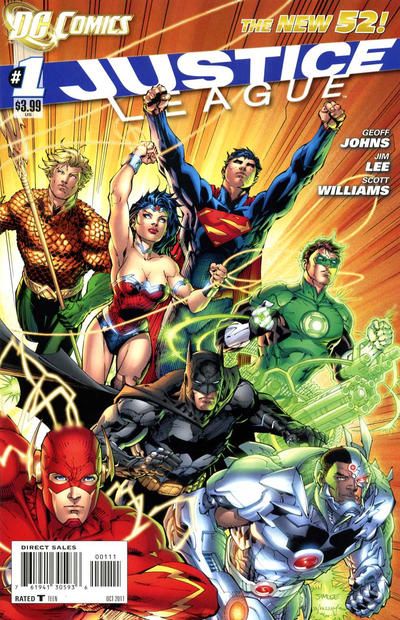

I found Geoff Johns, Jim Lee and Scott Williams’ Justice League #1, the inaugural effort in DC’s "New 52" effort, to be thunderously disappointing. Listening to three months of sustained, daily hype has a way of raising expectations, I guess, and as cynical as I remained about so many aspects of DC’s relaunch, and despite the fact that I took each new tidbit of information with a grain of salt, that much exposure to positive PR still managed to raise my expectations rather high. Particularly for this book, since it was the flagship one, and the one being written by the publisher’s chief creative officer and drawn by its co-publisher.

But the quality of the comic book just didn’t really meet those high expectations.

There are a variety of reasons for this, but one of the most obvious, and one I saw cited most often in the slew of reviews and reactions I’ve since seen online, is that it fails to meet even the most basic, vague promise of its own cover: It’s not a Justice League comic, as the logo says, and it doesn’t features the characters pictured on the front. Two of them star in the book, and two more cameo, but it read more like The Brave and The Bold featuring Batman and Green Lantern…albeit a theoretical version of The Brave and The Bold, perhaps written by Brian Michael Bendis for an eventual trade collection of the first six-issue arc, as DC’s various Brave and the Bold books almost always tell a complete story with a beginning, middle and end in each and every single issue.

While waiting a month or so for DC to dole out the next dollop of their Justice League comic, I thought I’d revisit some previous attempts at introducing a new Justice League to the world in a new Justice League comic. A pattern quickly emerged.

This volume of Justice League is quite different from all previous ones in terms of its slow start. The one it seems to bear the closest resemblance to is the Brad Meltzer Justice League of America #1 from 2006, which spent almost a year finalizing its line-up, but it did feature much of the initial line-up (and the characters pictured on the cover) in its first issue.

How did those other creative teams manage?

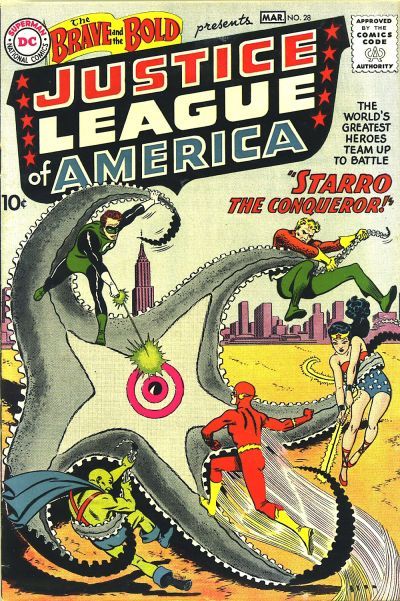

The Justice League first appeared in 1960’s Brave and the Bold #28, in a story written by Gardner Fox and penciled by Mike Sekowsky.

Sekowsky’s now iconic cover featured the five lesser members of the League engaged in a pitched battle with “Starro The Conqueror!”, whose size and big staring eye helped disquise the fact that he was basically just a big starfish (Perhaps if the League had a bigger line-up, he would have been a squid).

It is perhaps unfair to judge Geoff Johns script for this year’s Justice League #1 against a script for a 1960 comic, given how much has changed. From the industry to the audience, from storytelling conventions to product distribution, very little about comics today is analogous to the comics of 1960.

That said, in some ways, Fox’s job seemed even more difficult than Johns’ job.

As his was the very first Justice League story ever, Fox had to introduce the whole concept of the superhero team to his young readers, few of whom would have been familiar with League pre-cursors Justice Society of America. He then had to introduce all seven members, characters the readers would have had some familiarity with, but wouldn’t have grown up with as near-constant pop culture presences the way today’s readers have. And he had to explain why these seven would form a team (it’s not like Silver Age Superman needed a running crew), and wrap it up in about 25 pages. (Where Fox had it a bit easier than Johns was that, as the first, readers didn’t really have anything to compare it against; there weren’t any previous incarnations fans could say they prefer, or rival publishers doing the same thing better).

