Zack Overkill is in it deep. His old employer, the Black Death, wants him dead for turning state against him. His old adversaries, the S.O.S. have captured him, rendered him once again powerless, and want to use him as bait to catch whoever the Black Death sends after him. And his only friend from his cover life is dead. Yeah, he's in it deep.

Ed Brubaker has a knack for putting characters in seemingly intolerable situations, penned in by enemies all around, and lacking any hope of getting out of it alive. And, what's more, the characters all do it to themselves. Zack is in this situation, because of the choices he made; he chose to turn on the Black Death, and he chose to go against the terms of his witness protection agreement and begin using his powers again. He's a hard guy to feel sympathy for, especially since Brubaker has written him to date as a whiny, crude guy.

But, there's something still compelling about Zack Overkill. Yes, everything is all his fault, and, yes, he's a whiny scumbag, but... you just can't help but root for him. Brubaker and Phillips build up the world around him here with the actions of the supposed good and bad guys differing little, almost suggesting that there's no other way for Zack to act. In a world where the good guys apparently cut up the brains of their enemies, often leaving them to rot in padded cells, is it any wonder that Zack is such a bad guy? His captors at the S.O.S. seem to take glee in abusing him, ruing that they can't do more since they need him alive.

It also helps that Brubaker throws in the odd moment of pitch black comedy. A stoned Zack being asked to say some words at the memorial service for Farmer, and only managing to croak out, "...His first name was Phileas...?"

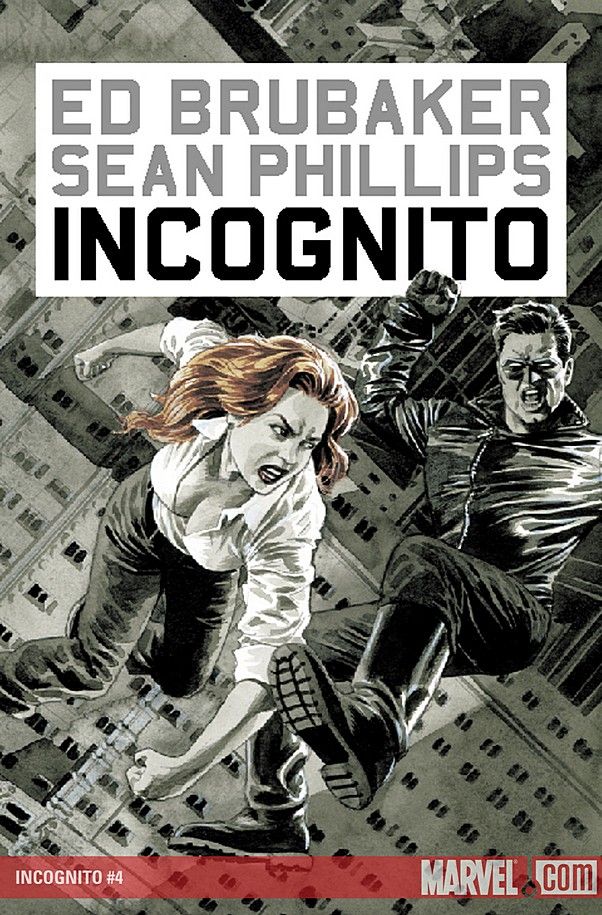

The real star here, though, is Sean Phillips. He is one of the best artist working in comics right now. Words can't sum up how good his art is. Throughout this issue, he uses a three-tiered layout, but constantly shifts it and plays with panel sizes, giving each its own sense of weight and meaning. He only allows panels to hit the edge of the page in certain instances for emphasis, often opting for gutters around every part of the panel. The choice to have no panels touch, as well, is interesting, forcing you to look at each as independent from the others.

Beyond that, his character work is superb. The man can draw the hell out of faces, conveying so much emotion with each expression. I don't know what else to say about it, honestly. It's too good for words.

"Incognito" is a compelling story with some of the best art you're going to see this month. Brubaker and Phillips, as always, work in perfect harmony.