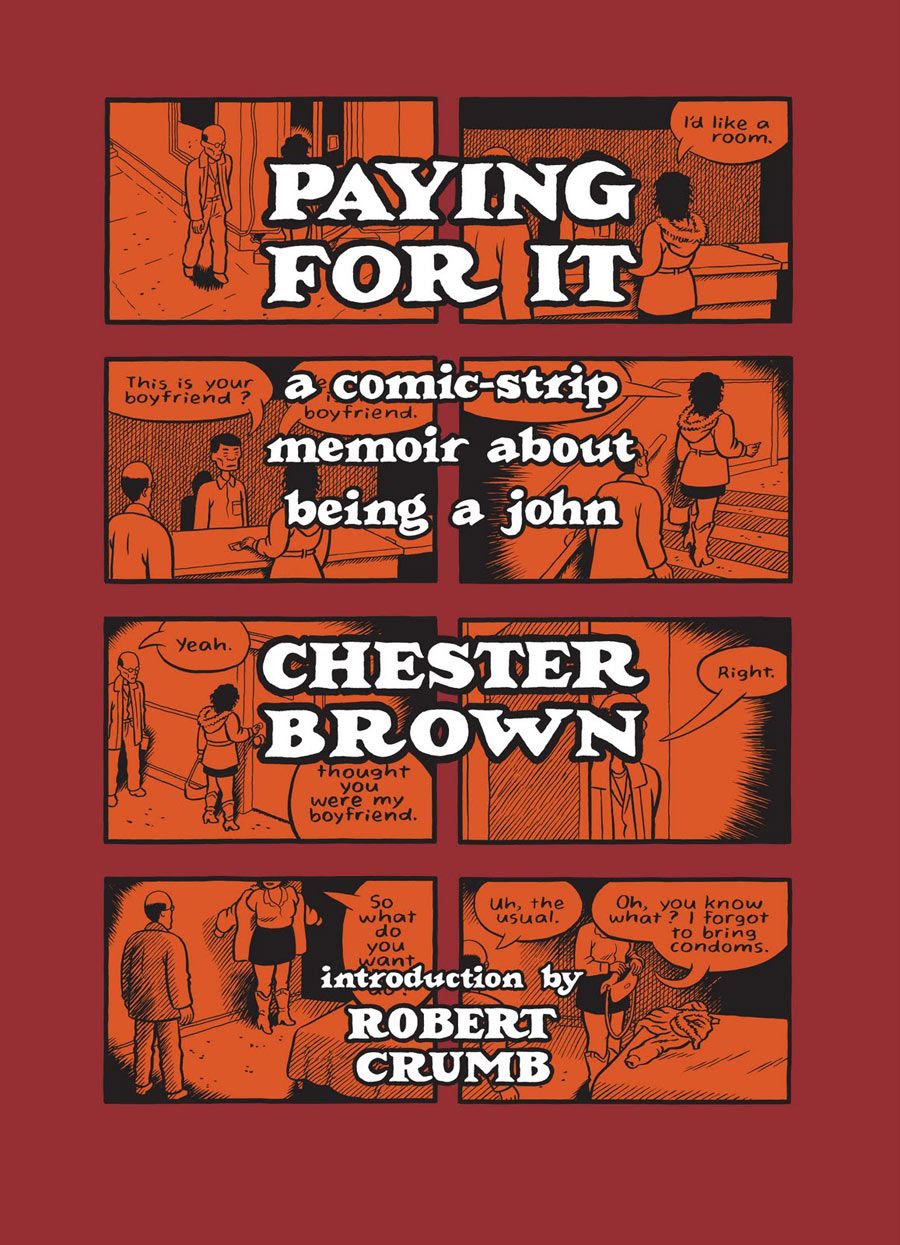

Drawn and Quarterly released Chester Brown's Paying For It: A Comic-Strip Memoir of Being a John in May. It was one of the more eagerly anticipated books of the year, given the skill and reputation of Brown, and it ended up being one of the most reviewed and most discussed graphic novels of the year (so far).

The subject matter certainly didn't hurt coverage any, in fact it's colorful and controversial nature drove a lot of coverage: Brown meticulously chronicles every time he patronized a prostitute between 1996 and 2003, in the process formulating and defending a particular point-of-view regarding the evils of romantic love and relationships and the relative virtues of paying for sex.

