Greg Burgas said:

Our very own MarkAndrew is amazed at how poorly written this comic book is, and I'd like him to explain himself!

"Ok," sez MarkAndrew.

And THEN the stupid fucking rabbit all called me out.

But I stand by my guns on this 'un. Despite the love from blog folks here and elsewhere, the Eisner award, the Entertainment Weekly ranking as one of the Top Ten Fiction books of 2005 and all those Publisher's weekly starred reviews Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris' Ex Machina is a deeply and profoundly flawed comic book. Nah... It goes deeper than that. There's a basic ignorance of the craft of storytelling in the first three volumes of Ex Machina that's surprising to see from a professional writer.

In fact, they're messed up enough that I thought it would be worthwhile to take some time to identify at least the really major cock-ups, in hopes that, well, someone can learn somethin'.

So here's my review of The First Hundred Days, Tag, and Fact Vs. Fiction, the first three volumes of Brian K. Vaughan and Tony Harris' finite superhero epic. Some spoilers, but I try not to ruin anything major. Strangely, there's some small spoilers for Gaiman's Sandman too.

.... Insert brilliantly witty segue here.....

2. Stuff that works

Lemme be honest. This piece is a hatchet job. I make no excuses, I make no apologies. I've seen a bunch of unearned and possibly incompetent critical praise aimed in the direction of these books, and I'm repping the other side. I'm being much harsher on these three volumes than I would have been had I not been driven by a burning desire to prove that Declarative Rabbit don't know his carrot stash from his nethers.

But. I do take this blogging think sort of seriously. And I didn't think these three books were all bad. And I don't want any of my writing to be completely in service of an agenda - That way lies madness and turning into Gary Groth, (Or at least Gary Groth when he's peeved.) So the way I see it it's my critical duty to note the stuff that does work along with the bad.

But I'm not gonna waste any time on it! So here's the good review, in condensed bullet point format:

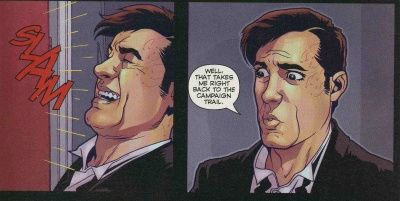

- It's Original! Like all of Vaughan's creator owned work, the basic premise behind this book is very strong. The hero of the book, Mitchell Hundred has a superpower: He can control and communicate with machines. But he's not a superhero in the traditional sense. (Well, usually.) He uses his powers to get himself a job - in this case as mayor of New York City. It's a clever twist on the basic idea of superfolks, and more true to the way the world works than the vast majority of superhero fiction.

- It's exciting! The action scenes are tautly paced and creatively thought out. I'm especially impressed by the superpowered fight scenes. Vaughan shows Mayor Hundred using his powers in interesting ways.

- The cast of Ex Machina is racially, sexually, and..um.. homo-sexually diverse. Score one point for accurately reflecting the diversity of NYC.

- The book's not a comedy, but the dialogue and situations are often laugh-out-loud funny. Better yet, the humor usually arises from the situations the character's find themselves in, and doesn't seem forced.

- The cliffhanger at the end of the first issue was honestly shocking, AND it immediately served to ground Ex Machina's fictional world in reality. (No, I'm not gonna spoil.)

- Not only is the super-powered main character not a traditional hero, but the book is paced faster than most superhero books, effectively mirroring the everything-happens-at-once feel of a good political potboiler.

- The coloring is absolutely spectacular. J. D. Mettler does a hell of a job reflecting the mood of the characters through his coloring, and he uses a differeny palate for flashback scenes than he does for the present day. There's a lot of jumping-around-in-time-via-flashbacks here, but the Mettle makes it all easy to follow.

That's enough of THAT then. But I'm still not quite ready to talk about my major problems with this book. So let's start with a couple of

3. Minor Criticisms

and work our way up.

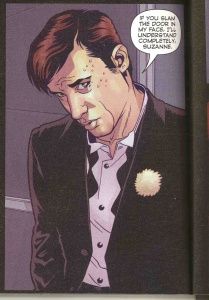

(A) Needs More New York: I've got no problem with HOW things are drawn. The art from Tony Harris (penciller) and Tom Feister (inker) is strong and distinctive. I do, however, have some issues WHAT things are drawn.

