John Romita, Sr. is a living legend.

One of the artists who defined the Silver Age, he began his professional career while still a teenager and took over "The Amazing Spider-Man" when Steve Ditko left the book in 1966. His run on the series stands as one of the most iconic in the history of Marvel Comics. During his time on the series Romita created many of Marvel's most significant characters including Mary Jane Watson, The Kingpin, The Punisher and countless others. The longtime Art Director at Marvel is also the man responsible for one of the most iconic moments in modern American comics -- the death of Gwen Stacy, for which he remains proud.

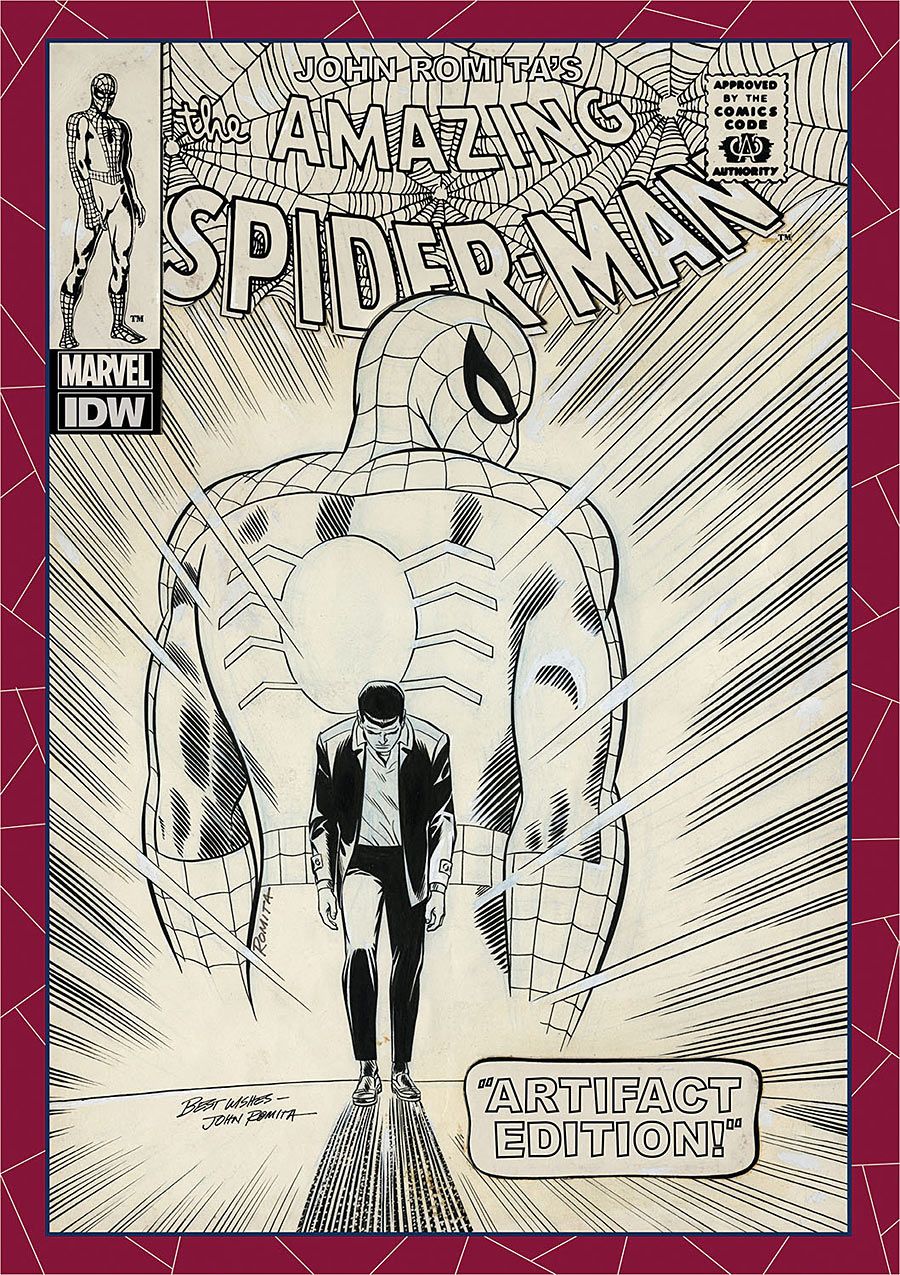

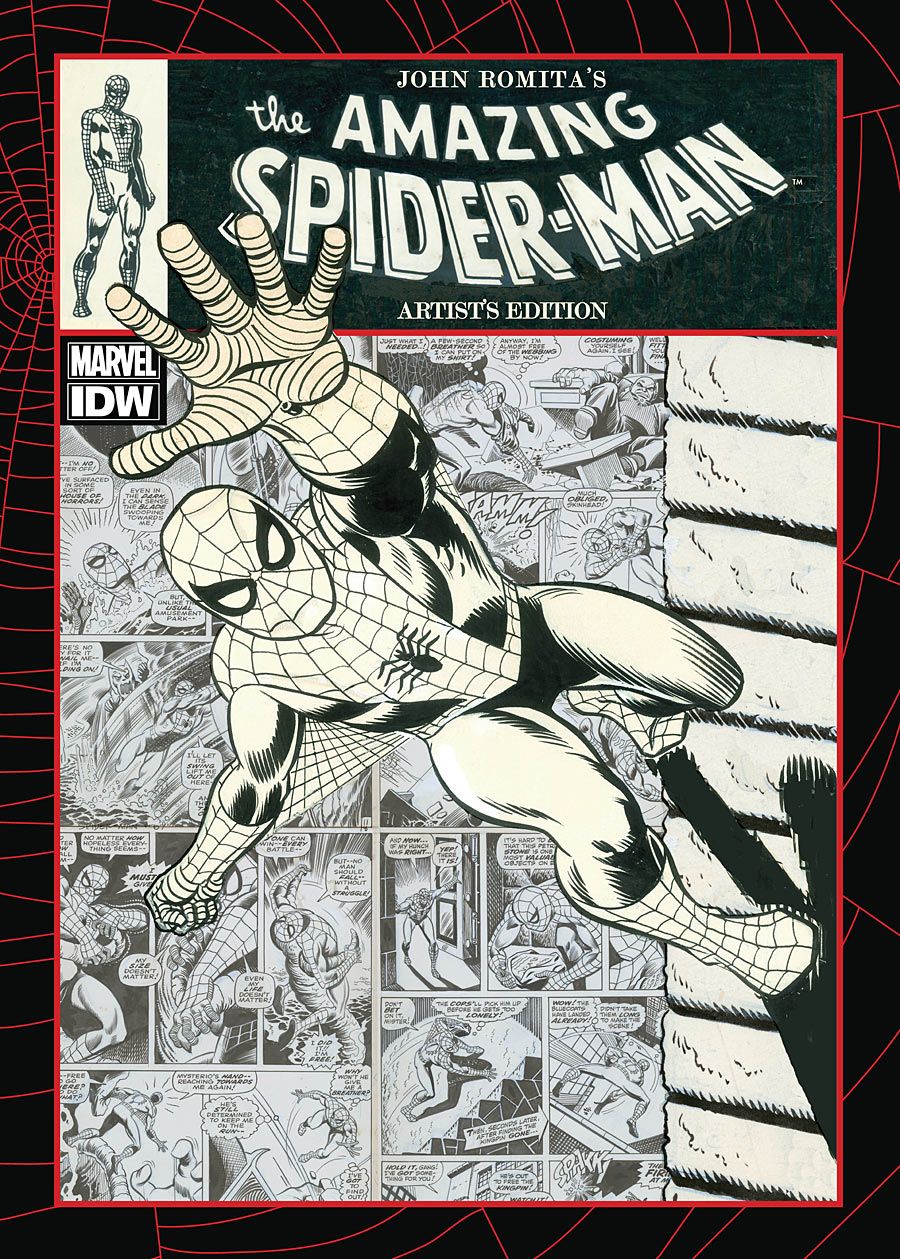

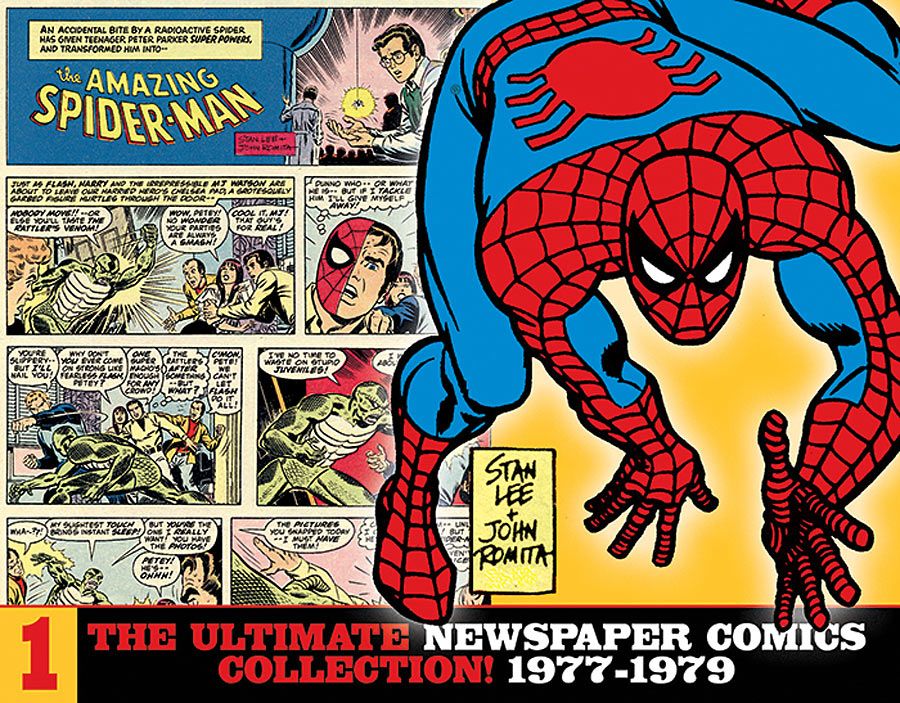