Between the first time I read it and the second time I read it (it's that kind of book), I read somewhere around 50 million reviews of it and articles about it and Brown and his position. Two months after release, and all that ink and virtual ink spilled over it, a formal review from me seems kind of superfluous at this point.

Instead, here are a few thoughts about the book...

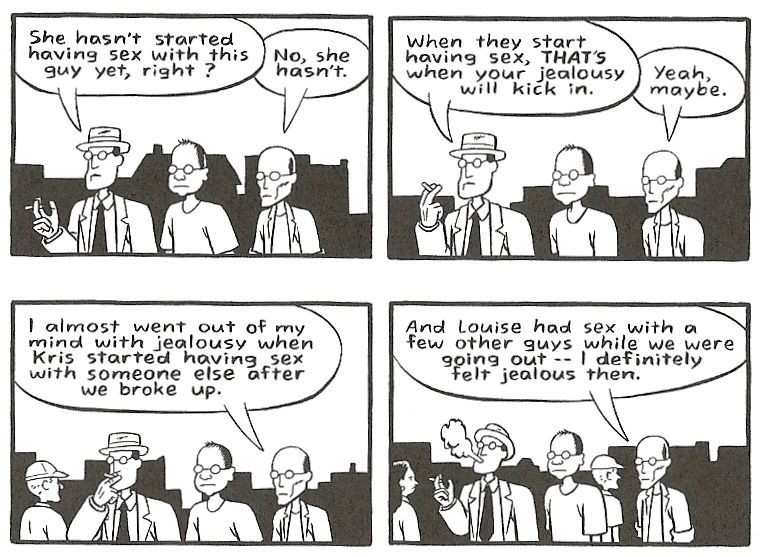

1.) The book opens with the cartoonist breaking up with his live-in girlfriend…sort of. She announces that she thinks she’s falling in love with someone else, would like to try dating that person. Brown gives his blessing, and they decide to keep living together and see where it goes.

Cut to a scene of Brown walking down the street with the little comics avatars of his fellow Canadian cartoonists Seth (Wimbledon Green, Palookaville) and Joe Matt (Spent, Peepshow).

The pair have fairly big roles in the story—Dwight Garner refereed to them as a "wise-guy geek chorus" in his New York Times book review—and when I saw their first appearance, I felt a sudden surge of a mixture of surprise, glee, excitement, recognition and comfort.

I imagine it must be something like what little boys must have felt like reading Marvel Comics in the 1960s, and seeing Spider-Man sudden swing into a Fantastic Four comic, or Daredevil or Dr. Strange bumping into one another on their shared streets of New York City.

There’s something undeniably cool about seeing comic book characters appear where you don’t expect them, or interacting with one another, although it’s a coolness that has been diluted to the point it probably doesn’t even register in superhero comics anymore, given that Superman started playing sports with Batman and Robin back in 1941, and the modern Big Two super-universes are in constant states of crossover (And hell, Archie can meet the Punisher or president or Kiss, and Mr. Spock run into Wolverine or Cosmic Boy).

As cartoonists who are also characters in other comics, Seth and Joe Matt have a peculiar status and, in this narrative, it was the Canadian art memoir comics equivalent of, I don’t know, seeing Johnny Storm and Bobby Drake in a Spider-Man arc, only you’re seeing it for the first time.

The book even rewards familiarity with these characters and their previous adventures, like in a scene where Brown brings up prostitute review message boards, and the Matt character says it’s too disturbing to which Brown replies “How can this be disturbing for someone who watches porn almost 24 hours a day?”

Which isn’t just a quip, of course—it’s practically the plot of Matt’s memoir Spent.

Aside from the crossover thrill, it’s worth noting that the scenes with the other cartoonists are among the most enjoyable to read in the book, because they tend to be the most funny; Brown shows himself debating with himself and friends and even some of the prostitutes (to some extent) about the ethics and morality of prostitution and love, sex and relationships in general, but he’s apparently most comfortable around his friend cartoonists, so those exchanges tend to be the most honest and amusing.

