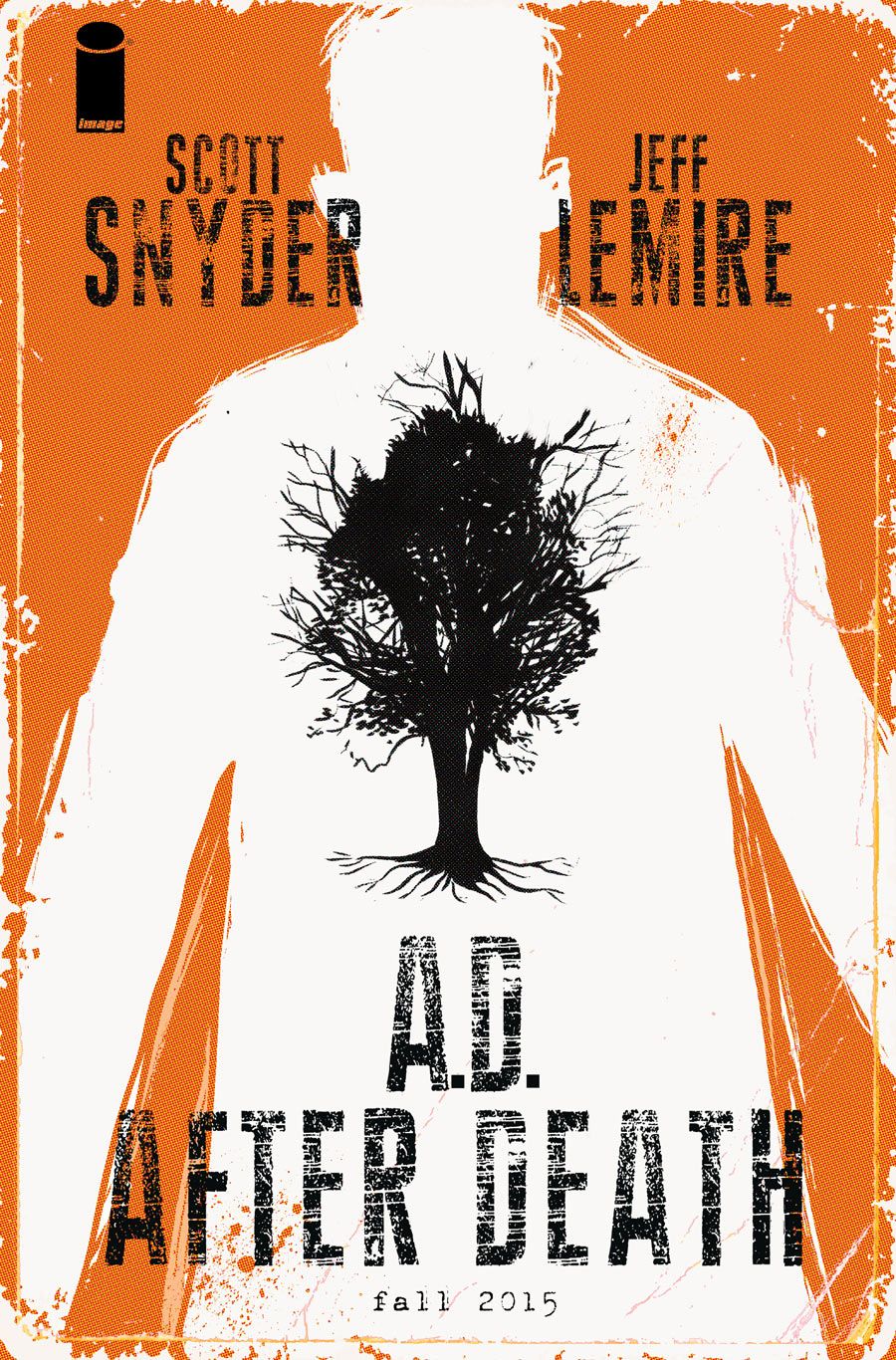

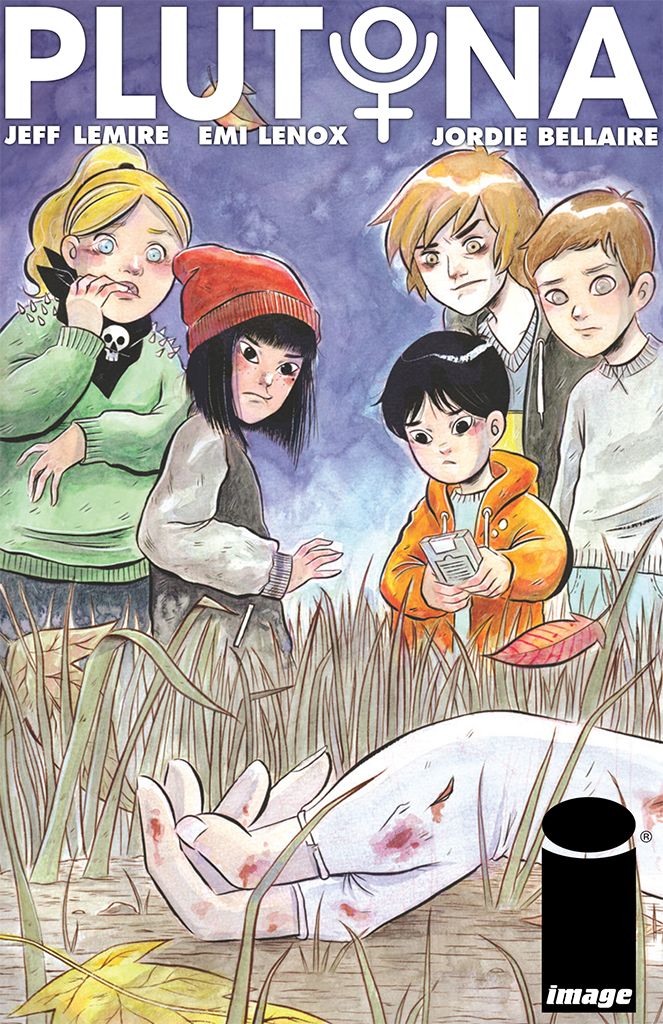

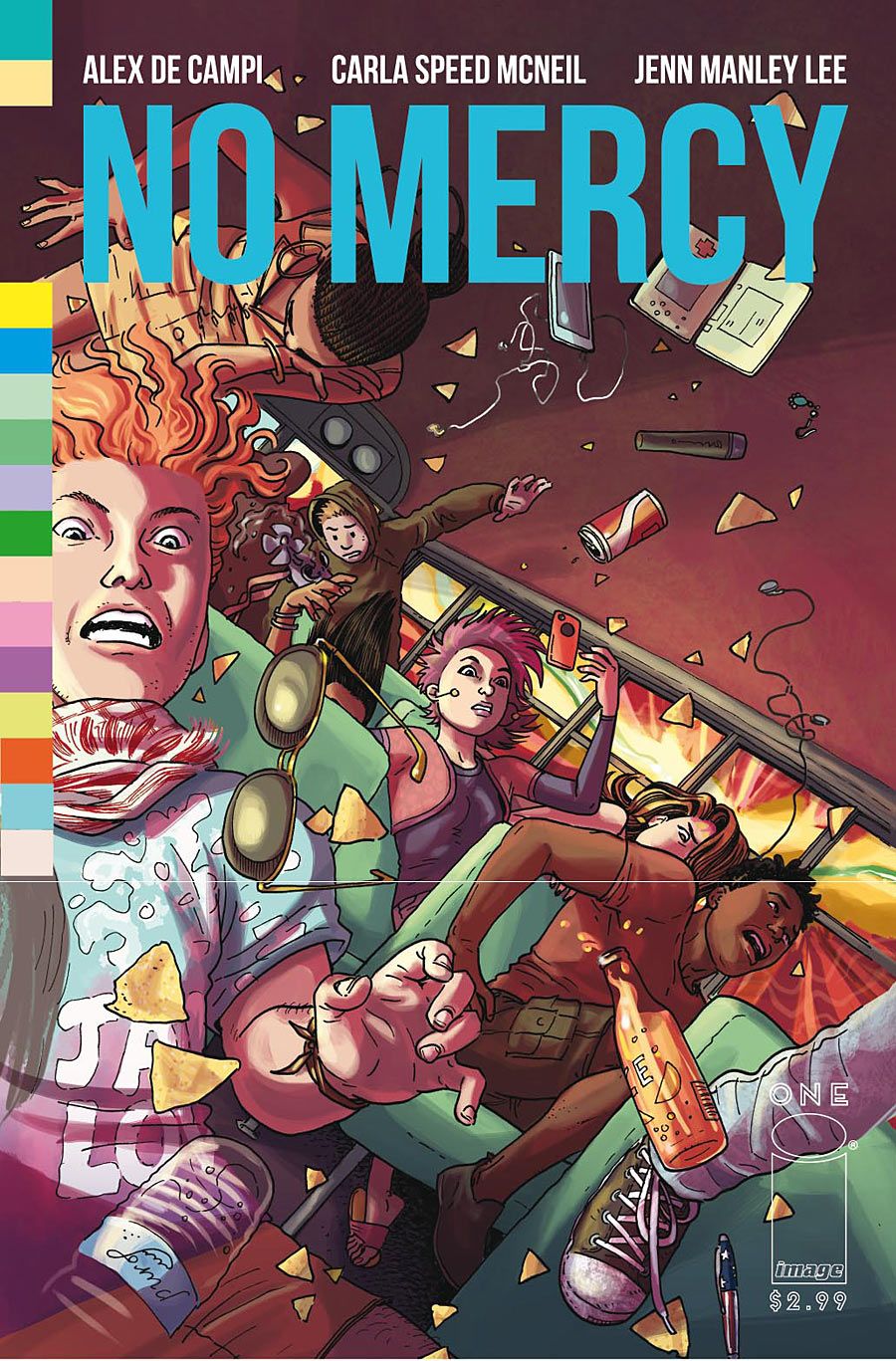

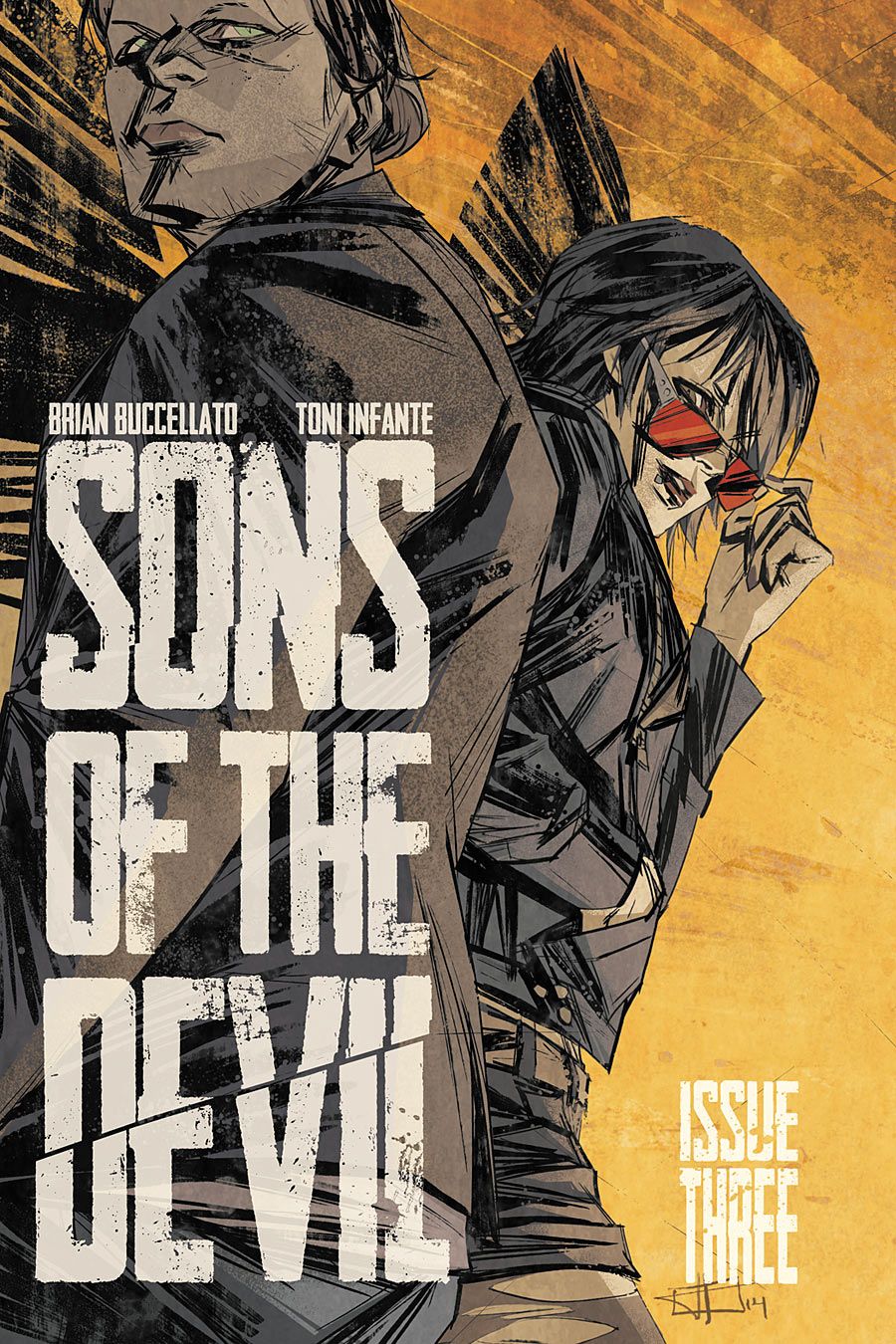

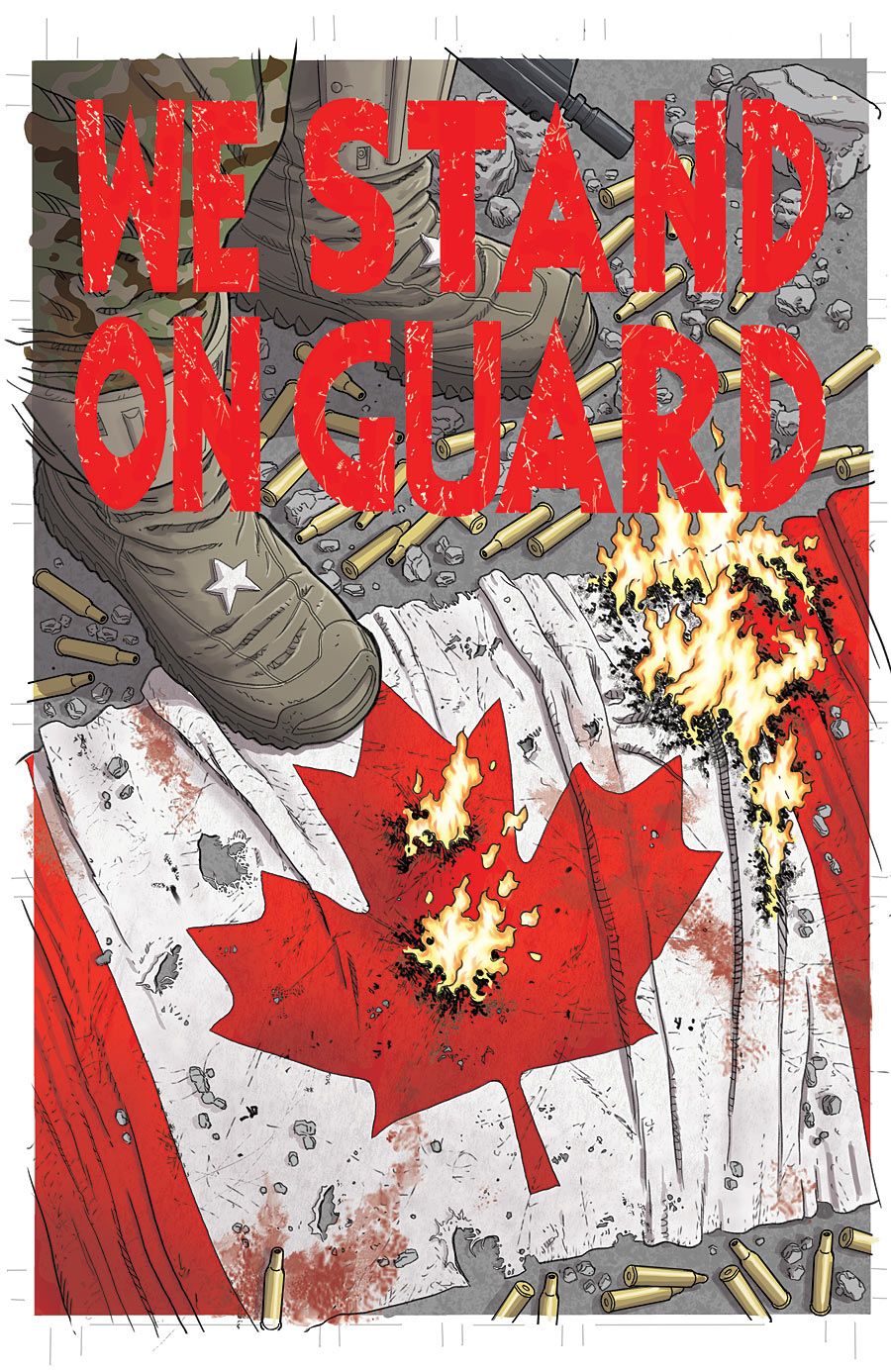

Comic books are a combination of words and pictures, and the form's creativity is only limited by what the writers and artists decide not to include on the page. That type of creative freedom was the topic of discussion when five veteran comic creators familiar with its ins and outs assembled at Image Expo. The "Freedom" panel included writer James Robinson ("The Saviors"), cartoonist Jeff Lemire (the incoming "Plutona," "A.D.: After Death"), writer Brian K. Vaughan ("Saga," the incoming "Paper Girls," "We Stand On Guard"), writer Alex de Campi (the incoming "No Mercy") and writer/colorist Brian Buccellato (the incoming "Sons of the Devil").

Jumping right in, the question was posed to each of the panelists why comic books are an appealing medium for them to tell their stories. "It's a truly unique medium," Robinson began. "It's unlike TV, films, theater. There's a whole set of values to the storytelling rules that you can break and have fun with. Once you get bitten by that bug, it's really difficult to ever let that bug go -- or want to be cured [from] it, I suppose."

