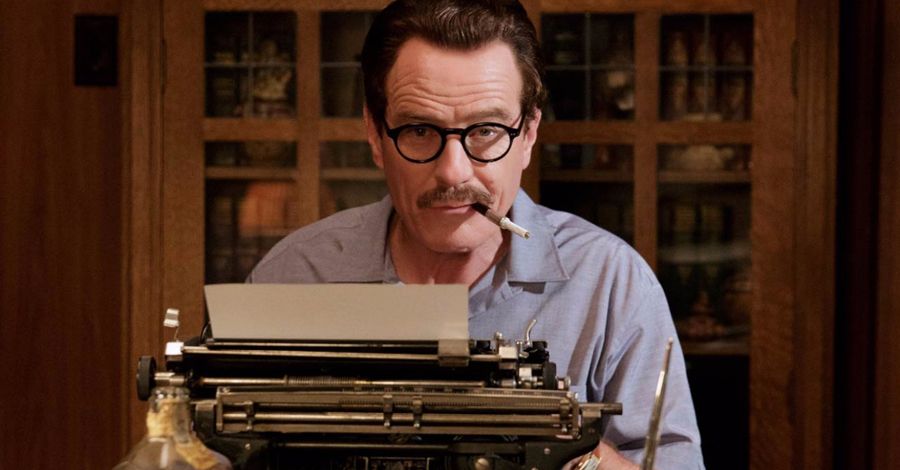

The era of Hollywood blacklisting, when writers, directors, actors and other show business professionals were denied work because of their suspected political beliefs and associations, was a dark time for both the industry and the country. But now "Trumbo," a film starring Bryan Cranston, dramatizes the struggle of one clever, determined screenwriter and shines a little light on the period.

Prior to the blacklist, the colorful, larger-than-life scribe Dalton Trumbo was a Hollywood golden boy: An accomplished fiction writer in magazines and award-winning novelist, he rose through studio system to pen hit films of the 1940s, including "Kitty Foyle" and "Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo," becoming both an Oscar nominee and the highest-paid writer in Hollywood. Trumbo was also a pacifist and anti-war activist, with strong ties to the socialist values of the Communist Party in the era before its ethos was co-opted by totalitarian Soviet politics.

Subsequently, Trumbo's own politics and loyalties came to the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee, which sought to question high-profile left-wing activists in an attempt to gather information about their intentions, often leaving lives shattered with its strong-arm smear tactics. As a result, scores of Hollywood players who refused to cooperate found themselves on the blacklist, barred from working in the industry again.

But Trumbo quietly fought back, both to ensure his family's survival and to make a point. He cranked out scripts for both the big studios and the lowest-budget productions in town, either using fellow writers as fronts or working under pseudonyms. Sometimes mini-masterpieces first intended as schlock films would result, like the gangster classic "Gun Crazy" and the noir gem "The Prowler"; other times Trumbo's fronts and false aliases would be nominated for the Academy Awards: His original screenplays for both "The Brave One" and "Roman Holiday" took home Oscars, even if Trumbo didn't.

In "Trumbo," the screenwriter's long battle back from the brink of creative oblivion is brought vividly to life, thanks to a screenplay by first-time screenwriter John McNamara and the assured direction of filmmaker Jay Roach ("Recount," "Game Change") and a bravura, chameleon-like performance by Cranston ("Breaking Bad") in the title role, bolstered by a deep bench of supporting players that includes Helen Mirren as Red-baiting gossip columnist Hedda Hopper, Diane Lane as Trumbo's wife Cleo, Elle Fanning as Trumbo's daughter Nikola, Michael Stuhlbarg as left-leaning actor Edward G. Robinson, and Louis C.K. as a character billed as an amalgamation of several of Trumbo's fellow blacklisted writers.

Several of the key players as well as members of the Trumbo family gave Spinoff Online an oral tour of their experience bringing the screenwriter's story to the screen.

