In a year filled with Batman-centric blockbusters and crossover events, some fans may have missed Scott Snyder's experimental, half prose, half sequential A.D. After Death, which he and collaborator Jeff Lemire released through Image over the last year.

RELATED: Scott Snyder Says Dark Nights: Metal is Rebirth’s ‘Strange Twin’

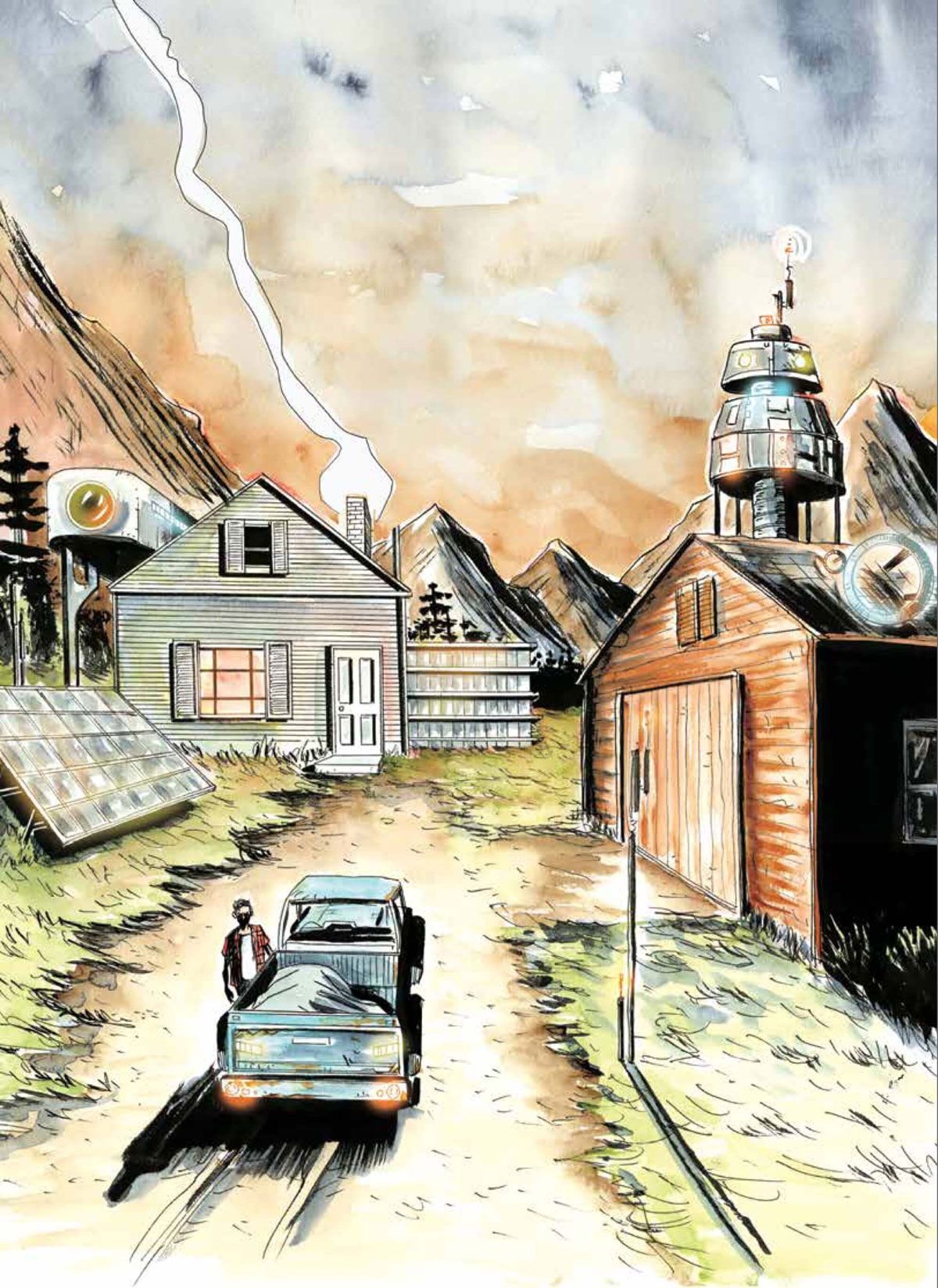

With that in mind, CBR caught up with the fan-favorite writer to discuss his and Lemire's rather personal project. A.D. is hitting shelves again, this time in collected hardcover edition which gathers the three oversized issues into one trippy, sci-fi-flavored beat poem about life, death, time, and a shoplifter turned art thief turned kidnapper caught in the middle.

