Jim Woodring is arguably one of the great visionaries in modern comics. His work reads like no one else's, and like so many comics without words, it's hard to describe them in a way that does justice to the stories' complexity. When reading books like "Jim," or Woodring's recent series of graphic novels, or his collection of sketches, "Problematic," it's clear that one is experiencing the work of a unique talent, one with a particular and specific angle on the world.

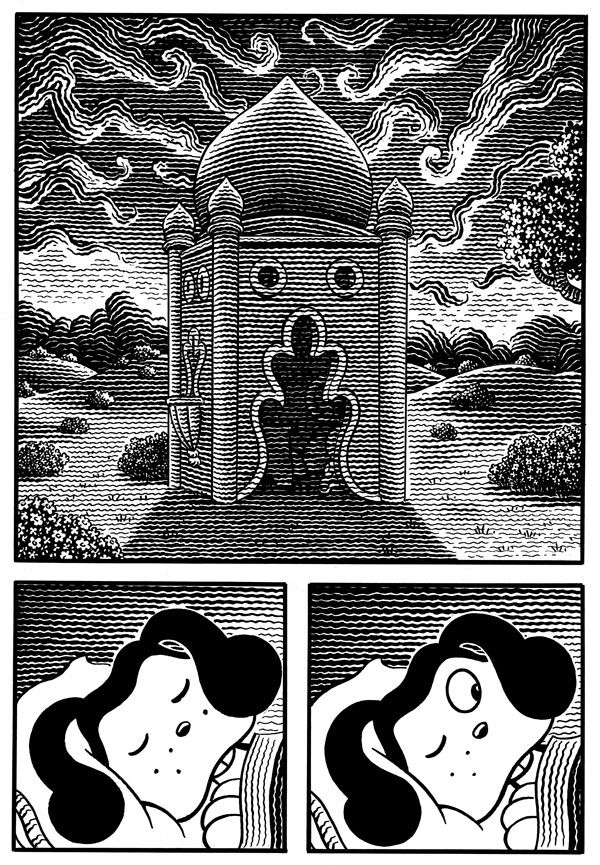

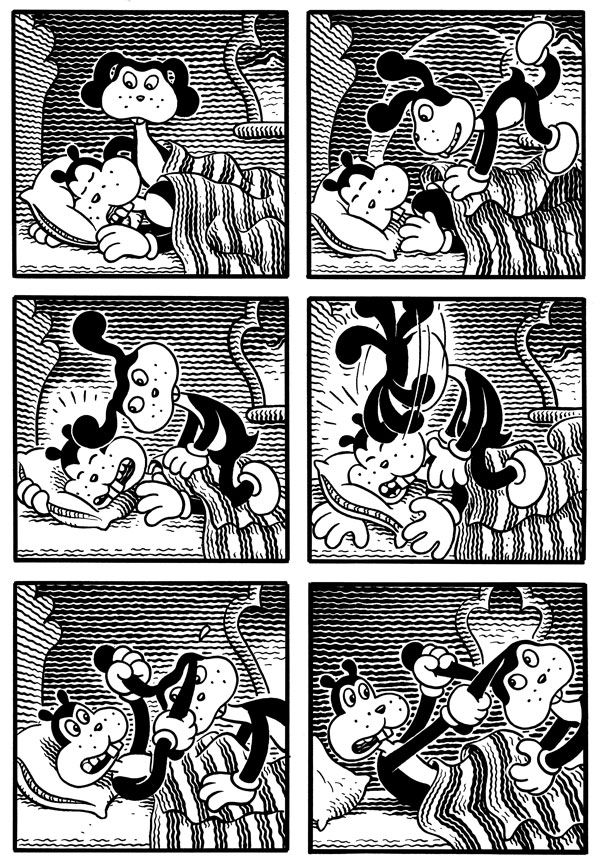

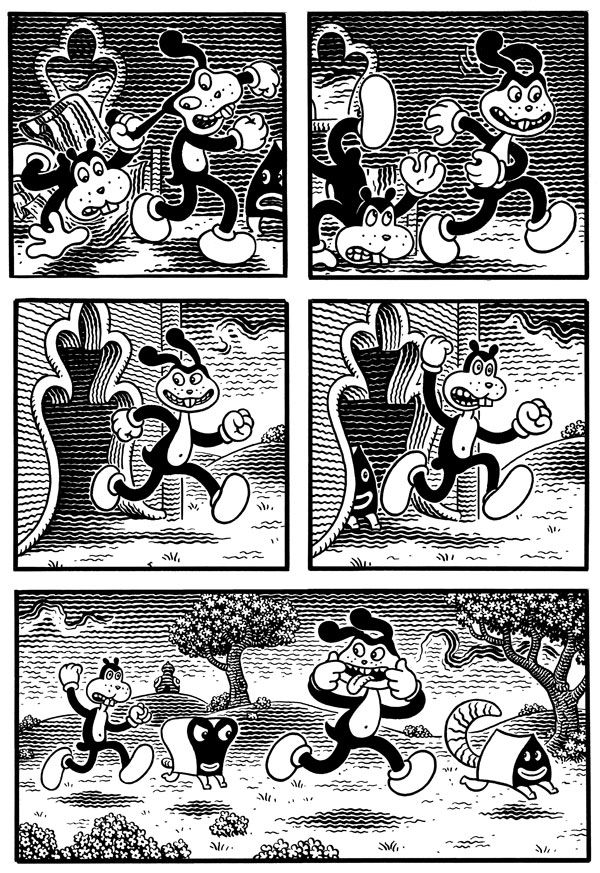

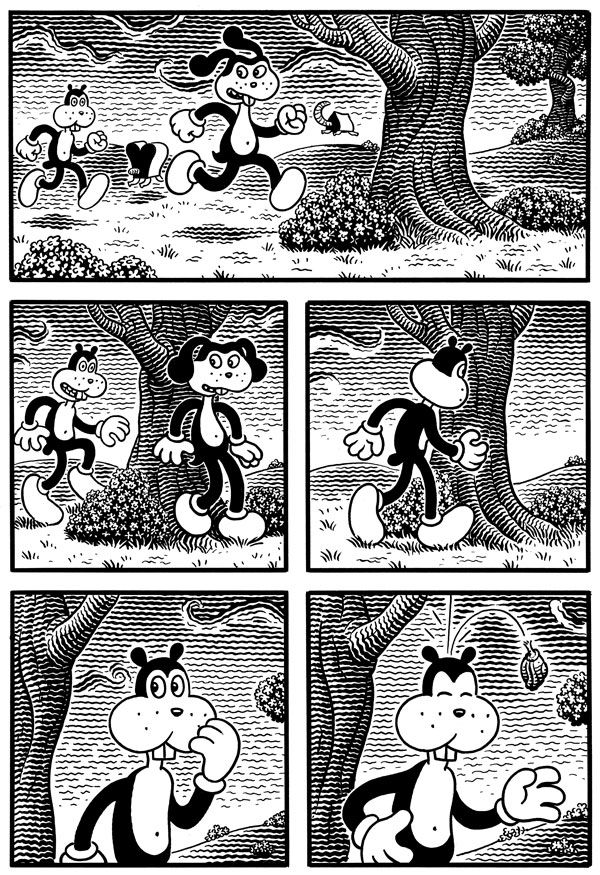

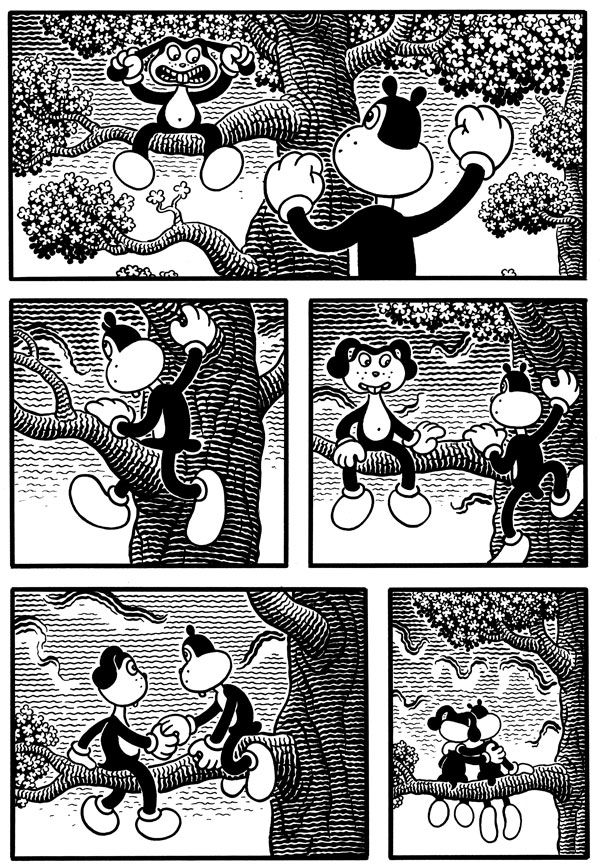

His new book "Fran" is the third graphic novel to follow the adventures -- and misadventures -- of Frank, following on "Weathercraft" and "Congress of the Animals." The Fantagraphics-published book is just as beautifully drawn as the previous volumes, continuing Woodring's tendency to be both surreal and strange, yet also very familiar and relatable over the course of the tale. The cartoonist described working on "Fran" as a particular struggle, while opening up about his next book and his work in general.

CBR News: "Fran," as the subtitle tells us is "Continuing and Preceding 'Congress of the Animals.'" My first thought on reading that was, what the heck does that mean?

Jim Woodring: Well, I guess that's what I intended you to think. It ought to spark your interest right at the door.

So, what the heck does that mean?