Fox does it. Not only are all five of the characters on the cover, and the villain they’re facing, in the book, but so too are Superman, Batman and new character Snapper Carr.

The book opens with a splash page featuring all seven characters, a “roll call” that would become a staple for JLA comics, and a paragraph of text announcing the League and it’s goals of stamping out all wrong-doing:

Foes of evil! Enemies of Injusitce! To the heroes of The Justice League of America all wrong-doing is a menace to be tamped out--whether it comes from outer space--from the watery depths of the seven seas--or springs full-blown from the minds of men!

Banded together to fight all foes of humanity, the mightiest heroes of our time battle the menace of...STARRO THE CONQUEROR!

Fox employs the text-heavy scripting of the era as much-needed shortcuts, introducing the characters in narration boxes, having them thought-balloon information to themselves and announce what powers they’re using when they do so, and it gets the job done: If this was the first time you had ever encountered any of these heroes, you’d have a pretty good idea of who they were and what their various deals were by the time Snapper Carr is made an honorary member on the 25th page.

It’s perhaps worth noting too that Fox begins the story with the League already formed. By the end of the veryfirst page, Aquaman is signaling the Justice League of America to warn them of Starro.

The origin of the Justice League wouldn’t be told until 1962’s Justice League of America #9, in a story entitled “The Origin of the Justice League!”

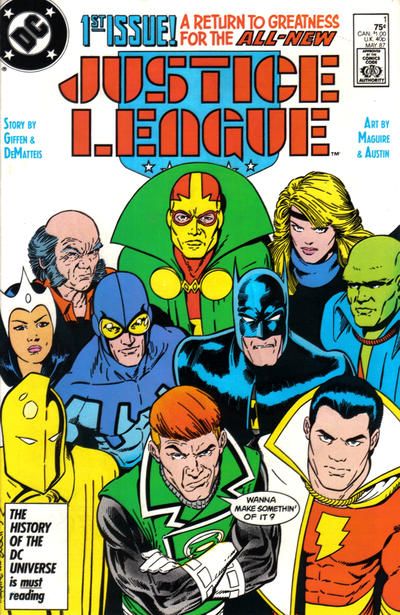

That version of the Justice League stuck around more or less until 1985-86's Crisis On Infinite Earths. Sure, there were some big changes, with characters coming and going, and, the biggest change, the relocation of the team to Detroit and the replacement of some of the original seven with brand-new characters, but it wasn’t until 1987’s Justice League #1 by Keith Giffen, J.M. DeMatteis, Kevin Maguire and Terry Austin that the direction changed radically enough to justify a new #1 issue (something obviously employed much more rarely back then).

Maguire’s cover, like Sekowsky’s first League cover, would become an iconic one, something he himself riffed on more or less constantly since. It featured the entire team striking a pose, and looking up at the reader.

The line-up was a pretty radical departure from either the original concept (“The World’s Greatest Heroes”) or the previous iteration (leftovers from the Satellite Era training new kids), mixing old hands like Batman, Martian Manhuter and Black Canary with characters plucked from the corners of DC’s character catalog, but it was the tone more than anything else that set this iteration of the League apart—it was character driven, it was fun, and it was funny, while (at this early point) still being an action-packed superhero narrative.

This issue also featured everyone on the cover inside its pages (although Dr. Light didn’t appear in costume), and Giffen didn’t resort to a roll call, text page or any shortcuts in doing so. He simply begins the story at the point where all the Leaguers are in the same room at the same time, and then he and DeMatteis introduce them through their dialogue and actions. In fact, by the twelfth page the initial line-up has been introduced, and the team manages to complete their first mission before the end of the book.

How did Giffen and company accomplish so much in so little space, especially since the storytelling conventions of 1987 are that different from those of 2011? (That is, pages weren’t split equally between text and art, and in neither year were there long paragraphs of narration hectoring the reader with information).

Well, I imagine it might have something to do with the fact that Justice League #1 had plenty of pages with eight-to-ten panels on them, and only a single full-page splash, whereas Johns and Lee have a single seven-panel page, with the bulk of the book consisting of three-to-five-panel grids, and four full pages devoted to splashes (a one-page splash devoted to the first appearances of Green Lantern and Superman, a two-page splash devoted to the first appearance of Batman).