CBR: To start out, let's get a little bit of background on the story of A.D. as a whole. How do you feel coming off of this project?

Scott Snyder: A.D. really took a lot out of me. It was really tough. But I’m probably prouder of it than I am of everything I’ve ever done. It has a whole history for me. I started writing in prose but my last experience with prose was rough. I had a great time writing this story collection but then I was working on a novel, and the isolation of it was really rough. We moved out to a more rural area -- the area we live in now -- and it the isolation of writing, doing all basically in a cave, dealing with the pressures of needing the book to be something that was commercial for Random House -- all of that stuff, just really made it nerve wrecking. I had a ton of anxiety over it. It was a rough couple of years.

So, when comics came along and gave me the opportunity to work in something I’d always wanted to do, it pulled me away from prose entirely. [Laughs] I was like, “I never need to go back there!” So, when I started working on AD it was really scary. Jeff was the one who encouraged me to go back and do prose for it. But, to be able to have finished it and made something that was really close to something I’d always wanted to work on, something that meant a lot to me, it gave me a ton of confidence. Coming off of it, I feel like I can try a bunch of stuff now I probably would have been a little nervous about before.

In revisiting A.D. in a collected format, it became really obvious that the narrative in the story is very deliberate in its nonlinear formatting. How challenging was it to sit down with Jeff and articulate the way you both wanted this story to unfold? Where did the pacing of the issues really come from?

