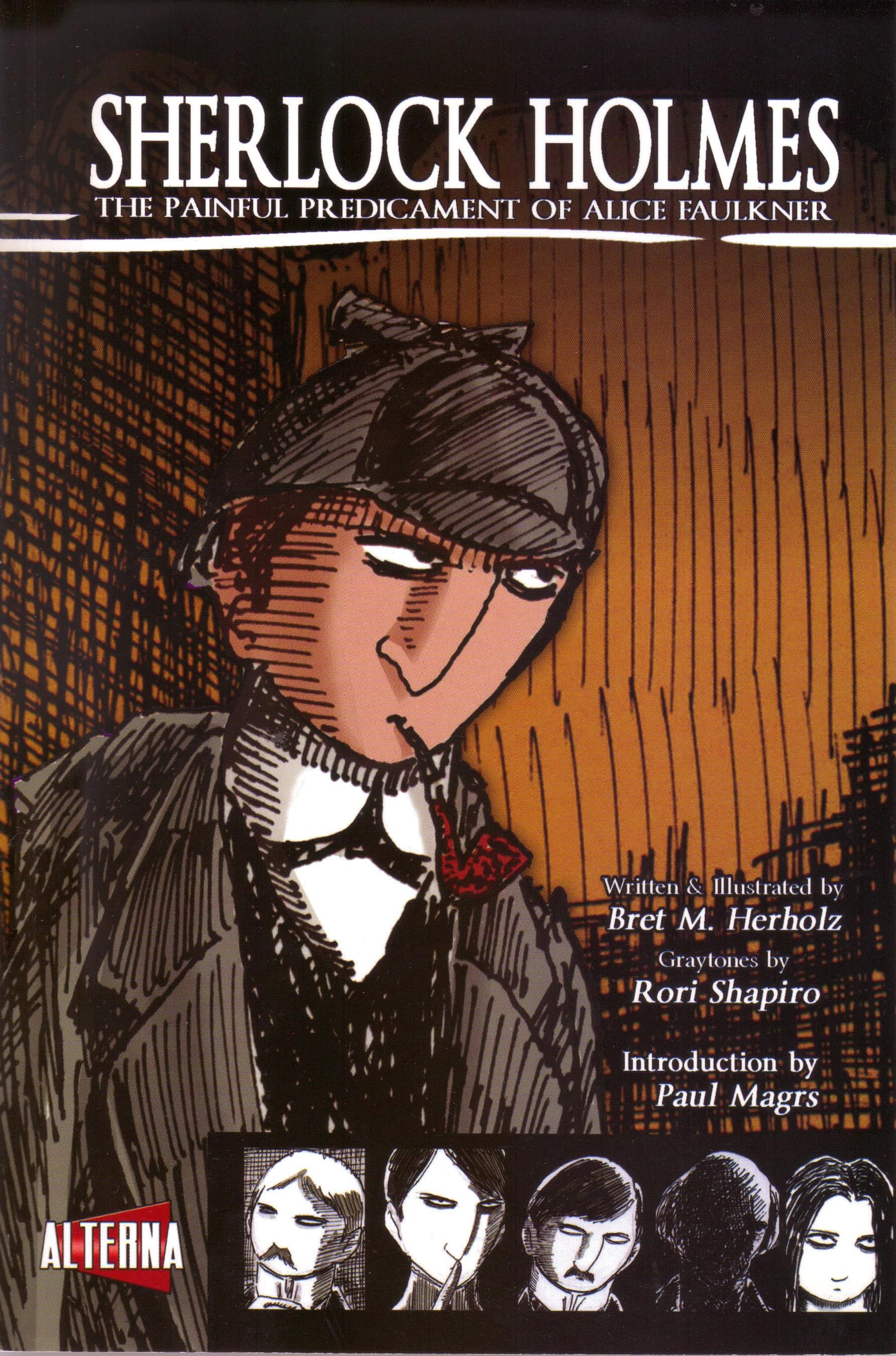

I don't really have much to say about the play, because I've never seen it, but now Bret Herholz has adapted it, Rori Shapiro has graytoned it, and Alterna Comics has published it (it's been around for a year or two; this is the third printing). It costs $11.99, in case you're wondering. And I know you are! Herholz has renamed the book Sherlock Holmes and the Painful Predicament of Alice Faulkner (the original play was simply called "Sherlock Holmes," which isn't very snazzy), because that at least explains that the victim in the case is named Alice Faulkner and that her predicament is, indeed, painful.

There are some problems with SHatPPoAF, the most glaring of which is the same problems that besets movies based on plays - this is basically people standing around and talking, with very few scene changes. The first act takes place at Edelweiss Lodge, which appears to be out in the middle of nowhere but is sufficiently close enough to London that Watson can travel there and back rather quickly. The second act takes place at 221B Baker Street. Intermittently we see an apartment in which stands the arch-villain of the piece - Professor Moriarty. But otherwise, the backgrounds of the comic are visually drab, which is a bit of a shame.