It means you can take those two books and read either one first and follow it with the second one; the two-part story will make sense whatever order you read the parts in.

Of all the work I've done, "Fran" is the only thing I'd call a real struggle, or at least it was by far the biggest struggle, to do. When I started drawing that story I had an entirely different production in mind -- a lighthearted frolic tentatively called "Poochytown" focusing on the characters Pupshaw and Pushpaw. The truth was that since Frank now had a domestic partner, I wasn't so interested in him. I figured his raging need to get up with the sun and explore the Unifactor would be sublimated for a while.

What I didn't realize -- this is going to sound crazy -- what I didn't realize is that the Unifactor didn't want Fran there. She was, it seems obvious when I think of it now, an alien presence in that world. More, she was a new factor in the sealed, self-justifying equation the Unifactor is always reworking. She upset the system and the Unifactor wanted her gone.

So what the Unifactor did -- this is going to sound really crazy, but I am describing a real situation -- is it invaded my mind and, over a tortuous year, made me first change and then abandon the Pups story, It was actually agonizing. The notebook I kept during 2011 is a frightening document, full of the most frantic, fruitless searching for a solution.

One strange aspect of all this was that certain motifs presented themselves forcefully -- a double spiral, for example. I used to dream of it. The idea was that midpoint was page 50 and the story would reverse itself at that point. But I couldn't figure out how to make that work, so after much wretched grappling I gave up. It wasn't 'til the story was drawn that I realized the double spiral was there. Plus I realized that "Congress" was a double spiral and that the two books compose another. So it all came together the way it wanted in spite of my ineptitude. I felt used.

Is structure important for you?

Structure is the story.

Telling a story without words, does that make the structure more important?

For me, it does. And it's a lot more work. You can't use words as shortcuts, like regular comics. I want my stories to flow along at a regular and dependable pace -- a pace that can be modulated, slowed down, for example, or just broken, for jarring effects. Besides, the Frank stories contain a lot of events for which there aren't any words.

The characters do seem to be speaking, we're just not privy to what they're saying.

You know, when "The Stranger's 2010 Genius Award in Literature" was bestowed upon "Weathercraft," beloved Seattle icon Charlie Krafft publicly denounced the judges' decision, saying, "a guy who draws mutes" didn't deserve the prize. That really hurt me, because the Frank characters are not mute. In fact, they make a lot of noise; their whole world does. Someone told me Frank uses a lot of profanity, which, according to the system, must be true.

