It's 2013, and headlines reading "Comics aren't just for kids anymore" have been cliched for about 25 years. Art Spiegelman's Maus is a classic, Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis is widely read and widely taught. The late Harvey Pekar's name is, if not a household name, as close to one as those of most prose authors get in America. Thanks to Joe Sacco and Alison Bechdel and Jeffrey Brown and John Porcellino and Joe Matt and Chester Brown and dozens of other cartoonists, journalism, autobiography and memoir are successful, respected, even commonplace genres for the graphic novel, which, it's worth highlighting, is a term that exists now.

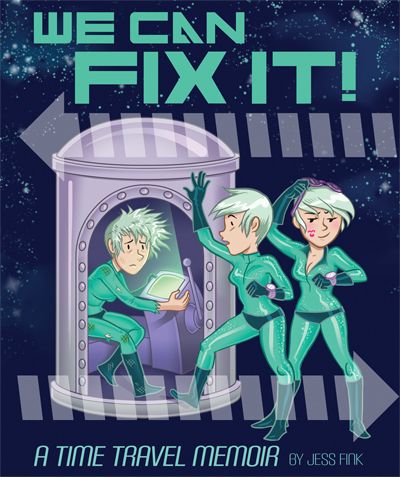

In fact, autobiographical graphic novels are so mainstream that Jess Fink's We Can Fix It reads like an outlier — a subversive, transgressive reversion to the good old bad days of comics. Her new memoir, with its fictive premise, is differentiated from most in the genre by the prominent inclusion of elements from the medium's trashy superhero and humor past. Its protagonist wears a skin-tight bodysuit, she travels through time in a big, goofy time machine that goes ZIPPITY ZAP, and there's a sixth-grade lunch period's worth of scatalogical humor.

Despite the embrace of the low-brow aspects of comics history — We Can Fix It looks and reads like an autobiographical comic book, not an autobiographical graphic novel — Fink's new work ultimately ends up in the same thoughtful, dramatic, epiphany-having place that the slicker, more obviously literature-focused comics works do. This is a very funny comic book that is functions as an effective piss-take on the autobio genre while, remarkably enough, simultaneously being one hell of an autobiography.

Fink's book, billed by publisher Top Shelf as a "time-travel memoir," features the Jess Fink of the future using a time machine to travel back into her own past to relive some of her fondest — and sexiest — memories by watching them occur before her.

After trying to enjoy acting as a voyeur to some of her own sexual history and, naturally enough, making out with herself, Jess soon realizes that once the rose-colored glasses of nostalgia are removed, some of her memories aren't quite as sexy or happy as she remembered them, and she sets out trying to teach herself to perform better (a strategy that culminates in a "masturbation" session that is basically an orgy with a half-dozen version so herself).

This may come as a surprise given Fink's previous best-known work, the well-regarded robot erotica Chester 5000, but Fink, working in a looser, more stripped-down, big-head style, doesn't try to present such scenes as hot; despite the early focus on sex and our hero's expressed interest in her own sexy past, the scenes are played for laughs.

This, for example, is as hot as the girl-on-past-version-of-the-same-girl sex gets:

Beyond her own sexual gratification, Jess is just trying to help out her own past selves, but eventually she realizes she was kind of a brat at times, and, in an effort to make herself a better person, goes a little nuts appearing in her own time-stream and generally making a pest of herself.

In an increasingly hectic adventure, she gradually comes to some realizations about the past, present and future and what makes us who we are. She also appears on the school bus to poop on the head of boy who was bullying her as a kid.

Fink the creator doesn't screw around with what Fink the character's screwing around with time travel might actually do to the integrity of the time stream or the universe or her own memories or life — speculative physics and paradoxical logic problems aren't the reason the real Fink's making a comic with a time machine in it, after all. Rather, it's a device through which she can re-present formative memories from throughout her youth — some happy, some sad, some traumatic, most dramatic — in a fast, funny way that doesn't require too great an amount of detail or attention.

It's a like a greatest hits of the memories that might appear in a memoir were Fink engaged in a more straightforward, traditional memoir. It's also a meditation on nostalgia and regret, and both the limitless appeal and severe limitations of wishing you could change the past. And it's got a lot of jokes about boobs and poop.