Another problem is my own personal one - Professor Moriarty just isn't that interesting. He's not in the original stories all that much, and he's referred to more as a presence, which is what he should be. When he gets directly involved, he's just not that fascinating, and it always seems odd that Holmes should have a "nemesis," as he's not a superhero nor are all of his cases all that "important" in terms of national defense or criminal greatness. The Professor Moriarty part of the latest (and very good) Holmes series (with Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman - the one that takes place in modern London) was the weakest part of the show (although it still wasn't terrible), and he's the least interesting part of this comic as well. (I enjoy Holmes when he's dealing with weird yet minor crimes, some of which aren't crimes at all. I understand why Guy Ritchie went with a giant threat to the English government in the movie, but I kind of wished Sherlock Downey Jr. had instead spent the entire movie figuring out what happened to someone's cat. That would have rocked!) He's not in this comic all that much, even though he's the arch-villain, but there's something dull about Moriarty that no one - to my satisfaction - has been able to solve. Finally, the last problem is with the lettering. Yes, I'm harping on the lettering again - back when I cracked the Internet in half by daring to review a Top Cow trade, someone (probably Ron Marz, but I can't remember) made fun of the fact that I didn't like the lettering, but that's part of the entire package, so it's fair fucking game, as far as I'm concerned. In this comic, the lettering is somewhat odd - it's quite small, to begin, but that's not too much of a pain. I assume Herholz lettered it himself, because no one is credited, and he does a remarkable job cramming long words into tight spaces ... except this leads to some odd breaks for hyphens - in one word balloon, Holmes says, "That her expression wonderful and her technique extraordinary." This is part of a longer statement, so the lack of verbs isn't too vexing, but Herholz has to fit all of that in a small space, so he hyphenates "wonder-ful," which is fine, but he then hyphenates "ext-raordinary," which throws me for a loop. He does this quite often in the book - usually his hyphens come at the right spot, but often he does what he does in the latter example, and it's jarring to read because you aren't sure what the word is supposed to be. There are some spelling mistakes scattered throughout the book, too, which is also somewhat jarring.

These minor issues with the lettering loom much larger because the book relies so much on wordplay, so it's rather frustrating.

There's a lot to like about the comic, too. The actual case is, like a lot of Holmes's cases, an odd one - it's tough to figure out if a crime is even being committed, after all. I suppose the official charge would be "kidnapping," but it's a gray area. Alice Faulkner is a young girl whose sister was involved with a high-ranking gentleman, presumably an official in the British government or a royal of some sort. A pregnancy, a broken promise of marriage, and a dead sister and child later, Alice has in her possession a great deal of evidence linking this gentleman to her sister. As she is an orphan, the villains of the piece - James Larrabee and his sister, Madge - took her under their wings and gave her a place to stay ... with the objective, of course, of making her give up the proof, which they would use to blackmail the gentleman. Sherlock Holmes is retained not to rescue Alice Faulkner, but to retrieve the evidence. Moriarty, meanwhile, doesn't appear concerned about the papers at all - he sees the entire affair as a way to trap Holmes and do him in, as the detective is becoming far too cognizant of Moriarty's maneuverings. So he sets his trap for Holmes, who of course is not fooled in the least.

I don't know how much Herholz changes from the original play, but the actual telling of the story is done well. Perhaps because of the drab backgrounds and static nature of the book, there's a sense of melancholy hanging over the entire book, giving us a very good sense of a gloomy fin-de-siècle London and the menace posed by Moriarty - as with other Holmes stories, the parts of the book in which he doesn't appear are more effective because we know he's out there, scheming, and invariably, when he shows up, it's less disturbing than when he's not present. Herholz also gives us a good portrait of Holmes - he seems a bit more complex than Conan Doyle often made him, as he seems both kinder yet calculating at the same time, less a sociopath than someone weighing all the possible options of a course. He is not retained to help Miss Faulkner, but he does so anyway, even though in the end he's manipulating her as much as he's manipulating everyone else. Apparently the play caused a bit of controversy when it first ran because Holmes and Alice have an attraction and Conan Doyle's Holmes was famous for having an aversion to women (even when that woman is Rachel McAdams), but Herholz does a nice thing by making it clear that while Holmes might be attracted to Miss Faulkner (less so than she is to him, but still), he's not above using her to clear up his case. It's a slightly more nuanced version of Holmes than the one we get in the canon, but he's still recognizable as Holmes.

How much of that is Gillette's contribution and how much is Herholz I don't know, but it's interesting. (Watson remains a nagging fishwife, but that's why he's a fun character, so it's not necessarily a bad thing.)

What also contributes to the success of the narrative is Herholz's very odd artwork. It's strange and distorted, almost as if a child who was raised in a Gothic mansion was drawing it. Herholz's anatomy is freakish, but not in a bad, early-1990s Image art kind of way - his figures are impossibly elongated, with their fingers most notably long and pointed. Everyone looks slightly alien, as if they aren't quite human, and this lends the mystery a spooky and otherworldly tone. With the gloomy backgrounds, the figure work - the most important part of the book, as it's almost all talking heads - makes the book even more disturbing. It's a style that takes some getting used to, and it's obvious that, as you read, that Herholz knows what he's doing, but it's a weird feeling looking at this comic.

On balance, the decent mystery and the creepy art help overcome the rather dull misc-en-scene and pacing, so I can say that if you're interested in Sherlock Holmes, this is a worthy book to check out. If you're not interested in Sherlock Holmes, you might not be interested, but it's kind of neat to see an artist with Herholz's style, so that might be a selling point. Herholz seems to like doing these kind of mystery/crime stories (some of them are advertised on the inside back cover), and it's a measure of my enjoyment of this that I'm probably going to check some of those out!