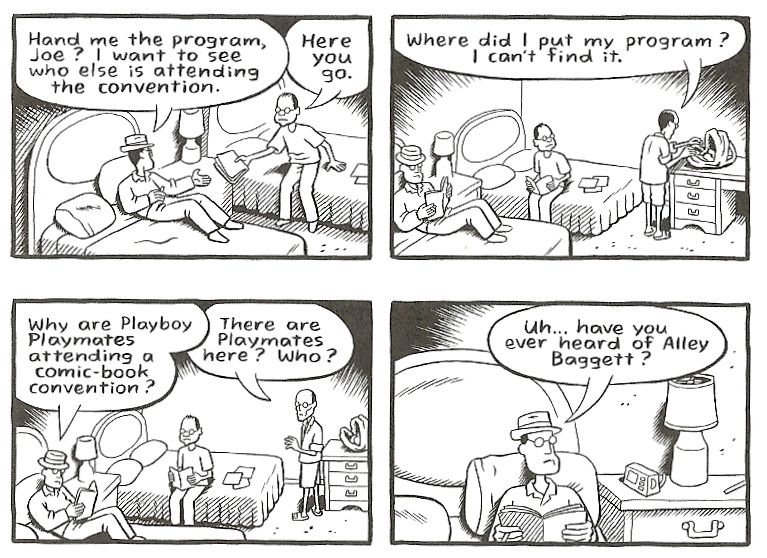

2.) In that same chapter, the trio are hanging out in a hotel room the night before a comics convention, and, looking at the program, they wonder what Playboy Playmates are doing attending a comics convention.

The next day, Brown sees a favorite Playmate, selling hugs, photos and autographs for $50, and though tempted, is too embarrassed by the thought someone might see him (Which is funny, as he puts his thoughts on the subject in this book, so everyone does see him, sorta—the magic of autobio comics!). It’s at this point he thinks, "For another fifty-or-so I could probably pay a prostitute," and his odyssey begins.

It disturbed me to no end to think of these three, each a master of his craft, in a hotel room, at a comics convention, talking about Playmates, one of them even thinking of buying a prostitute.

Because, at that point, I realized that maybe there’s no such thing as comics creator groupies, and that the most talented, most famous cartoonist can’t simply go to a convention and have scores of women throwing themselves at them.

That completely dashed by 40-year-plan, hatched when I was 14 or so, to finally become super-popular with the ladies by growing up to be a famous cartoonist.

Damn it. I should have learned to play guitar. Or even drums! Brown’s last girlfriend left him for a drummer!

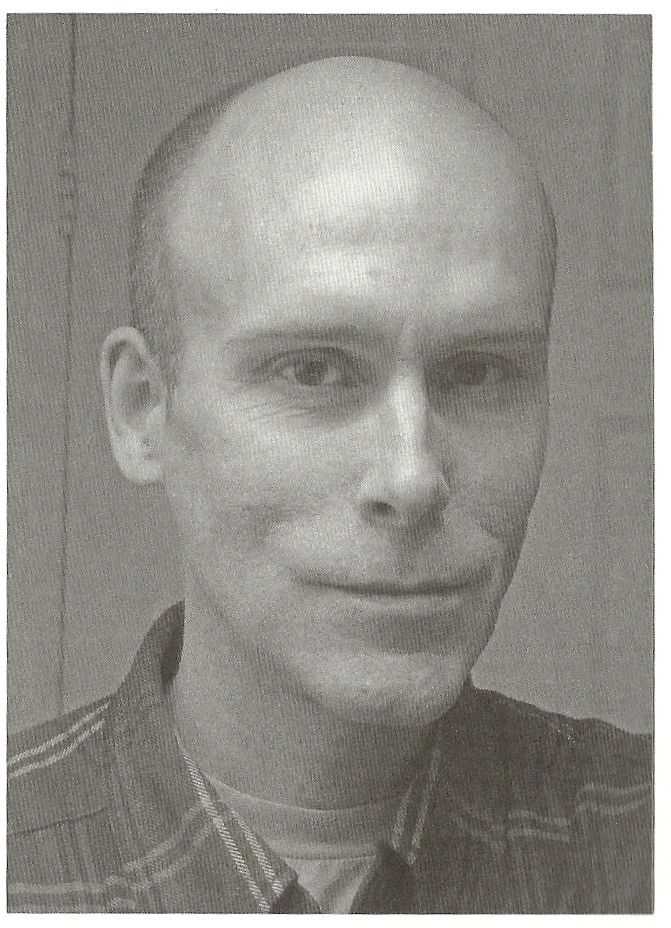

3.) Brown is not a bad-looking guy. Here’s his author photo in the back of the book:

There are even more handsome pictures elsewhere on the Internet. He doesn’t seem like the sort of guy who would have to pay for sex, you know? But then, I guess I don’t really know that many johns in real-life, just the ones I see on various incarnations of Law & Orders, and in the occasional Batman comic, and johns aren’t glorified in either context.