You talked about how the book changed. Do you have a typical way of working?

When I decide that I'm going to do a story, I just put myself into a receptive frame of mind and let the ideas come. I write them down, and if they have that special fluorescent glow, they stay, and if they don't, I get rid of them. The ideas pile up and they form stories by themselves, like chains of amino acids.

These ideas feel like they are coming from outside me, but maybe I'm trying to fool myself because that is what I want -- ideas that don't seem like mine. No, I am definitely trying to kid myself, because there is so much unintended autobio in my work.

But I'm not looking for source material. I'm not trying to come up with a story like a newspaper strip artist does, who has to have a story to draw. I catch these things as they go by and put them down and look at what they're cracked up to be when they're done. They come out as stories, ready to go.

The mystery of the process is mostly what keeps me at it. Sometimes the meaning of a story is so obvious that I don't want to use it. Sometimes I can tell that there's something in there, but I have no idea what it is -- those are the ones that I enjoy working on the most. I just sense there's some meaning swirling around in the depths of the thing, and it's my privilege to bring the situation to light.

It's interesting you phrase it like that. I found myself wondering to what degree you're Frank and to what degree these books are about you in some sense.

I don't think of Frank as my alter-ego, but objectively, it seems true that he is. I never think of this when I'm actually doing the work. I think of him as "him," completely.

But, like Frank, I love getting up early in the morning and watching the new day take shape. Frank's sense of the world as an endlessly strange place, in which one is granted refuge, is something I relate to. And the extent to which, in these comics, the hammer never really falls. Frank is constantly threatened, it looks like the end is near many times, but it never happens. That reflects my view of life. We may be tortured, but we're not annihilated.

Where does the landscape come from?

The foothills of Glendale, California. The undulating lines and the shrubbery. Particularly, the hills around and behind Brand Park. If there is an earthly Unifactor, that's it.

You keep a sketchbook --

Yes. I have those little Moleskine pocket sketchbooks. I started in 2004, started filling up at least one per month. What's in them is very varied -- sketches, notes, finished drawings, popups, souvenirs, signatures. Whenever I need a monster or a scene or a gag, I can just pull out one of those books at random and I'll find something.

Do you use them to brainstorm or do work or what?

The great thing about them is there are no restrictions except to fill them. If I'm riding a bus or waiting for somebody at a restaurant or doing anything where I have a little time and I'm not distracted, I'll take out the sketchbook and put something in it. There's a collection of those drawings called "Problematic." That's a representative sample. There's about five thousand drawings that are worth looking at -- or, that I think are worth looking at.

You're not alone in thinking that.

Well, that's a nice thought.

When "Weathercraft" came out, you said that you planned to make three more "Frank" books. Is that still your plan?

Yes. "Poochytown," or whatever it will be called. It will link up to "Congress" and "Fran" but will also be completely separate. I have the opening planned out. For me, it's very audacious.

Will that be the end of Frank?

I don't know. There are so many different things I want to do. I'm focusing on drawing and painting now, because I never did learn how to paint right. I'm finding the pleasure in doing oil paintings that shock people or upset people. I have one on my easel, now. My friendly neighbor came by and he saw that picture and you could see he was quite upset by it. It's a nasty psychological thing, this picture. I like that.

I wonder how much power creepy art actually has in the world. Think of all the really famous works of art that have something really creepy about them: The Scream, The Persistence of Memory, The Song of Love, or Francis Bacon's screaming popes. A lot of the world's most famous art is upsetting. It's a great tradition.

When you started talking, my first thought was of Munch's Scream, which is this horrific portrait of depression and psychological torment that's on totebags and t-shirts. [Laughs]

It's horribly disturbing -- and it's so famous. [Laughs] I heard an article yesterday, that the Norwegian embassy presented a monster Christmas tree to some entity in Washington DC, and it was decorated with hundreds of dangling Scream baubles. Like 700 little reproductions of the scream hanging from this tree. Amazing!