Once Giffen and DeMatteis ended their run in 1992, the two Leagues they created would further splinter into more Leagues, and various Justice League books would start, end and rebrand with almost delirious frequency.

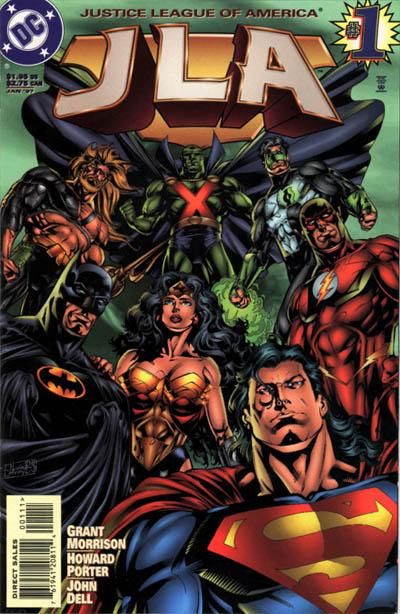

It wasn’t until 1997 that someone would come along and say, “Hey, remember in the 1960s how the Justice League was DC’s A-List heroes in a single book? We should do that again!”

And so Grant Morrison was teamed with artists Howard Porter and John Dell for JLA #1, which reunited the original League line-up, only with Flash II Wally West and Green Lantern Kyle Rayner in for their late predecessors.

Morrison managed to get six of the seven characters on Porter’s first cover into the book (Aquaman was mentioned in the first issue, but wouldn’t appear on-panel until the next issue), and he introduced all six of them rather thoroughly, in terms of who’s who, who can do what, how they interact with one another and even provides a few hints about what their lives outside of costume are like (Here I’m going to point you to Brendan Wright's post "JLA #1 vs. Justice League #1" on his blog The Wright Opinion, where he breaks down the first issue of Morrison and company's first issue, page by page, highlighting all of the new information revealed in each page for new readers).

More importantly, Morrison doesn’t waste time on that introduction, but does it on the fly, with the issue being devoted to a threat. A spaceship lands on the White House lawn, a team of superheroes pour out of it and announce they are here to save the world, and they immediately begin transforming Earth for the better in myriad ways, turning Earth against the old heroes of the Justice League in the process—but something’s up with them, and the League realizes that Earth is actually in the process of being bloodlessly conquered by villains disguised as heroes.

How did Morrison and company get so much done in so little time? They waste far less space on panels and pages than Johns and Lee did, that’s for sure, but there are still a few splashes—a full-page splash introduces the bad guys, and the space ship landing appears on an almost-splash (a small, in-set panel acts as a second panel in what would otherwise be a splash).

They do employ a lot more panels per page than Johns and Lee, but the book is hardly jam-packed with nine-panel grids, with most pages sporting around five panels. The main shortcut Morrison takes is by telling chunks of the story through news reports, a la The Dark Knight Returns. In a sense, the villains’ conquering of Earth is fast-forwarded through via these reports, while the action involving our heroes coming together and interacting with the villains is all dramatized.

And, again, Morrison opens with the League already more-or-less formed (they’re in the process of taking over from the old League in this issue, and won’t get their new headquarters until the end of the first story arc) and already enaged in a serious conflict.

Looking back at Johns and Lee’s opening, then, the main obstacles keeping the issue from being a real Justice League comic seem to be the amount of panels per page, and Johns’ strategy of telling the origin story in a more movie-like fashion, in which everything happens on the “screen” in more or less real-time for the viewer/reader.

The panels-per-page problem isn’t necessarily a problem-problem; Lee’s art is certainly more action-packed than Sekowsky’s, Maguire’s or Porter’s, and the few panels per page is something a generation that grew up on manga can appreciate, maybe even expect—it’s more of an economic problem than anything else. And I mean economic both as having-to-do-with money (Theirs was, after all, a $4 comic book that read like 1/3 of the $2 JLA #1 or 1/10 of the ten-cent Brave and the Bold #28) and story economy; one-issue in, readers have only seen two-and-a-half scenes).

The other problem could have easily been solved by an in medias res set-up, with Johns beginning the story with the League already formed (Most of the other “New 52” books seem to be doing just that, intent on filling readers in on the new origins and/or what has changed and what hasn’t later on). Choosing to begin “Five Years Ago,” and telling the story of How The Justice League Came To Be isn’t a bad choice, or the wrong choice, but it is one that differs greatly from past first appearances of the Justice League, and did contribute to the somewhat unsatisfactory read.

The trade, however, might turn out to be killer. I guess we’ll find out in six-months.