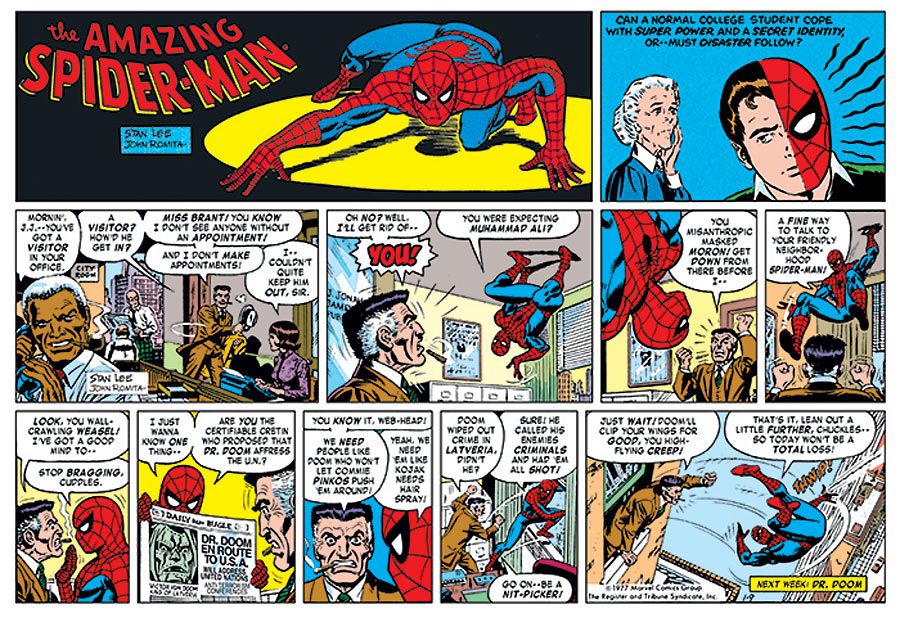

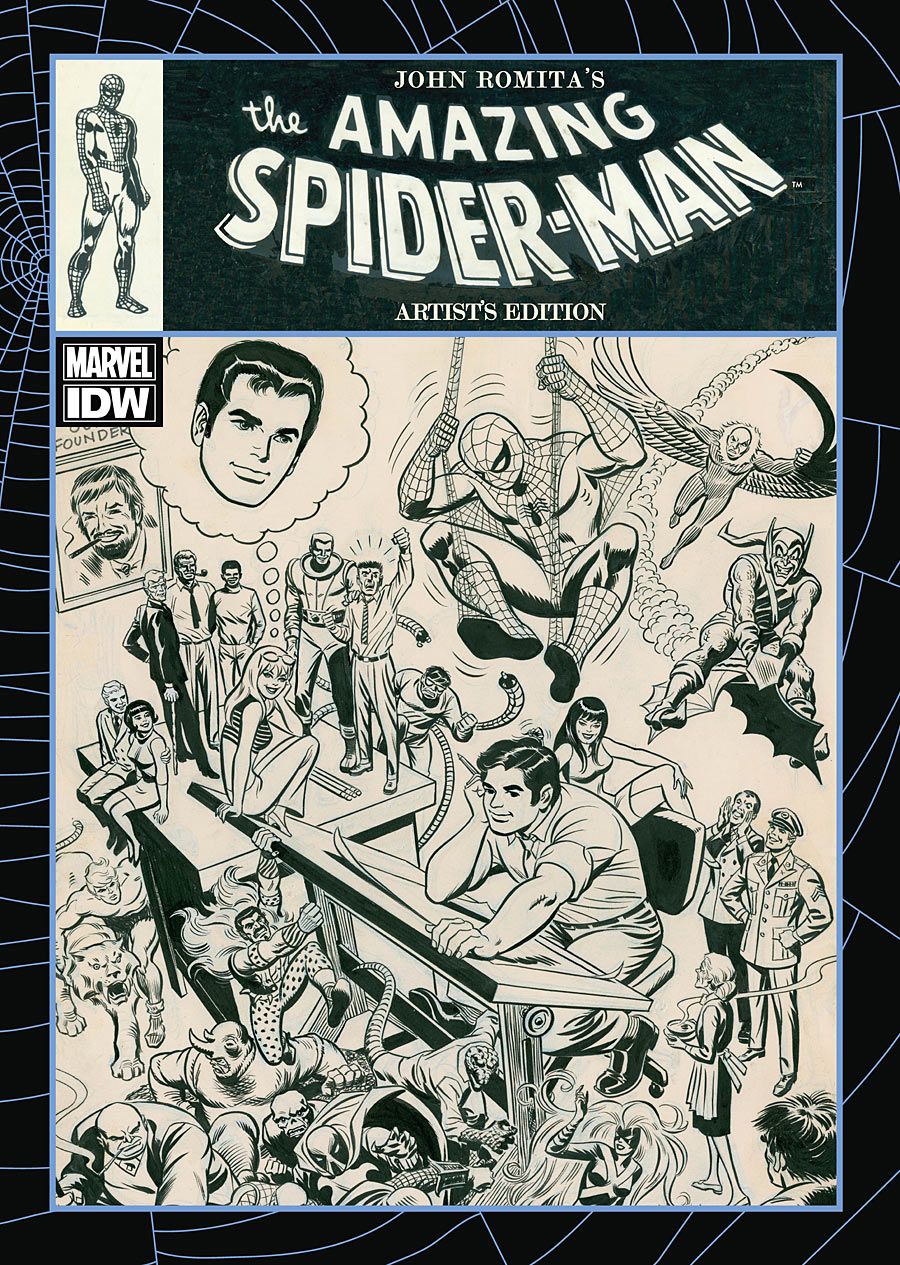

Romita's work on "Spider-Man" has been highlighted by IDW Publishing in an Artist's Edition and this year the Library of American Comics will collect the first few years of Stan Lee and John Romita's run on "The Amazing Spider-Man" syndicated comic strip. Romita recently celebrated his 85th birthday and took time out to speak with CBR News about his life and career, as well as Spider-Man's lasting legacy and the role he played in it.

CBR News: While you're primarily known for your work at Marvel, you actually started drawing comics in 1949 and drew romance comics for many years.

John Romita, Sr.: That was my penance. That's how I get into heaven. [Laughs]

[Laughs] Could you explain that?

