I've been buying a bunch of trade paperbacks, but I'm not really inclined to review them, because let's face it - you don't need me to tell you whether Volume 17 of Ultimate Spider-Man or Volume 8 of The Legend of GrimJack is worth buying (the answer to both of those is "yes"). But what about Narcoleptic Sunday? Ah-ha, that's why you come here! Well, actually, you might just come here to find out what weird things Cronin can turn up and what Bill loves about comics today and probably to mock me, but I will forge on!

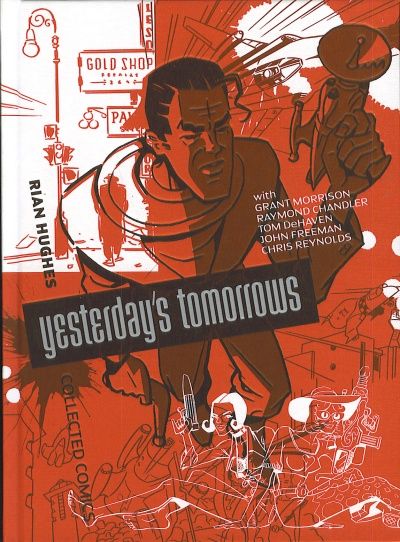

Yesterday's Tomorrows: Rian Hughes' Collected Comics. This is published by Knockabout Gosh and lists at $47.50. You read that price correctly! Let's hope you can find it on Amazon!

Rian Hughes is not really a household name in comics, but he's an excellent and, for his time, a remarkably influential and revolutionary artist. Today his art looks very nice, but we don't really appreciate the style as so fresh and new. This very nice hardcover collects several of his stories from 1987-1991, plus a story from 2003, and it's a neat read. Despite the presence of two Grant Morrison stories, I'm not terribly sure it's worth almost 48 bucks, but if you can find it on-line for cheaper than that, I recommend it.

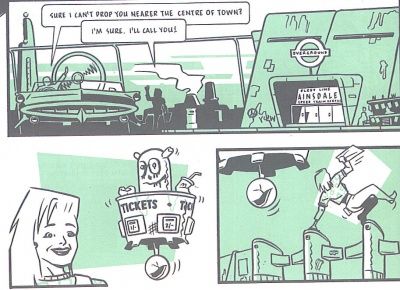

The first story, The Lighted Cities (written by Chris Reynolds), was originally published in 1987, and it's interesting to note how much Hughes changes over the course of the book. The art in this story isn't bad, but it's not as impressive as later on in the book. The coloring is two-toned, with black and khaki filling each panel. It's an odd story, too, more concerned with mood than actually making sense. The second story, The Science Service, is from 1988 and is written by John Freeman, and it shows Hughes' evolution into the retro-futuristic look that he does so well. The story takes place in the future, but a future imagined by someone drawing in the 1950s, and although the art isn't perfect, it does show a nice sensibility that serves him well later on. The color is again a problem, as it's white and teal. It looks good with the 1950s look of the art (teal is probably the official color of the 1950s), but it gets annoying after a while. Freeman's story, interestingly enough, touches on many of the same themes as Morrison's Dare mini-series (reprinted later in thevolume)does - a government more concerned with propaganda than anything else, a company selling a product that might not be safe - but does it with a bit less depth than The God of All Comics does. It's an interesting story, but nothing spectacular.

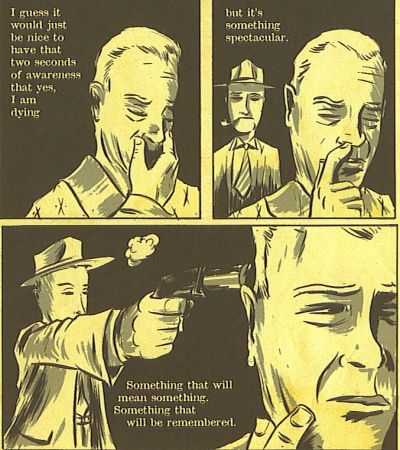

The centerpiece of the volume has to be Dare, the Morrison/Hughes mini-series that was first serialized in England in Revolver magazine in 1990-91 and published in the U.S. by Fantagraphics in 1992. In this series, Hughes does a nice job bringing in his earlier influences but also making England in the future slightly more seedyin addition to the marvelous veneer, and it helps the story immensely. Unlike the earlier stories, where the art doesn't necessarily match the slight rottenness underneath the surface, in Dare Hughes brings Morrison's bleak vision to unsettling life. The magnificence of the structures is contrasted nicely with the decay of the English dream. Morrison's story, about a space hero coming out of retirement to be a symbol of the government until he discovers how nasty that government is, is fairly standard, even though it has the Morrison verve we've come to expect, but Hughes' art makes it a pop art masterpiece. It's a wonderful comic to read, and it's largely because of Hughes, not Morrison, which is interesting.