Specifically; We need fewer panels of people talking and more shots of the city. At it's core, the book is about the relationship between a man and the city he governs. And we do see the city... sometimes, briefly, in the background or the very occasional establishing shot. But mostly we panel after panel after panel of characters talking about the city, but we we don't have a sense of what it feels like to live in Ex Machina's fictional New York. This is particularly bad in The First One Hundred Days, but it does improve slightly in subsequent volumes.

I can't help but comparing Harris' New York to the "star" of another long running DC series, Robertson and Ellis' Transmetropolitan. Like Ex Machina, Transmet is a politically themed science fiction book, albeit one taking place imm the far future. (Ex Machina is set in more-or-less present day New York.) Robertson's city (called only "the City") teems with life, and Robertson favors us with constant, loving landscape shots, detailing the city from skyline to ground level. And their City was full of PEOPLE, hundreds of 'em, filling every nook and cranny of the background and making us feel... hell, making us SMELL what it was like to live there. Conversely, Harris' New York feels like a ghost town. The only folks who seem to live their are the main characters and a few bystanders sprinkled in to further the plot. It's a city of talking heads, not a fully immersive environment. And in a story that's basically the love affair between a man and a city, that's a major drawback.

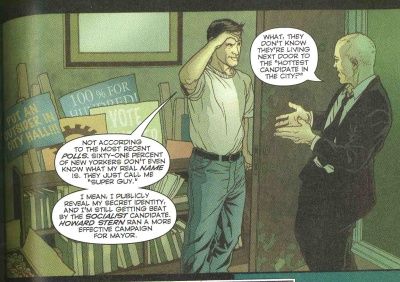

(B) This might be a little unfair but what the hell. I'm gonna introduce a critical standard which I've NEVER heard anybody else apply before. Let's call it Character predictability. It is, however, something I look for in everything I read, and something that bothers the crap outta me when it's not present. Bothers me double in a book like Ex Machina which is a character study, or at least an attempt at a character study. I'd conservatively estimate that Mitch Hundred is on panel 80-85% of the time, and everything that happens in the book relates back to him - an ensemble cast book this ain't.

But IF the book were an effective character study, I think I'd have some sense of who the character is. Fair enough, right?

Here's where I knew we had a problem. Issue 14. Heading towards the end of Fact vs. Fiction. Mitchell's long lost mother calls outta the blue, barely coherent..

"I'm..I'm in a bad way here.... I screwed up bad... But I'm ....I'm so proud of...Nnnnn."

And I had no idea how Mitch was going to respond to this.

No Es BUENO! This far into a character study, I want to feel like I KNOW the character. And that means understanding how the character relates to his family andfriends, and also having a handle on how the character views the world both ethically and morally. There's a few hints; Mitch calls himself a pragmatist, is annoyed by both the stereotypical liberal and conservative views of the world, relates to his staff with a slightly vulgar sense of humor...

Here the character wasn't well defined enough that I knew how he'd respond to this family Crisis. I can tell that Mitch isn't overly introspective, brave, and a man of action, but I don't have a sense of the characters' moral code. And if I don't grok the character's morals, I don't have a firm grasp on what drives the character to do what he does. To steal a line from every shitty actor ever "What's his motivation?"

Dunno.

Having a sense of the main character's moral core is hugely important in a political book. The failure to achieve character predictability is tied in with the lack of character development but the two aren't the same thing. (I'll do plenty of bitching about character development in the next part.) My complaint here is more of a corollary to part A above. The whole Ex Machina world doesn't feel quite fleshed out. We know some stuff about the main character, but not enough that he feels real.

Nitpicky Side-point to this main point: And it doesn't help that Vaughan purposefully (and apparently motivated by no storytelling reasons other than spite) refuses to tell us whether Mister Hundred is straight or gay. This is deliberately left up in the air for the last two volumes. If the writers' gonna play these kind of games - and I'm not convinced they should, ever - they need to make sure that every other aspect of their character is completely well defined, and they ALSO must promise some kind of payoff when the answer's revealed. Vaughan doesn't give us a plot-based reason to care about the characters sexuality by showing that the reveal could have some kind of effect of the series in the future. And if we don't care about a plot point, the space devoted to that particular plot point is wasted. And the time spent re-dredging this useless mystery could be spent moving the story forward. Which brings us to my...

4. Major Concern

First a disclaimer:

I don't think there are any absolute absolute rules in art. Any rule about how stories "should" work should look like a challenge to a real artist, who'll cheerfully go about finding ways to break them. But there are some basic guidelines that writers should be aware of and shouldn't be broken without a damn good reason.

Maybe the most important of them basic guidelines?

