Having introduced the comics-reading public to such obscure or long-forgotten creators as Herbert Crowley, Fletcher Hanks and Walter Quermann in his seminal book Art Out of Time, editor and publisher Dan Nadel opted to try something a little different for his sequel, the recently published Art in Time.

While the new book, like its predecessor, does feature a number of barely-known or long-forgotten golden age and underground cartoonists (Sam Glanzman, John Thompson), it also offers a new look at some familiar and in some cases already well regarded figures, in the hopes of either giving scholars and fans a chance to reconsider their artistic abilities (as in the case of Mort Meskin and Pat Boyette) or re-examine their work in a new light via previously unregarded material (John Stanley, Archie artist Harry Lucey, Wonder Woman artist H.G. Peter)

I had the opportunity to talk with Nadel over email about the book and its rather specific goals recently. Though he was in the midst of celebrating all things Jack Kirbyish at the Fumetto Festival in Lucerne, Switzerland, he was kind enough to take the time to offer some thoughtful, considered responses to my flailing questions, for which I am ever grateful.

How did Art in Time develop and did it change at all in conception as you worked on it?

The first idea was actually to take well known artists like Kirby, Ditko, Everett, et al and show their lesser known work. This became a little less interesting as the reprint boom took hold. By less interesting I mean not necessary. I tend to think of books as being necessary or not necessary. And then, when necessary, as being well done and useful, or badly done and destructive. Anyhow, as an outgrowth of my publishing activities, and as a kind of strategy of moving away from any perceptions about Art Out of Time, I began to look at adventure comics a lot, particularly crime stuff like Pete Morisi and Harry Lucey. And then I thought of the underground stuff I like and realized (again -- maybe I'd forgotten? I don't know.) that what drives my "scholarly" (or whatever) interests was pretty much the same as what drives my publishing interest, i.e. in my head CF and Bill Everett are pretty much on the same playing field. So I latched onto the broad idea of "genre" comics and then went a little micro and focused on an idea of "adventure" that can include gumshoes and psychonauts and utopians. Then I really dug in and had some fun.

Did you first have the notion to do a sequel to Art Out of Time right upon finishing that book or did it come later on after much persuading?

Well, I started thinking about it about 6 months after AOOT came out. I hadn't initially intended to do one, really, but somehow in 2006 it seemed like a cool idea. One motivation was that I hadn't been able to include Jesse Marsh or Harry Lucey in AOOT and I wanted to do something about both artists. So no one was twisting my arm or anything, but AOOT seemed to be on its way to doing well enough to justify a sequal of sorts.

Can you talk a little about the differences between the two book and what made you try a different tack this time around?

Both books were guided by my own interests. I'm selfish that way. The big difference is that in 2004, when I began work on Art Out of Time, the stuff I was interested in (Boody Rogers, Fletcher Hanks and other recent "giants") were nowhere to be found. They seemed to be written out of history. So AOOT was a recovery mission in part. And secondarily, as with the new one, I was looking for a way to understand and contextualize the work I was publishing and enjoying. It seemed (and still does seem) to me that comics history was very conservative, and that the many byways and blind alleys and etc. that existed had been kind of smudged out or something -- I was looking to demonstrate that there were ton of different approaches possible and that the supposed "weirdness" of, say, Paper Rodeo, had precedents (though sometimes unknown to the artists themselves) in comics history.

So I did that, I guess. And then AIT is more about casting a smaller net to look for specific examples of artists who successfully navigated genres and came through with individual visions. Given that most of the comics I publish can broadly fall under the "adventure" category, you can see why I'd be intrigued. Plus, since AOOT came out in 2006 comics history has changed radically as my generation and my slightly older contemporaries basically define and invent our own artistic past. From Chris Ware's brilliant work on Frank King to Frank Santoro's championing of Thriller. Obviously these are different works qualitatively (yes, smart ass, I think King is in another league) but the basic "act" is the same: An artist laying claim to an ignored part of comics and saying "see: this is where I come from. This is my history." This is crucial. I didn't feel like I needed to be quite as hardcore with Art in Time. I wanted to show some precedents, I wanted to bring certain artists (Marsh, Lucey, Boyette, Rudahl, Glanzman, for example) intro focus, and once again advocate for looking harder and longer at artists we've passed over and for looking hard at the connections between mainstream and underground comics. The commonalities of purpose.

While you were putting the book together, were there any last minute "discoveries" that you felt you had to include? How aware were you of these particular artists before you started the book and did you learn anything new while putting AiT together?

