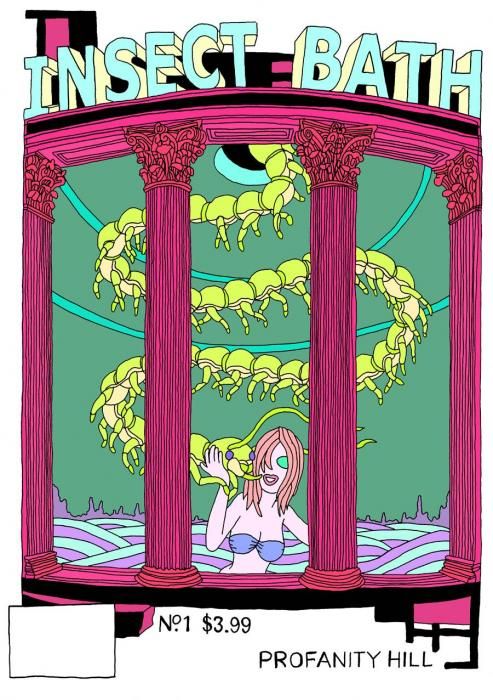

The very name "Insect Bath" as a comic book title evokes both the odd and eye-catching names of the many weirdly-titled underground comix of the 1970s, and also conjures up a pretty horrific experience if thought of in literal terms. That is exactly the intent of "Insect Bath" #1 edited by Jason T. Miles, who also contributes one of the eight stories in this wildly eclectic assortment of creepy, disgusting and disturbing tales, which for better or worse does indeed evoke the spirit of those old undergrounds, both the good and the bad.

Zach Hazard Vaupen's "The Hair Cut Back" is strangely reminiscent of both, and at the same time. Vaupen's dark, murky style requires some pretty intense scrutiny on the part of the reader to figure out just what's going on, and at times is practically indecipherable, starting with the very title of the story as early as the second panel. It's not an ideal leadoff story as it sends an ill portent for the remainder of the book, which fortunately is largely far more readable. The story, though, has a surreal, Kafkaesque feel that's so odd it's hard not to finish, and has a kind of absurdist hair-is-people-too message that provides a compelling reason not to settle for a bad haircut.

"Nightmare" by Sammy Harkham, conversely, is far more readable and is practically the yin to the previous story's yang. Harkham uses zip-a-tone to effectively produce grey midtones, and his art combines a Mike Allred style of simplicity with Chris Ware's almost draftsman-like backgrounds. It's a laid back look that eerily belies the nature of the story, whose protagonist concurrently suffers nightmares on multiple levels; her life is an emotional one, punctuated by a figurative one at the story's end, after waking from a literal one at its start.

Another strong effort is Matthew Thurber's "Race Does Not Exist," which is a pretty comical look at the absurdity of racism that extrapolates beyond the worst-case scenario when people of different races make contact. Thurber makes a simple and effective commentary on racism by throwing in the horror aspect, and adds a little more humor with some well-placed cliches that heighten the irrationality.

Amongst the other stories, Max Clotfelter's "I Eat Mold For A Living" is a tour through all things disgusting, as a boozing slacker walks out on his family and goes on a binge that leads to a weeks-long mind trip, and eventually a grossly intense comeuppance that reads like a back-room, double-dog-dare collaboration between Peter Bagge and R. Crumb. Miles' untitled entry is a revealing narrative behind the genesis of this comic and is illustrated with exquisitely detailed lines and textures. And the final story, "All God's Creatures" by Alex Delaney, is a cautionary tale warning that self-gratification combined with a disregard for life can lead to far worse things than going blind.

The meanings of the comic's two remaining stories are elusive; Juliack's ugly "Throw Her Against The Walls" is mercifully only two pages long, and Eamon Espey's untitled effort is a puzzling but oddly attractive piece that's notable for Espey's use of various manually-rendered, detailed textures and its trippy, mysterious journey from a dirty alley outward to the cosmos.

As a whole, "Insect Bath" #1 succeeds on two levels; the good outweighs the bad and there is enough worthwhile content to justify its purchase, at least for those who "get" underground comix and are willing to expect the unexpected. It also succeeds in paying homage to all of those old undergrounds, both the good and the bad, warts and all, but does so boldly and with its own voice. It's counter-culture's own box of chocolates; some are great and some are wretched, and the fun is discovering which is which.