"Huck" #5 finishes answering the questions of Huck's origin, as Huck and his mother are dragged back to Russia and we learn just what sort of experiments both he and his double-crossing fake brother were part of. While Mark Millar and Rafael Albuquerque's comic does so in a reasonable manner, doing so sacrifices the more interesting hook of the previous issues.

Watching Huck deal with everyday life is completely absent this issue, which finds him and his mother trapped in Science City Thirty-Three, aka Naukograd. To be fair, it's almost worth it because of the amazing two-page spread of the city itself, which Albuquerque and colorist Dave McCaig give us at the start of the issue, with its brutalist-styled buildings, bridges and arches spanning as far as the eye can see and delicate flakes of snow drifting down. Albuquerque's envisioning of Naukograd is amazing in its construction, and McCaig's soft, carefully-chosen colors bring the steel gray and olive drab onto those structures perfectly.

However, there's also no denying that having Huck dealing with mad dictators and evil science experiments is nothing like the previous issues. Even last issue, Huck was still taking time out of his search for his mother to help others; there was a real joy to those pages. Here, not so much. While it serves as a strong contrast between Huck's life and what the Russians wanted Huck's life to be, it also makes for a less-than-scintillating reading experience. With the escape not yet completed, it's a safe assumption that most of the conclusion in "Huck" #6 will deal with this too. Now, if we get more "Huck" comics and it's toned like the earlier issues once more, that will ultimately help balance these issues out. For the moment, though, it's ending the arc on a very different note and style than it began, and that's a bit of a shame.

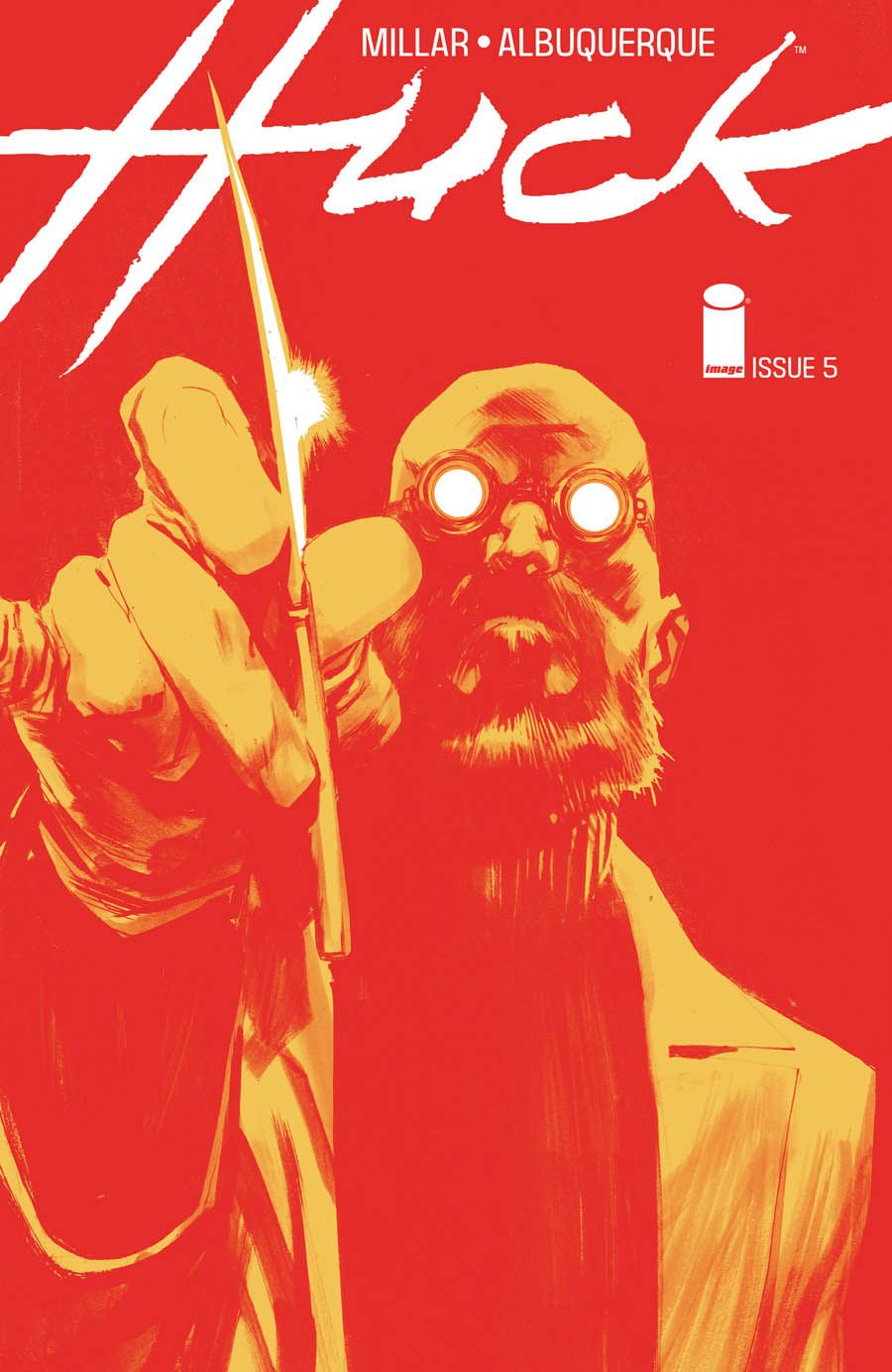

With all that in mind, the plotting from previous issues works well when judged in a vacuum. Huck's idea on how to escape the prison cell is clever enough, and Albuquerque gives that moment a lot of drama. The revelation of just what Huck's "brother" really is comes across as both ruthless and despicable, enough that we probably didn't need the scene where Professor Orlov and XVI execute the Lieutenant to make sure we understood that. It's a lot of exposition here, though, and it does slow down the action that the book appears to be aiming for this month.

Albuquerque's art is very pleasant from start to finish. He's able to bring panic to the Kremlin officer's face, or a calm and thoughtful expression to Huck as he explores the impenetrable wall of the cell. There are a few too many panels missing backgrounds for my taste, although McCaig's ink washes at least keep it from being entirely blank and are certainly pretty. When we do get backgrounds, they're striking. Even something as simple as Orlov's office half-cloaked in shadow is gorgeous, from the old Victrola and the shelves to the arched window over the door, as well as McCaig's orange haze for the light streaming through said door.

"Huck" #5 is a pretty book, but it ultimately feels like it's part of an entirely different series. I'd like to see more "Huck" down the road, but -- while this isn't poorly handled -- it's much more generic than those earlier issues, which really shone in part because of its unique tone. More like that, please.