As a guy who wanted to do adventure strips -- "Tarzan" and "Flash Gordon" and "Terry and the Pirates" -- to get into romance was like penance. It was very hard. My first assignment I got outside of ghosting was for "Famous Funnies" to do a love story. I sweated through it. I fell asleep on the board three nights in a row. I didn't know what the hell I was doing. All the girls looked like bony skeleton men. Let me tell you, the guy who hired me to do it paid me for it -- $200, which was the most money I'd ever seen at one time -- but he never printed it, it was so bad. That's how I got launched -- on a disastrous romance strip. I spent seven years at Marvel doing adventure stuff, jungle stuff and war and westerns. I was getting pretty good at it but then Marvel closed their doors and I was without work. I went to DC and did love stories. I never dreamed it was going to last eight years. It was like being in Alcatraz for eight years. [Laughs] I used to go walking through the bullpen at DC and admiring all the stuff that the adventure artists were doing. I was also secretly hoping they were going to ask me to do a Batman fill-in or something. Of course that wasn't going to happen. After eight years when they closed down the romance department I went around hoping that some of the editors might have some stuff for me to do in the adventure department, and I got nothing. Fortunately I landed at Marvel and the rest is history.

Romita's Spider-Man Swings Into an IDW Artist's Edition

When you started you wanted to do something along the lines of Milton Caniff, Noel Sickles, Hal Foster, that school.

That's what I dreamed of.

You were born in 1930, if I have that right, and there were a number of artists around the same age -- Joe Kubert, John Buscema, Alex Toth, Al Williamson.

One of the things I regretted was that I wasn't born a little earlier so I could be on the ground floor in the comics industry. I was in the second wave. Or maybe the third wave. I was destined to be a follower because the first wave -- the Kirbys, the Bill Everetts, the Joe Simons -- all those guys were in the first wave and they were breaking new ground. Nobody could tell them what was the right way to do things. They just did it the best way they could and created an industry. I missed that wave. I would have been older but at least I would have been on the ground floor.

You were in the generation after where you were reading the golden age of comics and then started working in comics at the end of that period or right afterward.

Yeah I always felt like a follower instead of a leader and creator. I was always just embellishing somebody else's creations.

I wanted to ask you about that because you've said before that you don't consider yourself a creator.

Everybody says, oh, don't give us that innocent response. It's true. I don't. The reason I lasted so long and did so well is that I could take somebody else's creations and make them better. That's good enough for me.

You see what you did on "Spider-Man" as telling stories, creating and designing new characters, but you were doing it in the world and with the characters that Stan Lee and Steve Ditko created and established.

Well, I started out ghosting it because that was the tradition. The old timers used to have ghosts doing their daily strips and comic books. Bob Kane never did any Batman to speak of. The point is that I just felt like a follower, that's all.

You were at Marvel through a lot of changes, to the point where you were working at a very different company when you left. Is there something that really stands out for you?

We had to buckle under some very severe changes. I'll never forget in '67, I think it was, when we went to the smaller original artwork page. That was dramatic for me. I was used to having plenty of room and suddenly I was working on a smaller scale. I don't think I was ever the same. I think I would have been a better artist if we stayed at the bigger size.

That was only one of the changes. Every time they changed ownership it was another trying period. They would come in and throw absolutely everything out the window and start from scratch. It was very hard to hang on after you had worked a certain way for years and then bang, you're working another way. That was not fun.

I wanted to ask about the syndicated comic strip because you and Stan Lee started it in 1977 and you were there through 1980, is that right?

I think the beginning of '81 I was off of it. Four complete years I was on it.

Was doing a comic strip a goal of yours?

Every comic book artist dreamed of being a syndicated strip artist. I used to dream about it. My problem was I had a job. I was art director and I had been doing "Captain America" and I didn't want to give up that job because, frankly, I didn't think the newspaper strip would last more than three or four years. Shows you what I know! I was very leery of starting it, even though I wanted to do it. At the time newspaper strips were dying because there were less newspapers every year. Also adventure strips were anathema. I wanted to do it but I did not want to give up my job to do it so I foolishly tried to do both. I was splitting my week, killing myself, and not getting much sleep. And I didn't make much money on it. I told Stan at the beginning, if we keep adding newspapers and getting more money out of it, I'll stay on it, but if it starts to lose money, I'm going to quit. He knew that from the beginning.

Was working in the small size of a daily comic strip a problem for you?

In the newspaper strips it was even worse. The Daily News used to have ten daily strips and those were the dream years where Alex Raymond could do beautiful brush strokes and fine line technique and you could see eyebrows and eye lashes. When I took over it was a disaster because they were reproducing stuff smaller than two inches. I ended up having to draw almost a coloring book line to keep it from disappearing altogether on the page. I wanted to stay on but they kept making the problem harder and harder for us. Stan didn't care. He didn't care if it was a half inch high -- his words were always legible. But it gave me less and less space to put my artwork.