Bryan Cranston: I’ve been an actor for 36, 37 years and this is my industry, this is our industry, and this was a blemish on our industry. But it was also a blemish on our country, when a branch of a government can overstep their power and under the threat of imprisonment force you to answer questions that were long fought wins in civil liberties – the right to free speech, the right to freedom of religion, to assemble. The government has no right to ask any of these questions. Whether or not he was a member of the Communist Party is none of their business. To compel them to answer or send them to prison is wrong in any advanced, enlightened society.

Jay Roach (director): It wasn’t that long ago when actors and writers and directors and producers and studio heads were turning on each other and actually trying to destroy each other’s careers and ruin their lives. It was a remarkable time. It was only a few decades ago. I guess I’m always fascinated by how politicians, or messengers let’s say, can exploit fear of a real threat to kind of go after political enemies who aren’t really a threat. The whole big lie of this was that somehow American screenwriters were going to convince Americans to turn Communist through mainstream American movies that were all approved by studio heads, and somehow corrupt America. That was like a spell that was cast based on fear. I’ve always been fascinated by how bad ideas get spread.

John McNamara (screenwriter): I actually knew four blacklisted writers in New York City when I lived there … It’s still, to me, almost unbelievable that it happened in America. Here, right where we’re standing. It happened in Hollywood. It’s almost like science fiction to me. That’s why I love the story. It’s unbelievable, but true.

Diane Lane: There are still people who are around who endured it and who are alive and are of a certain age, and I know people whose parents were blacklisted. And they carry this sort of … it's like Kryptonite in your pocket or something. It's weird, this aversion to thinking about it or talking about it. The more you talk about it, the bigger it gets … I knew Dalton Trumbo's name, but I didn't realize that he had written and not gotten credit for his writing on two of his films. And I didn't realize that he wrote "Roman Holiday" – I did know he wrote "The Brave One," but I didn't know the story behind it. So it takes a while to rectify history because we have to have people who are passionate enough to do it. And when you see the healing of the wounds that come from rectifying history and telling the story of the victims and not just the way history is portrayed by time marching forward. The version of America that the media wants to present to itself, like a conveyer belt, it just feeds itself. So we need to bump up against it occasionally and get it off course to remind ourselves that we have to really look at what we've done, so we don't repeat it.

Elle Fanning: I didn’t know that the blacklist happened. I didn’t know about the blacklist before I read this script. So I was very shocked that that happened in Hollywood. I couldn’t believe, because I feel like our community is very accepting of other people’s opinions. That’s what we are, you know? Every movie is a different point of view, so to me, I couldn’t believe that someone would stifle that, stifling their right to speak out, so that was just so interesting. Also, of course there’s like old Hollywood glamour. There’s nothing like it. So we definitely, yeah, there’s no recreating that. But we can in movies, and I think it’s fun to watch a movie that is set in that time.

Mitzi Trumbo (daughter of Dalton Trumbo): I think the fact that we, as children, had to keep a lot of secrets. And we were told everything. Our parents were very open, everything they did, everything our father wrote. So even when I was five years old, I knew the names of all his movies. But we couldn’t tell anybody. So that’s kind of weird. It did make us very close because we could talk to each other and we shared this experience. To me, our parents did it as well as anybody could.

Nikola Trumbo (daughter of Dalton Trumbo): The most difficult part was working as hard as we could to make sure it was done right the way that we hoped it would be done, I think was the hardest part. Not hard in the sense that we were dealing with uncooperative people, but hard because of the responsibility we felt to our father and our family that this work out well.

Fanning: Getting to play Niki Trumbo was really special. And I hope that I did her justice in that way, getting to talk to her before filming, we got to email. She was so open and willing to answer anything, and she would send me back these paragraphs to the answers to my questions. Specifically to the relationship that she had with her dad and how it was definitely a very unique one, specifically because of what was going on in the time in their life. So I was so happy to play her and such a strong girl. It was exciting to play.

Mitzi Trumbo: He was never bitter. He wasn’t bitter, he was determined. Yes, he had a great sense of humor about it. Not about the blacklist itself, because he took very seriously the fact that so many careers of his friends and everyone in the business, how much they were affected. And he took that very seriously. That made him angry.