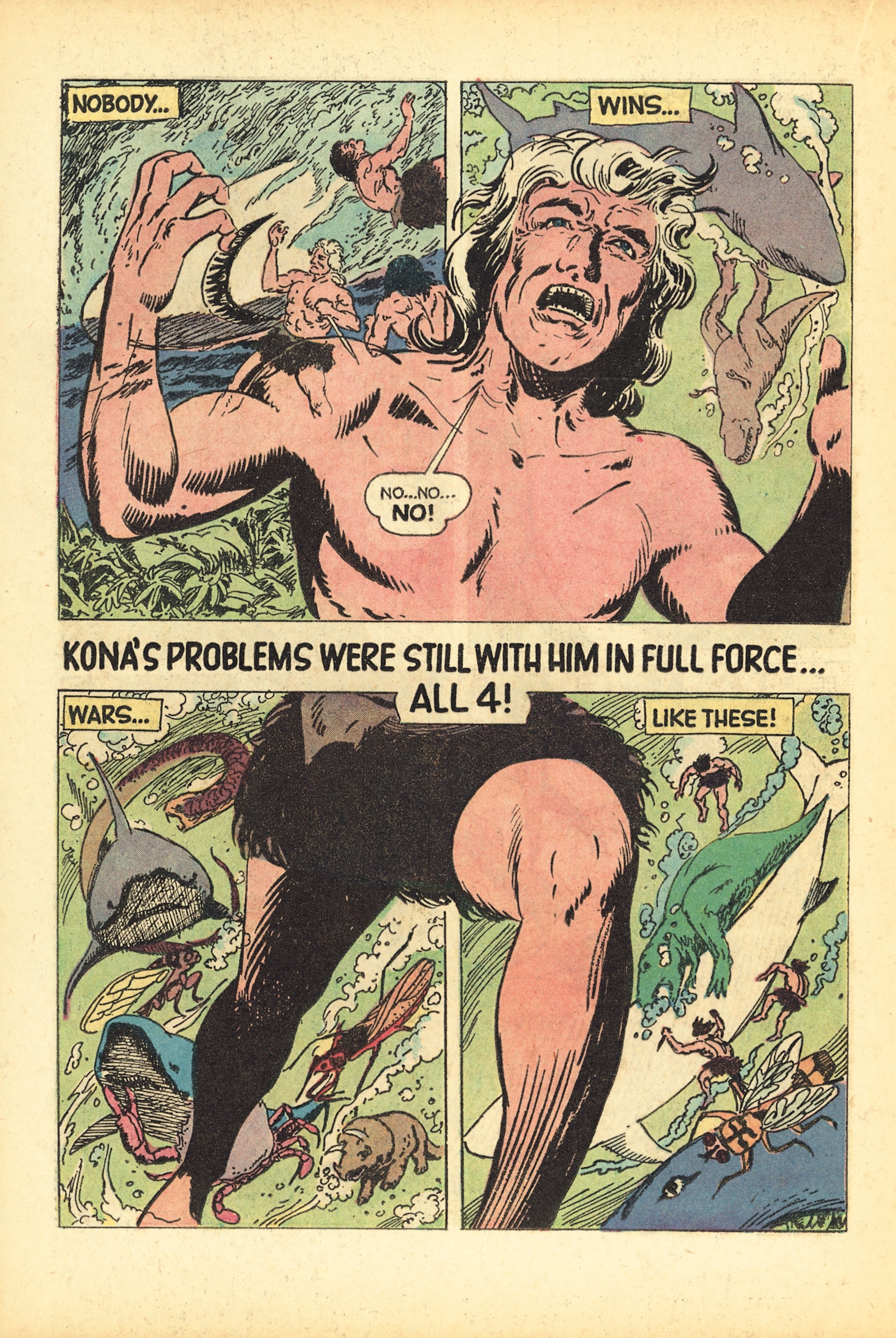

There was nothing super last minute, no. There were latecomers, like Sam Glanzman, but not last minute crams. When I started the book I was aware of about 75% of the artists. The ones I wasn't, like Glanzman, Peter, Rudahl, and Fox, were suggestions by trusted peers. I learned a bunch new-ish things while putting AIT together. I learned that I have an endless appetite for comic book drama: for the emotional hysteria of Glanzman's Kona, for example. I learned that Bill Everett is a far better, far more interesting artist than I ever knew, both personally and professionally. In terms of elegant, visceral drawings in the traditional of Alex Raymond, he's unequaled. And I would take him over Raymond any day. His drawings comprised a unique world, even when drawing "naturally". I learned that, as far as I can tell, it's mostly only other artists can understand how an artist like McMillan might flow naturally from Everett, or how Thompson is related to H.G. Peter.