Stories should move.

Ex Machina doesn't.

And there's no reason for it.

Between the beginning of volume one and the end of volume three, there's been no change in the status quo, no character development and no major alterations in the thematic core of the series.

On the upside, this wasn't due to a lack of events. Stuff happened. On the downside, I REALLY had to work to care. For instance: There's a bit in The First Hundred Days about a white artist chick painting "NIGGER" on a portrait of Abraham Lincoln, leading to a predictable public freak-out. This isn't a bad plot point, in and of itself, but the resolution of the event rendered it meaningless in story terms. The artist creates a problem, the artist gets a stern talking to, the artist fixes the problem herself, and PRESTO! everything turns out exactly like it was before the problem occurred. "Same," sings David Byrne "As It Ever Was."

ALL the crises, all the stuff that happens... Well, it happens in a vacuum. The end of the third volume leaves off with everybody in more or less the same situation that we found at the end of the first issue. We might know some more background details about the characters, but nothing of any importance has changed. This gives the Ex-Machina-verse a feeling of immutability, and the main characters a feeling of immutability. No matter what obstacles the characters encounter, we can rest assured they won't be effected in any way, be it physically, mentally, emotionally... spiritually...

And that ain't how effective fiction works.

Here comes the rule: There are two ways to make fiction go! forward! - or maybe two degrees of the same thing. Let's hit these one at a time.

Change in the Status Quo can be any number of things. It can be a subtle change in the relationship between two main characters. It can be a temporary shift to a new POV character, like in War and Peace or One Hundred Years of Solitude or Cerebus. At it's most extreme - think David Lynch movies or the Matrix - this can mean that the entire WORLD can change, while the characters stay the same.

Changes to the status quo are how the story refreshes itself. They let the author and the reader look at the basic "what-the-story-is-about" theme-type stuff with new eyes. They keep the story fresh, and absolutely guarantee that the author is not telling the same story over and over.

In The First Hundred Days, Tag and Fact Vs. Fiction changes to the status quo are rare. The location, obviously, stays the same. The status of the characters stays the same - The Mayor and his aids have the same amount of power or status at the end of volume three as in the beginning of volume one, and there aren't any looming problems on the horizon that threaten to change this. Likewise, there's no real shift in the lead characters' physical or emotional status. The only movement in relationship between the main cast is the switch from Mayor Hundred and the his reporter "girlfriend" moving from "completely untrusting of each other" to "slightly trusting of each other but kind of not, too." Worse still, even THIS slight change seems to happen independently of the rest of story. It's not "Mayor Hundred he and his reporter girlfriend get closer because the crazy robot lady went postal and killed the fuck out of a bunch of people." Or even " Mayor One Hundred considers his past as revealed in a flashback, is saddened by his lack of closeness with humanity so he shacks up with his reporter girlfriend."

It's "Mayor Hundred gets closer with his reporter girlfriend... just because." There's no real connection between any series of events in these stories. Stuff happens. Then more stuff happens, completely independently of the other problems that have resolved themselves and vanished, never to be mentioned again. The underlying status quo remains rock solid.

EXCEPT ..

There *is* one major change to the status quo that affects Mayor Hundred in the story, though. But I'm still gonna be critical, 'cause this should've been MORE than a simple Status Quo Shift. It shoulda been a

Revelation.

rev·e·la·tion

/ˌrɛv

əˈleɪ

ʃən/ Pronunciation Key - Show Spelled Pronunciation[rev-uh-ley-shuh

n] Pronunciation Key - noun

The moment when the events of the plot force the character to learn something, and the character is changed forever because of those events.

If a major character is changed forever, this means that the character's view of the events, people, and world around him are changed forever - Which, in turn, means that the character ACTS differently. And if a character acts differently, that means that they're changing and growing... Just like REAL people.

The two most important points here: Revelations should flow from the story, and revelations should offer some kind of payoff which makes the fictional world different post-revelation than it was before. For comparison's sake, let's look at revelation as it's used in the big daddy of long-form, finite, factory system comics: Neil Gaiman's Sandman.

To keep it even, we'll look at the first sixteen issues of Sandman, the same number of individual comics as are contained in the first three volumes of Ex Machina. In these sixteen issues, there are major revelations for the two main characters.

Firstly, the Sandman himself comes to revelation. The first issue starts with the immeasurably powerful Sandman, "The Lord of Dreams" imprisoned in a giant glass box - type thing, with his "Sandman" powers drained. He escapes by the end of issue one, and proceeds to spend the next half-dozen issues gettin' his super-type powers back. (Note: Change in Status Quo.)