Coming up with stuff that agitates and disorients your emotions and gives you a little bit of a shock and gets under your skin is such a pleasure. That's the whole point of it, for me. When I find someone whose work does that for me, I feel like I've made a friend.

Will we see you revisit the kind of work you did in "Jim?"

In a certain way, yes. In fact, the "Jim" stuff is going to be repackaged and re-released this year. Along with a lot of similar materials from the eighties and nineties, and some new stuff as well. I haven't looked at or thought about this work in years, and it gives me a bit of a jolt to be revisiting it now.

I thought I had destroyed all my old work, but oddly enough, this very day I came across a huge trove of drawings from my junior high school days on. Where this box of work came from, I have no idea. I suspect my brother may have planted it during a visit. I've spent a lot of time talking about what a screwed up kid I was, and relating all my bizarre perceptions and foibles. Some people think I was laying that on kind of thick, exaggerating the craziness. Well, I have the evidence now! [Laughs]

This early work is obviously the work of someone who was deeply and seriously out to lunch. I was embarrassed to show these things even to my wife, they're so messed up. My parents, when they saw these things, must have wept, wondering what the Hell I was. Anyway, I'll put some of these in the new "Jim" collection -- they fit.

You mentioned your auto-didacticism -- do you think that's been a help for you?

I don't think it has, but I don't think I could have done it any other way. I was on a bus last year, sitting next to a woman who mentioned that she was an authority on autism. I said I had a layman's interest in mental and perceptual disorders. We talked a little bit, and then she said, "When were you diagnosed?" And before I made my next remark -- which was, "Diagnosed for what?" -- I realized in a flash that she, an expert, had determined that I had autism and, what's more, in that same flash I realized she was right.

I recognized the truth of it, immediately. I thought, oh my God, I've been autistic for sixty years and never knew it! If when I, as a kid, some mental health practitioner had said to my parents, "Your son is autistic. He thinks strangely, he doesn't get his mind around the same things you do, he sees things you don't see, he responds to things you don't know about, it's a condition, cut him some fucking slack." My whole life would have been different. I always knew there was something wrong with me, something that made me unable to grab the old clue train, but I had never heard it identified or named before. So that was an eye-opener.

The way you talk about being self-taught, about not presented with an approach or a way to understand the world, you're making comics where people aren't presented with a way to understand them. Was that a choice you made?

In a way, yes. I wanted the stories to be easy to follow, but difficult to understand, except intuitively. I probably couldn't have learned that approach in a school -- it had to be devised out of need. Maybe if I'd learned the rudiments of making art in a school, I would have found a different way. I don't know. But there was never the possibility of me going to art school as a kid. My high school and junior high school art teachers would send me home with notes saying, "Jim shouldn't be trying to be an artist; he doesn't understand drawing or painting, he doesn't have what it takes to be an artist." Which was true, as far as it went. What I did have was this vision that I was desperate to express, and as far as I was concerned, nothing was going to stop me from expressing it. That gave me an obnoxious self-confidence. I've met people since those days who said it was interesting watching me grow up, because even though I couldn't draw at all, I never stopped drawing and it never seemed to bother me that my work wasn't any good. Well, of course it bothered me, but I was determined. I believed that I was on the right track.

Now that you've been painting, do you think that you have a better sense of color? Most of your comics work has been in black and white --

I don't think I have a better sense of color. One thing that is self-evident is that I'm a cartoonist and not a painter. If I could paint like Vermeer -- [Laughs] If I could paint like a third rate imitator of Vermeer -- I wouldn't enjoy just painting straight genre scenes, at all. It's always the subject matter that interests me and how strongly it comes across. Even though I just paint in primaries and secondaries, and I don't have a lot of sophistication, those tools are enough for me to get my ideas across. That's all I want to do. If people say, "You're no painter," I say, no, I'm a cartoonist.

You're still just trying to chase the best way to express this idea you have in your head.

Yes. It's just a matter of getting the idea across somehow. New methods are being invented every day.