Can you talk a little bit about the research involved in finding these old stories and, in some cases, locating the still alive creators and their families? I would imagine, for example, that it took a bit of work to locate John Thompson or Willy Mendes.

Best case scenario: Finding the stories was a matter of deciding on the artists, the cross checking what had been written about them, then gathering samples from various places, then checking those against various interviews, etc., to find what either the artist or his peers considered his finest work. Then choosing my favorite from that pool. Worst case: Deciding on the artist: Gathering everything they did. Then making my own choice from that pool. I worked in both modes. Of the still-living artists I suppose Mendes and Thompson were in fact the trickiest. Rudahl, McMillan, and Glanzman were, I think, in the phone book. Thompson I found via some old correspondence he'd had with a collector friend of mine and Mendes through a variety of different google searches. Persistence, basically.

You cover a wide swath of time in the book and include a lot of visually different authors with different artistic styles and goals. What, do you think, connects them together, apart from what you said earlier about "adventure" stories.

I would think that the common goal of all is to tell the story that's in their head. Different sub-goals spring from there like: get paid; buy groceries; get laid; exorcise a demon; etc. I'm going to be kind of a dick about this and say: Why do we even have to ask what connects them? They're arists; they worked in genres with defined boundaries; they each had a unique voice that pierced those boundaries. And, frankly, they all have me in common. I'm not out in front like an asshole, and I'm not about "owning" it, but let's be honest: It's me. I am confident and maniacal enough about my sensibility that I am willing to demonstrate it and thrust it on people, backed up by good writing and good art direction. That's what it is.

Along those same lines, what is it specifically about the "adventure" genre (at least as it's represented here) that you find so fascinating, as opposed to the humor or superhero comics of the same period?

Superhero comics are very interesting and the best were done by Kirby, Ditko, Colan, Everett and others for mainstream companies. That stuff has been well covered elsewhere. I would love to put together a book on that stuff, but publishing realities are what they are. That said, to me adventure seemed to have less baggage, offered artists a little more freedom in the sense that they could be auteurs a bit more easily, as there was perhaps less riding on it? Superhero comics are bound by certain rules as well (uh, except when Kirby was involved) while the others are a bit more free to go to psychologically and physically more complex places.

The release of Art Out of Time preceded a slew of reprint projects, many of them based off of artists that appeared in that book and the book was seen by many online pundits as being one of the more influential books about comics in recent years. Do you agree with that assessment or do you think you were just on the crest of an already forming wave (if you don't mind my making a horrible analogy)? Were you surprised by the book's reception and the critical success it endured?

I tentatively and humbly agree with that assessment. For the record: Paul Karasik was hard at work on his Fletcher Hanks book at exactly the same time as I was working on AOOT. But, and this is a big "but", I would never take credit or assert ownership over the stuff. I think more than anything AOOT simply made it clear that (a) there was a lot of open territory out there (b) there was an appetite for the exploration (i.e. purchase) of said territory and (c) the "canon", such as it was, was kinda irrelevant. But sure, I was/am surprised by the amount of books that have come after it. I had no idea that people were interested.

As a historian I'm thrilled when they're done well (see any of Jeet Heer's books and the announcement of an upcoming Greg Sadowski/John Benson team up) and disappointed when they're done badly. And I'm disappointed when they're done badly not because I have any proprietary interest in the stuff -- even if there was money involved, which, FYI, there isn't -- but because (a) comics history is young and we need ethical and thorough scholarship to make it grow and (b) there is a small market for books on even popular cartoonists, let alone obscure ones, and one bad book on a cartoonist makes it very difficult for another publisher to wish to release a good one. To think otherwise is naive. Quality does not trump market share. No way. I wish we lived in a world where comics scholarship was not attached to the market, but it most certainly is.