The other Morrison story, Really and Truly, is more like The God of All Comics we all know and love (except for those crazy people who hate him). It's fairly over-the-top and lacking much subtlety, but Morrison and Hughes keep tossing wacky stuff into it and makes it a joy to read. It's nothing special, but the riot of primary colors and the wild machines and day-glo costumes make it very neat.

The final story in the volume shows that Hughes doesn't restrict himself to technicolor futures that look like a Jetsons episode. Goldfish is a Raymond Chandler story adapted by Tom DeHaven, and Hughes shows that he can do noir as well as anything. The color tones are flatter but no less effective, and he does a nice job with shadows and shading to create a nice mood. His characters are sufficiently seedy, even the femme fatale, and he shifts easily from cityscapes to the drabness of rural Washington state. The story is neat, too, with a lot of twists and a central idea that is simple yet fascinating. It's probably my favorite story in the volume.

Yesterday's Tomorrows is, unfortunately, quite expensive. Even with the stories and the extras, including covers, sketches, and a "Visions of the Future" card set (plus a fantastic photograph of Morrison with hair, combat boots and really tight white jeans), it's tough to say it's worth $47.50. I like the volume, but would definitely suggest you hunt it down for a discount. It's pretty danged neat.

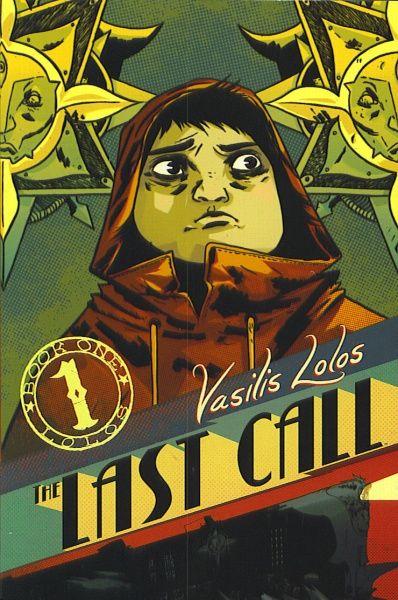

Next on the agenda is The Last Call (volume 1), which is written and drawn by Vasilis Lolos. It's published by Oni Press and will set you back $11.95. It represents a trend that American comics have stolen from manga and I hope catches on; namely, releasing thick books that are part of a bigger story, but still give you plenty of pages and come out regularly, but not on a monthly schedule. This is a nice slice of the story Lolos is planning on telling, and I hope he is able to continue it soon.

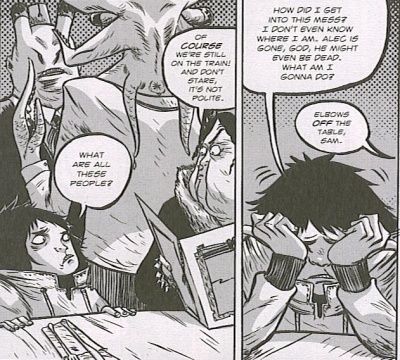

Lolos, I guess, is best known here in America for The Pirates of Coney Island, which he drew. His art is odd and slightly creepy, which fits well with the tone of this comic. He tells the story of Sam and Alec, two punk teenagers who head out one night on a joy ride, smoking stolen cigarettes and listening to atrocious heavy metal (well, the lyrics are atrocious - I can't speak to the music). Their car stalls on train tracks, which of course means a train is coming. Just when they're about to get run down, the car disappears and they end up on the train, which is a very unusual contraption. They are accosted by the conductor, and Alec appears to be thrown out the window because he has no ticket. But has he really been? That's one of the mysteries that Sam must solve as part of the bigger mystery of just what the heck is going on. Then a kindly passenger they had met earlier in the book gets murdered, and his companion, Mr. S, teams up with Sam to figure out that part of the mystery. And the kindly old lady that Sam met is a little too happy to find out that he's a "real live human" as she smiles at him with somewhat less-than-human teeth.

It really is a weird book, but it's very compelling. Alec and Sam start out as punks, and when they're thrown into this bizarre situation, it's fun seeing them get their comeuppance for a bit. Once Alec disappears, however, the book takes a decidedly darker tone, and we find our sympathy shifting to Sam, because the passengers on the train are just so creepy. Lolos does a great job with them, too. Benny is a pleasant fellow, but he is still a freaky-looking dude, and the conductor, whose face is covered by the top of his jacket and an old-style helmet (which looks a bit like a Junker's), crashes about with strangely splayed legs and says nothing but "Tickets." The woman he meets, Meredith, is all jowls and beehive hair, the very picture of a slightly daffy old lady, so when she opens her mouth and behind the regular teeth are rows of sharp shark teeth, the effect is very disconcerting. Lolos does a nice job showing the scope of the train, as occasionally he gives us exterior glimpses of the train and we get a sense of just how big it is. But what is it? Ah, we'll have to wait.