Like drawing romance comics, you got your dream job, but it wasn't how you imagined it.

That's right. It was very difficult. It was very hard. The one thing I didn't want to do was to short cut. I had a lot of people helping me when I was late. But I never let anything out that wasn't the way I liked. The reproduction was something else. I couldn't control how bad it printed in a lot of newspapers, but I turned out the best product I could. That's why I lost a lot of sleep and a lot of money.

And you never expected that it would be still be going thirty-something years later.

It's still going strong! It's one of the biggest phenomena that people just don't seem to pay attention to. Adventure strips were dying for ten years fifteen years before I started it and this one has by all means broken the mold. I think it's sensational. I said, I'm getting off before it dies. Shows you what I knew. [Laughs]

As you mentioned, you were the Art Director at Marvel for years. How did you end up with that job and how did you approach it?

It wasn't an art director job at the beginning. When I was a kid starting out, every time I went to Marvel Stan would give me a talking to and tell me where I was doing the right thing and where I was doing the wrong thing. I got to know everything that he believed in that made Marvel Comics so explosively good. I got so well endowed with all that philosophy that I used to be able to do it with the other young artists coming in. I couldn't work at home and produce enough stuff so I asked Stan to give me a drawing board up at Marvel. Because I was there everyday, that's how I became the guy who took a lot of things off Stan's hands. I would talk to the young artists and teach them everything that Stan taught me. It was more like I was a lecturer at first. I was lecturing young artists on how to do it the Marvel way. Then eventually it turned into being the art director because I was doing cover sketches and teaching younger artists. It grew like that and I never got an extra penny out of it. I don't know what I thought I was doing but when I look back I feel like a sucker. [Laughs]

Besides Stan Lee, were there other artists and people who fulfilled that role for you?

No, there was only Stan. Stan was the guy behind it. Let me tell you, for eight years up at DC, I got very little encouragement or information on how to do a better job. There was only one editor at DC who did. She was named Phyllis Reed. She was a sweetheart. She helped me out and I helped her out. For about five years, I was doing all the cover designs for the romance department and she was plotting stories for the writers from our cover sketches. We were creating cover sketches in advance of a book and then the writers would get a plot based on the cover. She was so good.

Outside of that all the other editors at DC never gave me a moment's time. They would take the thing and give me a check and say I'll see you in two weeks. They never gave any kind of encouragement or information. They were very competitive with each other. They didn't want to teach an artist and then lose him to some other editor. When I went to Stan -- every time I was with Stan -- I learned something every day. When I would do a pencil job, if I didn't have much faith in it I would hand it in and invariably Stan would make it look like it was a well written and well planned out story. It made me tell people, "If you want to become an artist, go to work at Marvel. Stan will turn you into a storyteller."

Stan Lee gets a lot of criticism but hearing stories about that period and how other editors worked, he stands out in so many ways as a writer and editor.

He would give me a card every month with a name on it. No instructions. He would just say, next month a new character, The Kingpin. He would leave it to me. He would never second guess me. He would take whatever I designed and never criticized it. He would criticize storytelling, but he never criticized my choices. He would accept my ideas without any problem.

When I was there, everybody thought if you could draw well and you could do sensational panels, that you were going to be a success. The truth is that no matter how good or bad you are as a draftsman, if you can't tell a story, you don't last in comics. A bad story -- no matter how beautifully it's drawn -- makes no sense. Nobody is going to read it. About halfway through my stay at Marvel, I realized I was being paid to tell a story, not to a drawing. That's why my stuff is always rather simple and uncomplicated compared to a lot of guys.

I've had the opportunity to interview your son and he said that one of his big influences as a storyteller was watching old movies with you.

I always told my son, I learned more between the ages of, say, 8 and 20 from the movies about how to tell a story and how to make it satisfying to a viewer than any art school could have given me. Of course I also learned because [Milton] Caniff was a moviemaker on paper. "Terry and the Pirates" was my lighthouse. I used to spend two or three hours on a Sunday just looking over "Terry and the Pirates." First I'd read it then I'd look at the artwork and then I'd read it again. He was teaching me every step of storytelling and characterization that I used for the next fifty years.

I've read that you and Stan Lee worked a lot on different kinds of projects over the years that never went anywhere.