One of the things you talk about in your introduction is how you wanted people to be able to take a fresh look at artists people already thought they "knew," and certainly I was taken aback by how fresh and airy H.G. Peter's work was when shorn of Marston's prose. And I was stunned by John Stanley's "Crazy Quilt," not just because he was doing horror, but that he did it all as a one-person monologue, whereas EC or a more traditional horror comic would have inserted a clumsy flashback. Can you talk a little bit more about how important it was for you to present these artists in a new light and what, if anything, it means to our general perception of comics and its history to have these long-forgotten tales brought into the light? (beyond just having a new appreciation for H.G. Peters I mean)

Well, iconic characters like Wonder Woman and Little Lulu often obscure the actual auteur behind the work. It's a natural thing: You're looking at the icon, not the linework. So I think it's important to look at people who work on such familiar properties -- to allow non-obsessives to see the quality in their work without the confusion of the character. Even I prefer, for example, looking at Jack Kirby's work on non-Marvel stuff. It's easier for me to appreciate without having to see past the baggage.

You stop just shy of the (for want of a better word) modern era in both books, as I recall because you felt that everything past 1970 was pretty well covered by fans and historians and the opportunity to find a book's worth of "undiscovered" artists was pretty slim. Are there cartoonists from the bronze age and beyond that you feel have been ignored to the point where you could justify including them in a book of this nature? And if so, who and why?

A few years back I would have probably shrugged, but these days I gotta answer strongly "yes". But it's an entirely different kind of book. With AOOT I stopped in 1969 because to me that was the year of the paradigm shift: When would-be Fletcher Hanks simply did underground comics rather than corporate stuff -- when the idea of cartoonist-as-auteur was revived and enacted in North America in a sophisticated way. This one stops in 1980 because I was less focused on people operating outside the mainstream and instead stopped before the real burst of 80s publishing.

So ... another anthology would have a lot of explaining to do. For one thing, the cultural context is much less clear, as we don't have the benefit of real hindsight yet. For another, we're talking about primarily a couple generations of cartoonists who came into the medium as fans, reading fanzines, with a certain amount of knowledge about what they were entering into. It's a more insular sensibility. To me, what Frank Santoro does at MoCCA and SPX, etc., is kind of like the third volume: He's hocking Slash Maraud and Thriller and Barry Blair comics next to a Mazzucchelli Marvel Fanfare issue next to a Brendan McCarthy comic. I think if there was another volume (and I don't think there will be) it would need to include a bunch of funky stuff that DC and Marvel published in the confused 1980s, various Marshall Rogers comics, Real Deal, etc. In other words, it's a very difficult book to pull off on a purely logistical level. On the other hand, a totally amazing all indy "black and white glut" anthology assembled by Frank himself would be relatively easy and mind-blowing. Publishers: Call Frank Santoro. He is a great American resource. Also, the dismissal of so much of the above work indicates to me that there's stuff to be mined there -- but would have to be well framed and understood for what it was -- not dissimilar to the 1940s comic book glut: accidental masterpieces and beautiful turds amid the acknowledged classics.

How is Picturebox doing these days? You talked a little bit at MoCCA about Brian Chippendale's new book and what you have planned for the future. Can you talk a little bit on the record about what you've got lined up?

PictureBox is good these days. I've just co-published with FAMILY our first prose book, I Was Looking for a Street, by Charles Willeford. It's a memoir by the great crime writer. We're redesigning the web site as well, in order to offer you, the consumer, yet more stuff.

Let's see...

In a few weeks I'll have a new and very limited edition book by Yuichi Yokoyama for sale only online. It's a $100, signed, and, well, you'll see...

Curating an exhibition at Portugal Arte 10 in July.

Chippendale and CF's books are both (finally, I know!) coming out in September.

They will be joined by:

-A 216-page graphic novel by Renee French called "H Day".

-A collaborative book and DVD by Julie Doucet and Michel Gondry called "My New New York Diary".

-A new 96-page book by Ben Jones entitled "Men's Group/Black Math".

It's nice working with geniuses.

You might ask why I'm not just publishing history books myself? I like to keep things separate and let my brain be somewhere else when doing the history thing. Need to keep things vaguely clean. Or at least somewhat tidy. Etc.

There are some other things coming down the pike but I'll keep a lid on those for now.

FYI, Dan is doing a couple of Art in Time-related events and signings. Below is a short listing of his upcoming schedule

Friday, May 21st at 7PM

Talk/Signing at Desert Island

540 metropolitan Ave, Brooklyn, NY 11211

Sunday, May 30th at 5PM

Afternoon of book signings and conversations with notable cartoonists and filmmakers

611 N. Fairfax Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90036

Sunday, June 26th at 6PM

Talk/Signing

5015 Connecticut Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20008