RELATED: EXCL: All Star Batman To End, But Snyder Promises Stories Will Continue

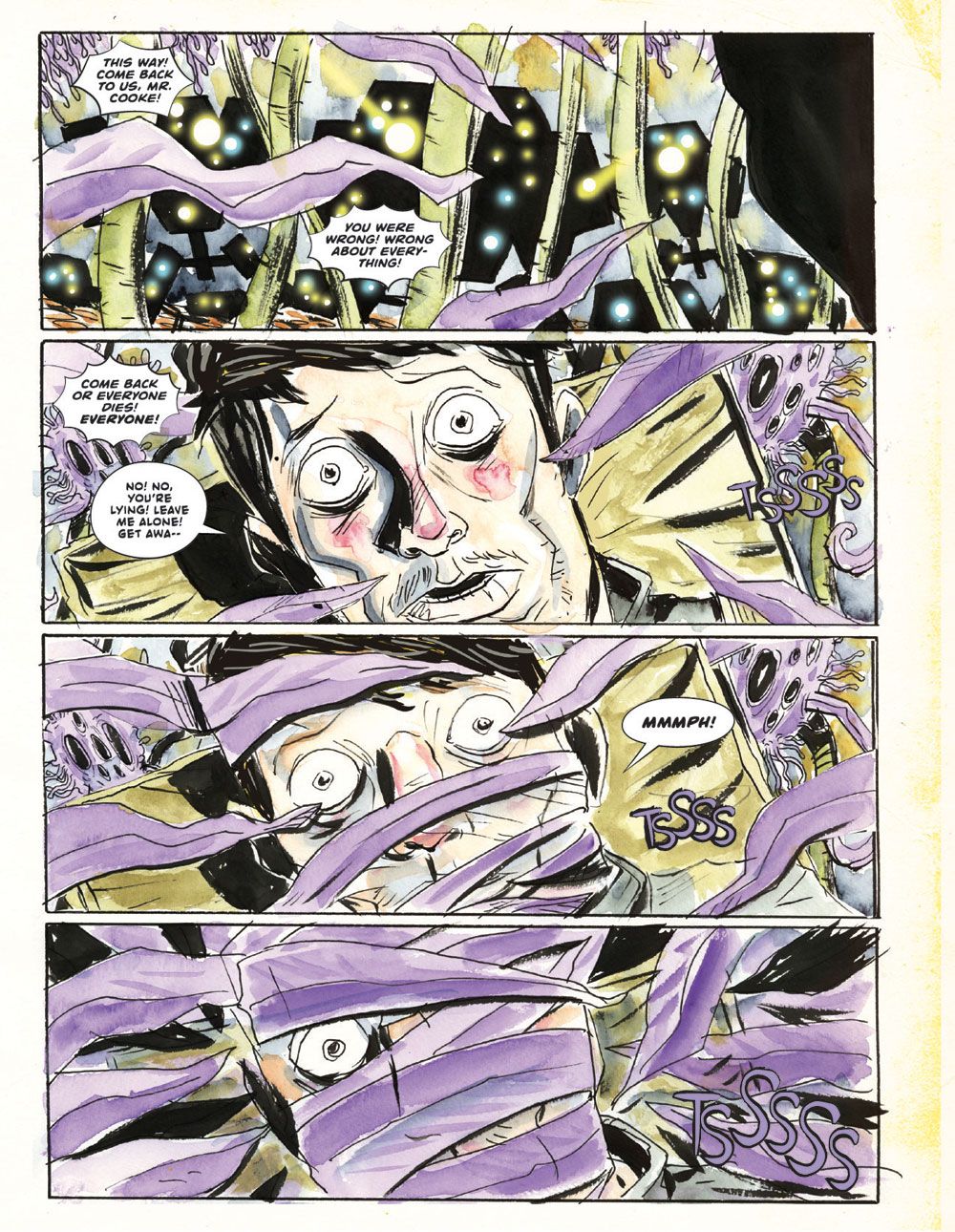

It was really interesting! Jeff and I are really close, so we talked a lot about it. We wanted to do something that was unconventional for both of us in terms of what we’d done so far structurally as storytellers, but also something that would allow us to dig deal into the things we enjoy doing the most. Jeff was very encouraging with setting up the sort of design that would allow to take as much room as I needed to really tell the story through all of this personal material I was working with, and then we would balance it with this speculative, bombastic sci-fi. In that way, setting up the architecture of the story was actually part of the fun.

I was nervous about it from day one. I kept worrying it was too slow, or too myopic -- but I think the balance of it just sort of became the priority. Obviously, telling the story emotionally was a component but also we started thinking of it as an architectural piece. We had to think about balancing the prose with the art, we had to think about telling the story in a way where it folded back on itself but doesn’t reveal too much. It was a very different map than I’ve worked with before. But it gave me a lot of enthusiasm for trying new kinds of storytelling in the future as well.

I think that sort of scaffolding within the story really worked, it’s something that becomes really apparent when you read it in collected format all in one go.

Oh, thank you, I really appreciate that. It was important for us to construct something that would give room to tell a story that was a sort of [autobiographical] needle point in a sense that had something big and sci-fi on the other end of it. It was a balancing act with Jeff. It was on him to provide the stunning visuals for the world building, and then I would get to go into that as close, emotionally, as I could. It was a really great marriage in that regard and it was a great process to work through with him.

One of the most interesting parts of AD is the fact it’s this very personal, emotional story built onto this very hard sci fi spine with things like genetics, medicine, and even the deep web woven into the world. How much of that was researched or based in reality and how much of that was fantasy concocted by Jeff and yourself?

It was pretty researched! My wife is a doctor, and I always feel like she’s the science brain in the house. So I’ll always end up calling her about things like “If Bruce Wayne is hit by a gamma ray…” and then I’ll just here a *click* and the line will go dead. [Laughs] But one thing she’s become great at is actually directing me towards people I can talk to or helping me find scientific articles that speak to some of the things I’m fascinated by when it comes to story cues. She’s been great about that.

So, a ton of AD is really researched. The ______ stuff, all the stuff on theft, that was a lot of fun to research.

RELATED: Batman: Snyder Updates Duke Thomas’ Superhero Name, Series Status

I always love fiction where you can’t quite tell where it’s going off the rails. I try to do that with both Batman and American Vampire. You end up in crazy town after a little bit but when you’re describing like an invention that Batman has or a the physiology or a different kind of vampire, you make it sound as if they’re a real thing. I love it when it hits just over the line where you end up thinking “that’s not real is it?” [Laughs] Those stories are always my favorites. I try to go for them whenever I can.

[Laughs] I think you definitely got there with this one. You really could have answered that question either way and I would have thought, “oh yeah, of course! That makes sense.”

Good!

But now that we’re looking a little deeper into the content of the story itself, I’d like to talk a little bit about Jonah himself. He’s a very atypical sci-fi hero, if you could even really call him a “sci-fi hero.” He’s got a very blue collar, almost incidental persona about him. Where did the inspiration for him as a protagonist come from?