[Laughs] He always wanted to do another syndicated strip while we were doing "Spider-Man." I was working two jobs and he wanted to make time to do another strip. He wanted to do a humor strip. I said, "Stan, I barely make it through the week now. How the hell am I going to do another strip?" [Laughs] He said, "Oh, I'm sorry, I always forget it takes you longer to do a page than it takes me to do twenty pages." [Laughs]

We were once approached to do a replacement for "Little Annie Fanny." I tried to do one that was a little bit raunchy and a little bit sexist and all of that stuff with a lot of nudity. I did a sample for the magazine. I tried to be as raunchy as I could and it was never enough. I went to Stan and said, "You know, I'd love to have a big fancy elaborate thing like 'Annie Fanny.' It would be prestige. It would be money. But frankly I just can't be that raunchy and I don't want to put my name on something that's what I consider too raunchy." It was the only time I ever heard of Stan Lee given up something that would have been very good money. He actually said, "If you don't want to do it, I won't do it either." So we passed on it. He was happy with what I submitted. It was raunchy enough for him but it wasn't raunchy enough for the magazine. [Laughs]

I would be remiss if I didn't bring up one of the biggest events in the history of Marvel Comics, which you were involved with, the Death of Gwen Stacy.

Yes, I'm the murderer. [Laughs]

The reason I take the credit for it was we were told to kill Aunt May. Gerry Conway and I got together for our plot session -- we used to get together at his apartment -- and he said, how are we going to kill Aunt May? I said, if you kill Aunt May, you're not going to do a damn bit of good to the strip. It'll lose one of Peter Parker's hangups. He won't have to worry about Aunt May anymore. He won't be treated like a child anymore. If we want to make any kind of stir in the monthly line, we have to kill somebody important. That means we need to kill Mary Jane or Gwen Stacy.

The reason I told we should kill Gwen Stacy was Mary Jane was an airheaded comedy character at the time. She was there to jazz the place up. She was not his girlfriend. His girlfriend was Gwen Stacy. I said, I learned from Milton Caniff. Milton Caniff every three or four years killed an important character. I remember as a young boy hearing adults saying that did you see that Raven Sherman has been killed in "Terry and the Pirates?" I said to myself, oh my god, grownups are talking about "Terry and the Pirates?" They worried about Raven Sherman. Raven Sherman was Pat Ryan's girlfriend in "Terry and the Pirates." I was an avid reader of "Terry and the Pirates." It hurt me, but I didn't expect it to hurt grownups. That stayed with me. I told Gerry Conway that story and I said, if you want to kill somebody, kill somebody important or leave it alone. He said it was a good idea. He was all for it because I convinced him, that would get attention. I submit that after forty years, I think it's still getting attention. [Laughs] I think I was right.

Very definitely. But one reason is because she wasn't brought back, which isn't true of many characters who are killed off.

Stan was out of the country when we did that. He accused us of doing it behind his back and he wanted us to bring her back. Roy Thomas and I and everybody else in the company said, "We can't do that. It would be an embarrassing silliness to bring her back." We talked him into it, but he was very upset. After that, they used to kill people off routinely and it was never the same effect the second and third and fourth time.

You killed her, but she's immortal.

I take great pride in that. When people say, "Did you really want to kill Gwen Stacy?" I say, "She was one of my favorite characters." She was a Ditko character, remember. I created Mary Jane but Gwen Stacy was my favorite character and I did that knowing that that's how I could get people's attention.

Comics Legend John Romita Sr. Makes "Superman" Cover Debut

You drew a variant cover to "Superman" #34 last year, but we haven't seen much work from you in recent years. Do you not draw much anymore?

I retired in '96 and I did projects after I retired, but I did not want to do anything on a steady basis. I did a couple of short things and I've done some covers down through the years, but I've been avoiding that like the plague lately. Now I refuse to do anything. It's just too much trouble. It really is. They don't look as good as they used to look to me and I want to be proud of anything I sketch. I'm not going to go in there and do some lame sketches just to make people happy.

You can see the difference even if not everyone can.

I can. Believe me, I know when I've missed the boat. [Laughs]

Are you happy seeing the "Spider-Man" strip collected like this, from the publisher that also puts out "Terry and the Pirates," "Scorchy Smith" and "Flash Gordon," and your strip being in that company?

I am very pleased. I get very puffed up with myself. [Laughs]