"I love film and television," said Vaughan. "But they're so expensive to even do simple TV. Film and TV is show business, with the emphasis on business, and is about commerce first. Then you can fight through for the art. Whereas comics flips that idea on its head, and we have that luxury just doing what we want to do creatively."

RELATED: Vaughan & Chiang on Exploring a "Unique Time of Life" in "Paper Girls"

de Campi later chimed in, "It's lovely to have people not tell you what to do. There's so much in life that in order to make money and survive you have to be told what to do by people who you secretly think are stupider than you. Independent comics are one of the few places where you can have anything you want without any budgetary restrictions or limitations. You can blow up the world, or have a really heart-wrenching scene in someone's kitchen."

Aside from creating comic books, de Campi has a vast amount of creative outlets that she likes to explore. Though she is a lover of music, she is not a musician, but that hasn't stopped her from getting involved. She has directed music videos and commercials, and she described her sense of creative drive to the panel. "I like experimenting," she said. "I think there's two kind of creators. There are people who just do one thing and do it incredibly well and continue to do it incredibly well. Then there are others who do one thing for little while and then decide they want to do something else. I think it all informs each other. I'm a magpie; I like to try lots of different things, and I hope I grow as a creator by doing that."

Lemire, who is more than capable at both writing and drawing, said that whether writing or drawing, all he really wanted was just to tell his stories. "I just got into working at DC as a writer, and that's how I got in. There was no real plan. At the end of the day, writing and drawing is my first passion. The other stuff just sort of happened," he said.

For Buccellato, the question of "Why comic books?" has a simple answer: "Who wouldn't want to work on comic books?"

"It's a rare opportunity that when you get it, giving it up is stupid. I will do comics for as long as somebody will give me an opportunity to do comics." Buccelleto said. In describing his career thus far, the writer noted that he first started as a colorist in the 