After he's back to top shape, he finds himself with nothin' to do. He's bored, restless, iratable... You know the drill. so he calls his older sister. Of course, since HE'S the ancient God of Dreams, she turns out to be Death personified. Granted, she's a happy goth chick and not a fearsome grim reaper, but she's still the woman who moves your soul from the moral coil to onwards. So the Sandman follows Death around for a day, and gets a sense of her dedication, her job satisfaction and the way she tries to make the change-over from funct to de as painless as possible for the mortals she helps cross over. As a result of followin' her around for a day and watching her work, he gains a new appreciation for his OWN job and purpose in life, AND decides it would behoove him to be a little nicer to the people he interacts with.

This sounds like a really simple thing, but his change in attitude has huge consequences throughout the rest of the story (payoff) starting with the very next arc.

Speaking of which - The Doll's House arc, covering issues nine through 16, contains a major revelation for the arc's Point Of View character. She starts out thinking she's a regular human bean, and ends up discovering that she isn't... quite. (Technically she's a dream vortex, and the Sandman almost kills her. Of course, the new improved Sandman does is nice about it. Still almost kills her, though. ) Call this the "Scullery Girl is actually a princess revelation" - Or a character turns out not to be what she thought she was.

But this ain't a Sandman review - Although I'm sure I'll get back to Sandman sometime. But I did want to point out a few examples of revelation as it can be used. (Although it might have been a tad unfair to use Sandman, which is the equivalent to Beethoven's Fifth or the Sistine Chapel of this kinda comics storytelling.)

Ex Machina is short on revelation. There IS one major revelation in Ex Machina - The artist who painted the Nigger Lincoln figures out that she's acting out of spite, not trying to make great art. But as soon as she comes to the "My Life is a lie" point, she's promptly hustled out of the book never to appear again. It's a small revelation, but it's a revelation with no payoff. So who cares?

To Vaughan's credit he does TRY to have a revelation a character based revelation at their core - He just fails to pull it off in any sort of meaningful way.

The major switch is this: Mayor Hundred starts off as a superhero and ends up as mayor.

However he never tells us why. In fact, there's no logical, in-story reason for the character to WANT to go into politics in the first place. In other words: The revelation doesn't flow from the story.

And due to a bizarre structural decision on Vaughan's part, there's no payoff from *this* revelation either.

Structurally, Ex Machina switches between the "now," where Mr. Hundred is the Mayor of NewYawk, and the "then," a of flashbacks showing how he got that way. There is a reason for this approach - it sets up the really cool thing in issue one that I said I wasn't going to spoil. But this flashback heavy narrative style cripples the rest of the series. Stuff that happens in flashbacks is inherently less interesting than stuff that happens in the "now." The main characters that we know and care about ain't gonna get killed or changed in a flashback, so the tension is much less. Every page of flashback is a page that could be used to move the present day story forward. It's not WASTED story, but it's a technique that works best when used sparingly, which obviously ain't the case here. So for the sake of one cool moment in the beginning of the book, Vaughan sacrificesu all the character progression from mayor to hero which SHOULD have been the pistons and other whirly bits behind this storytelling engine. Cause without revelation or much change to the status quo, your story's just gonna turn over a couple times and die. And I gotta tell you folks. These three volumes have the smell of the grave about 'em.

I forget who it was that said it first, but Comics Should Be Good. And not very good comics should not be over-praised. And the thing about Ex Machina is that it's UNIQUELY not very good. I can't think of another long form comic series that has these problems, or at least not one that's designed with an ending in mind.

But maybe there's another reason why I'm peeved. And, make no mistake, reading these books over and over has left me annoyed and disgruntled. These three volumes coulda been really good. Great premise, very solid artist great first issue... But the damn thing just keeled-over-plop soon as it got out of the starting gate. But maybe it'll get better as the series progresses. I flipped through volume four. Didn't read it too carefully because disgruntled, and didn't review it here, 'cause I was already pushing on towards done with my review of the first three volumes. And their was one VERY major change in the status quo, a change so major that it virtually promises some kind of Revelation... Not now. But in Volume five.

Maybe.

But y'know what? Reading and re-reading Ex Machina and picking it apart taught me a lot about what makes fiction good, and what makes fiction bad. Made me a better critic, betcha a dollar it will make me a better writer. So hopefully I'm just returning a favor.