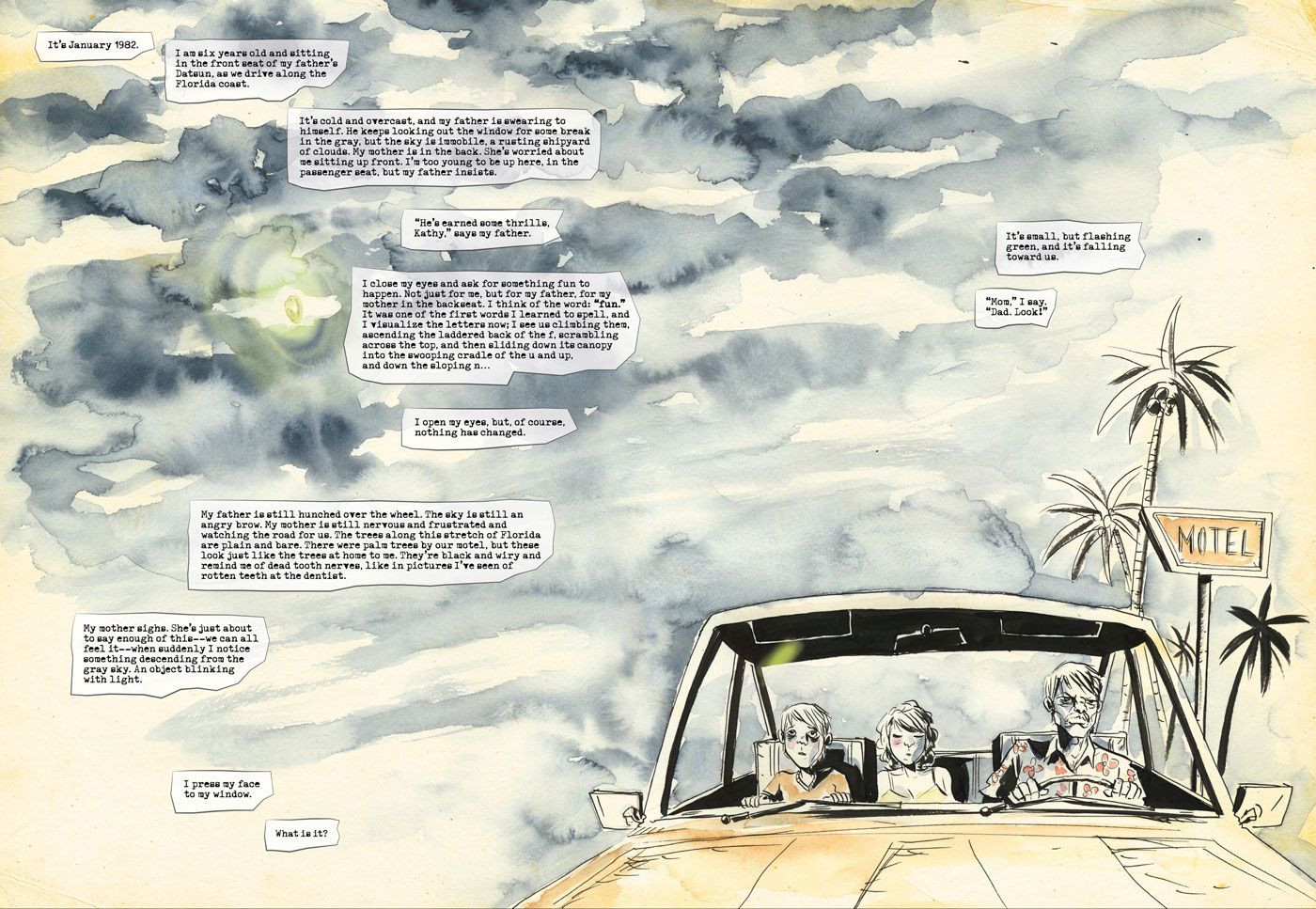

The idea of being him being a thief was one of the components of him that was there from the beginning. I was talking to Jeff at the start about how when I was a kid, I had a lot of anxiety and I had this habit of stealing things. Mostly harmless things, but still. I never really understood it, but it was this obsession with that and also with the concept of recording things -- you know, family events and stuff -- that are really personal to me. It’s the sense of removing things from the systems in which existed before, it was fascinating to me. So Jeff was like, “we should expand on that! We should make him a character who does that, and that is an extension of him.”

[We wanted to focus on] this sort of “core flaw” and really have him be the one responsible for both the start of Retreat, and also the one responsible as a person who really typifies the possible end of everything.