1990s, having learned from his brother, and then tried his hand at acting. Eventually, he wanted to switch over to the other side of that particular creative process with screenwriting. "I wrote a lot of bad screenplays, but I got better and better. I started writing for a director friend, and that paved the way for me to work at DC as a writer."

That gig specifically was the New 52 re-launch of "The Flash." Francis Manapul, was offered writing duties of that book, but because he didn't have much experience writing, he had asked Buccellato if he wanted to write with him. In turn, Buccellato - already a good friend of Manapul's, as well as his colorist - responded, "Hell yeah!"

As a show of appreciation to Manapul, Buccellato, has a tattoo of his friend's version of the Flash. "I wasn't an overnight success. I earned it over ten years time. I'm not giving it up," he said.

On the subject of discussion was how the writers might change their approach to writing a licensed property as opposed to one of their own creations. Buccellato explained that there are parameters when writing when it comes to the former. "There's a box that you have to operate within," he said. "I don't think that changes a process at all. But there are rules when you're writing Batman versus when you're writing your own version of Batman."

Robinson echoed that sentiment. "I think the ideas can be a bit more unbridled when you're writing for yourself, or less commercial," he said. "But ultimately, the mechanics of writing remain the same."

Following this, Robinson brought up Vaughan and Marcos Martin's pay-what-you-want digital comic "The Private Eye," and praised how the comic uses the dimensions of a computer screen to its advantage. This led to Robinson asking Vaughan whether or not he or Martin has had to impose any restrictions on themselves in the creative process. Vaughan brought up one drawback, though it doesn't necessarily relate in terms of creative freedom or process, but rather the uphill battle of attracting readers to a work that is published only in digital form. "I really think that digital is the future, and most of us will be reading more comics digitally in the future, but the future isn't here yet. Print is still vitally important," he stressed. "It seems like people like to read, particularly comic collectors. They love print comics. So that's been challenging pulling people into a digital only book."