Cranston: I really had to listen to the voice of Trumbo, and there is a lot of source material and video tapes and audio tapes on that. But you can kind of get lost in that. And if you only focus on that, you could start down the road of impersonation. And so I wanted to be very careful not to do that. That being said, he was a very flamboyant character, contradiction and irascibility and passion. I mean, he was a beautiful, wonderful, big character – and direct. But so it's kind of an amalgam of research to read the books about him, talk to the people who knew him …

Roach: Bryan’s a passionate person in real life, but he’s also a passionate, committed person in the characters he chooses. Trumbo and Cranston have a little bit in common. He thinks hard, he works hard, and he performs the ideas he cares about, the things that matter to him. He’s very passionate and articulate, and funny, too – serious and funny at the same time. So to have that kind of overlap with these larger-than-life characters is kind of a director’s dream.

Cranston: The challenge of working in a bathtub is not to get pruny fingers! And not to drink too much before you get into the bath tub. It becomes very pragmatic when you think about it [Laughs]. And also, after a while, staying in there for an hour or two or three or whatever it was, and then kind of sheepishly asking, "Can I have another bucket of hot water?" Because the bathtubs we used, they weren't part of those bathrooms. We brought those tubs in. So we just plugged up the drain, and they had to fill it with, hopefully, hot, soapy water. And then you discreetly placed that typewriter so that no one sees something they shouldn't. Believe me, no one should see this.

Roach: [When you're dramatizing a true story] there’s something that the audience senses that’s authentic about the story you’re telling. There’s something real that they recognize, some of from their own lives, some aspect of things that are really going on. I do like transporting them, in the case of some of these period dramas too, a place using archival footage, using actors playing real life people. Where you can explore ideas removed from yourself, but almost without realizing it completely related to what you’re going through in your own life.

Michael Stuhlbarg: I imagine there’s a lot that’s in common [with Hollywood then and now] in terms of people’s desire. People are still star-struck by the movies. They still get taken in. It’s just that there are many different mediums in which you can see entertainment these days. So that’s a big difference. It seems as though interesting work is happening on television, online, everywhere; on stage. And at that time, there was a great sense of glamour about the movies. Maybe nowadays, it’s a little more sordid. At least, perhaps the sordidness is out in the open a bit more.

McNamara: The part of [Hollywood] that’s great and terrible: It’s all about money. Trumbo understood that if you make movies that make money, no one cares about your politics, in the end. He proved that. And it’s still true.

Cranston: It's definitely a cautionary tale. But the film, first and foremost, is entertainment, and I think through entertainment, we will have more people possibly taking with them the message that is behind it. I think any time that a government sets out to oppress civil liberties that the citizens need to be very concerned about that and speak up and stand up for their rights. And so that is the cautionary tale. Now, hopefully, this generation, the younger generation, will be able to learn by that and remember that and see its parallels when they pop up.

Roach: It is not uncommon lately for congressional committees to be formed based on fear and outrage. Suddenly, a panel is interrogating someone and calling them un-American and socialist and spending millions of dollars and end up not exactly rooting out any new truths. That happens once in a while, even in the modern world. I don’t think it’s a partisan issue, I think it’s just a symptom of a kind of win-at-all-cost disease that our political system suffers from.

Lane: Dalton Trumbo really did a tremendous service to this country when he undermined them at their own game with a stroke of genius. And this movie needed to get made. And it's just a perfect story that happens to be true. And the fact that John McNamara did such a tremendous job bringing it as a screenplay because he encapsulated so much information into one family story and one man's journey.

Nikola Trumbo: Hopefully, he'll be remembered beyond the history of film as an American hero, as a real patriot, as a believer in the First Amendment, as all of those things. I think that that may well happen with this film.

Cranston: You know, it’s people like Dalton Trumbo and the rest of the Hollywood Ten and many, many, many more who paved the way and sacrificed for those of us, all of us, benefiting from a healthy show business environment, and hopefully an honest one -- and one without collusion and one that embraces all people and all ideas. And we’re pretty good at it. We lead the world in many ways socially and I think we can continue to do that: telling stories that other people might be afraid to tell.

McNamara: It’s the rarest true story there is. It has a happy ending. Most true stories don't have happy endings. This one does.

”Trumbo” is now playing in select cities ahead of wide release on Thanksgiving.