He’s a lightning rod, emotionally, for all the built this place, but also all the things that would take it apart -- the skepticism, the wonder of it, it comes down to somebody who finds himself [in the Retreat] for reasons that are relatable and also completely damning.

Writing him was strange because -- coming from a place of having kids and being married, being a dad grounds me so much more anything else at this point. So there are these vast differences between me and Jonah, yet he and the father in Wytches, Charlie, are the ones that are the closest that are autobiographical in different ways. There’s always a strange feeling writing them in that regard.

That makes sense; you don’t want them to be too close, but you want them to be honest.

Yeah! Because here’s the thing: there are these embarrassing things about yourself, or there are things that you feel self conscious about, like, “Why am I focusing on this when there’s such important things going on? Why can’t I stop thinking about these things? What’s mis-wired in my head?” In Wytches, it was like, “Why can’t I be happy as a father immediately? Why aren’t I reacting to it the way I’m supposed to?” All of those things that you typically, in life, don’t want to talk about, in writing, there’s something really cathartic about putting them out there. Yeah, it might be a “selfish” story, it might be a myopic story, but hopefully it’s not. Hopefully other people have similar experiences. There’s something very uncomfortable writing those characters, but you know you’re doing it right when it feels unsettling in that way.

RELATED: Scott Snyder Reveals Dark Nights: Metal Details and the Dark Multiverse

A lot of the recurring motifs in A.D. have a very mythological feel to them, between the immortality, and the mountain top retreat, and even the elements of theft and trafficking. There’s this subtle “Greek Tragedy” sort of feel to the whole thing -- was that an intentional consideration, or is that me reading way too far in?

No, no, there was a section initially, actually, at one point, where Aaron actually describes it that way. He calls the Retreat a sort of Mount Olympus. The idea was that the people who live up there in that pantheon were often flawed in worse ways than the people below them, and the hope is that they’ll learn to be better. He explains that that is what people are up [in The Retreat] to do. It’s one of the oldest stories of mankind, the idea that we’re not supposed to look up to these ethereal, celestial beings, we’re supposed to become them, and in becoming them, we learn to be better. It just became too much, you know? [Laughs] It was too much to put in.

But there were a lot of fun research to it. I read a few books like The Book of Immortality, which was buy a guy who worked for The New Yorker, and explored all these different ways in which people seek out different forms of immorality, from things like cryogenics, to the more spiritual side of things. A lot of the researched centered on folklore and mythology -- he would trade not just the desire for immortality, but the stories that we wind up telling about it back to things like Greek myths, and really look into how those stories materialize in different ways over time. There’s real power in those stories.

Jeff has this way of writing that I really envy. When he’s writing, he’ll kind of block everything else out -- he’s very free form. His first drafts are rough, but they’re always primal in their emotions. He’ll just write with abandon, he’ll just put the stuff he cares about down. I have the opposite process, where I really need to know that it’s mapped out before I go in. With A.D., Jeff would tell me to think of it more like a poem, something more dreamlike, images you take from stories and myths, just let them circulate.

It was a really interesting process in that way, too, because I had to write differently just because of the dichotomy between Jeff and I.

I can’t speak enough to Jeff’s generosity and how inspiring it was to work with Jeff was a friend and as a creative partner.

To kind of tie it all together as we wrap things up, I think it’s pretty safe to say that A.D. has an ending that’s both bittersweet and incredibly open. There are a lot of ways the story could be read or understood after those last couple pages. What do you most hope readers will take away from the story as a whole?

For me, my initial draft, actually had him taking a step into the water [Laughs] But Jeff and I just thought it somehow betrayed the spirit of the story to have it end up like that. We didn’t want it dark where he ends up going back, either, but we wanted it to be something that you had to decide for yourself.

I know this sounds kind of hokey, but... in thinking about the sort of things that overwhelm you, the grandeur or the anxiety of it all, no matter who you end up talking about it with -- a therapist or a friend or what have you -- it’s something that you ultimately end up dealing with alone. To me, that’s the biggest thing you can overcome in your life -- how do you relate to the fact that you have this one time, this amount of hours and days, whether you take it as a call to action, or you retreat from it, whatever you do.

So, at the end of the book, I find himself in a good place with it. But I didn’t want to make it too easy. So, for us, for me, he does take that step. But what I really hope readers will take from it is that -- honestly? If any of these things are something you struggle with at all, not just that we’re all gonna die, but these more acute anxieties, that maybe, at the end of the story, you don't feel so alone with it.