Also, Brown draws himself as a grim, expressionless little bobble-headed skeleton, looking like Harold Grey drawing of the male half of the couple in Grant Wood's American Gothic, so it was kind of surprising to see that he’s not really the undead little goblin I was reading about for the first couple hundred pages, you know?

4.) There’s a very big, very transformative twist at the end of the book, the sort that retroactively colors everything that came before. It’s not actually presented as a "twist," but rather a plot point; it functions like a twist though.

Somewhat frustratingly, seems like the real story—from a dramatic stand-point, if not from the author’s intentions. I won’t say what it is, but…well, okay, I will: Chester Brown was a ghost the whole time! No, I’m kidding, the twist is that he and the prostitutes are really all the same person. No, actually Chester Brown is Keyser Soze, and he made the whole thing up. And "Rosebud" is the name of Brown’s penis.

5.) I really enjoyed the reading experience, and even wrestling with many of the issues Brown brings up in the back of my head while reading, but, months later, I still can’t shake the fact that there was a more interesting story to tell, and that Brown hints at it without getting into it. Maybe in Paying For It II: Pay Harder…?

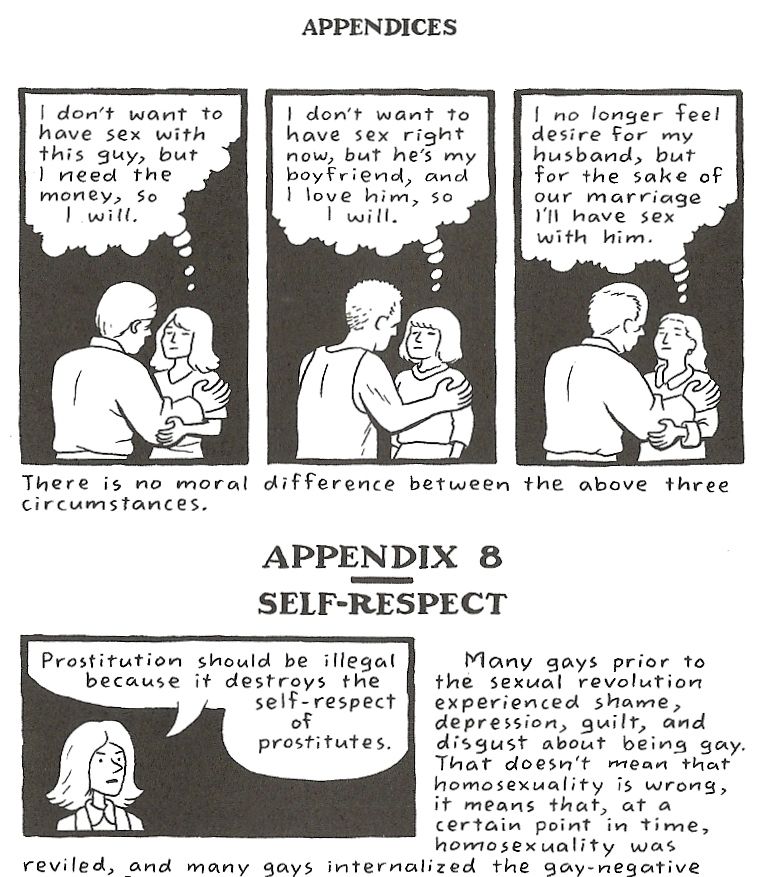

It’s been a few months now, and I’m still not sure how I feel about the 30 pages of back matter, notes and appendices in which Brown expands on the arguments we see made in conversations throughout the book.

They seem sort of foreign to the graphic novel reading experience, but then, it’s Brown’s graphic novel; he can shape that experience however he wants.

It’s inclusion is definitely unusual, which makes it novel, which makes it sort of exciting, a great cartoonist using comics and prose to educate and argue larger social issues…

…but engaging it seems well beyond my job description as a comics critic, and I don’t think anyone really cares about my personal opinions regarding the legality or regulation or sadness of prostitution.

I imagine more readers are more interested in whether or not the book is good and worth reading, and it is at that. Beyond its qualities, it’s also unlike just about any other book-length comic you’ve probably read, which in and of itself recommends it as something to seek out.