In terms of content, Vaughan said he feels the same kind of creative freedom working on "The Private Eye," as he does on his comics that are set up at Image. "Image is the most freedom that I have had at any print publisher in my life," said Vaughan. "With [our digital company] Panel Syndicate, it's that same freedom -- plus just a little bit more."

However, Vaughan also mentioned there might be times for self-censorship. In turn, the question for the need of self-censorship was posed to the panel. "It's for the good of mankind; you don't wanna know what's in our brains," Lemiere joked. "I've written so much stuff for DC now that I find myself starting to self edit knowing what they're gonna tell me. Sometimes, I have to shut that little voice up."

Robinson spoke of having an instinctive, internal meter for knowing how far to take a scene, even on one's own personal work. "Shooting someone in the face - you can only do that so often," he said. "But if you show it in silhouette or in some stylistic way, an audience can make it much more vivid for themselves in their imaginations."

de Campi added, "Just because you can, doesn't mean you should. Sometimes the best way to leave an emotional impact on someone is to leave something in between the panels. There has to be a valid story reason for everything. That doesn't mean you can't have uber-violence and lots of sex, but you have to have a reason for putting it in."

As the subject turned to how the panelists juggle multiple projects, de Campi grinned as soon as the fan in the audience finished asking his question. "Blind terror," she said. The writer detailed that besides creating comics, she is a single mother with a part-time job outside of comics and is a volunteer at a dog rescue shelter. "The things that you do like watch TV or play video games or go out to restaurants -- I don't do that. I sit, and I write. I take care of my kid and go to my job and answer e-mails about dogs, and that's it."

In addition to writing, de Campi letters much of her own work, so even after the script is done her work on a given comic usually is not. The solution that de Campi has found that works best for her is to keep a rigorous schedule, and then she summed up the whole juggling act with a particularly good example. "You've got the 'wife' project, and then waiting in the wings is the 'sexy, easy mistress' project," she said. "Then also waiting in the wings is the 'other thing that pays the rent' project that you also love."

Buccalleto expressed having the drive to just plain 'ol getting the job done.

"You find the time to do the things that you want to do. I can't imagine anyone being up here representing Image and not wanting to do it. I mean, you find the damn time. Whether it's not sleeping, or whatever you have to do. You wanna write this book; you wanna be here. So you just find the time."

Speaking of having that drive and fortitude to make and create comic books, the panelists were in agreement that they often find themselves inspired by the works of their peers, rather than behaving like it's a competition. Lemire was first to answer, and credited Vaughan's work on "Saga." "When I started reading 'Saga,' that inspired me so much to take more chances and raise my game and start thinking in different ways and pushing myself." He would later add, "Every time I start a big project, it really is a challenge to myself to take another step up in every way -- as a creator, as a writer. It's a personal competition."

Buccellato related that a great story feeds positivity and not the inverse. "I don't feel negative when I read something awesome," he said.

However, Vaughan tweaked perspective. "Bad stuff is really inspiring, too," he said, which drew a few chuckles. "Good stuff might make you go, 'Fuck, I wish I were that good!' But when you read something terrible, you might also go, 'I'm not that bad! I deserve to still be here.'"

Before wrapping up the panel, the creators were asked if their creative process has ever hinged on projecting how readers might react. Buccellato referenced that that can sometimes be the case working for DC or Marvel. "When you work for the big two, absolutely. It usually comes from up above," he said. "I've been told I can't do that, or we shouldn't do that. Or, 'If you do that, the internet will explode.'"

Vaughan said that projecting how an audience might react is a waste of time. "I think it's a losing game to tailor something to an audience. I don't know what your level of education is or what your interests is or your tastes are, so why should I tailor it to this imaginary person?" Then he concluded, "I'm just making stuff that I like and, hopefully, my artist wants to draw."

de Campi outlined that thinking too much about reader reaction wouldn't amount to anything good. "If you tailor to an imaginary audience and what you think they want, that's how bad, mainstream, mediocre TV crap gets made." She finished by saying; "One thing that protects you when you write is that you love the project -- with the undercurrent of terror, of course. Because there's always that. If it flops, you're a little bummed because it can't continue. But you know you loved it, and put your all into it."