I'm very much looking forward to the rest of the story. And I very much hope that this is the future of American comics. But they won't be if you don't give Oni some money!

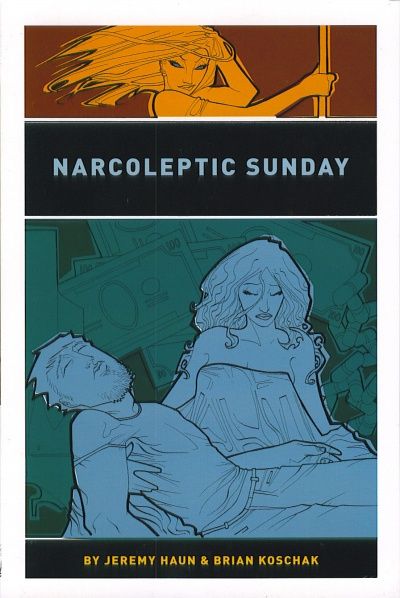

Our next Oni book is Narcoleptic Sunday, which is written by Jeremy Haun and drawn by Brian Koschak. It will cost you $14.95, because it's a bit thicker than The Last Call. It's a complete story, too, in case you're wondering.

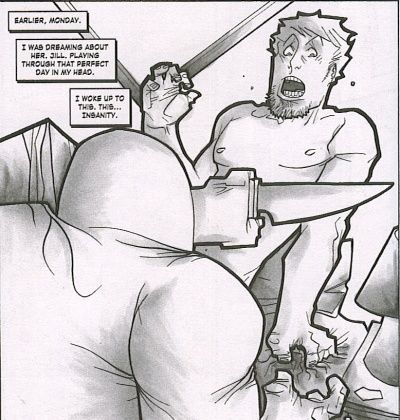

It's not a bad book, but it might only appeal to fans of noir fiction, as it doesn't do much to rise above it. We meet Jack Larch on a bus. On the second page we flash back to Jack in bed with a girl, Jill. We learn they just met ina bar, and end up in bed. Jack explains that he falls asleep at inopportune times, but it's not narcolepsy, it's depression. This is a problem, because after having sex with Jill, he falls asleep. When he wakes up, she's dead and he's been arrested for her murder. There's no evidence against him, however, so the cops let him go. But he can't let it go, of course (or there wouldn't be a book). An old man tells him to trust no one, and then, when he gets home, he has a letter from someone named Gwen who tells him she has a way out of his "uncomfortable situation." Jack decides to meet her, and the situation, as we can figure, spirals quickly out of control.

Jack, like any good noir hero, finds himself quickly way in over his head, and through no real good planning on his part, finds out what's going on. Gwen is a stripper, and her boss, who's quite an odd character, is into buying drugs from dirty cops. Gwen and Jill decided to take some of the money he used for the transaction. Of course, that wasn't a terribly good idea. So now Jill is dead, and everyone is looking for the money she stole. Jack might be the only person who can find it. Of course, he can't go to the cops, because they're crooked. He and Gwen (after sex, of course) figure out a way to get the money. But plans in these kind of stories never go as planned, do they?

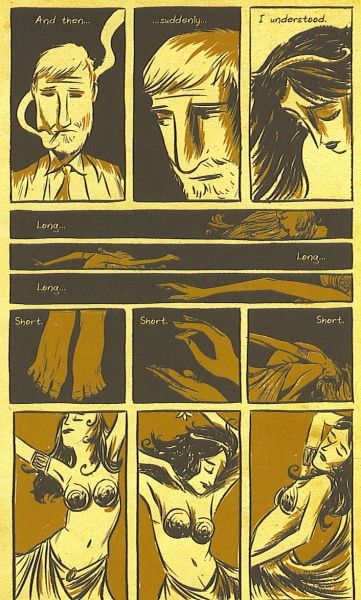

This is a nice twisty little tale, but it doesn't really rise above its genre, which is why it works if you're a fan but won't make you one if you're not. Jack is certainly a classic anti-hero/schlub, who gets taken advantage of at every turn and tries to figure everything out while realizing that everyone else knows more than he does. He's the kind of character you naturally root for, even though he does boneheaded things quite often. It's a well structured book, as Haun does a good job moving the pieces around, and Koschak gives us a good sense of seediness where appropriate. The art conveys the netherworld in which these people live well, and Koschak does a fine job without much detail of making both Jill and Gwen both gorgeous but unique. There's plenty of nudity in the book, just to warn you, but it's not really gratuitous. I mean, people are having sex.

Narcoleptic Sundaydoesn't rise above the genre is for two reasons. Haun's conceit of Jack suffering from inappropriate sleep periods doesn't really add too much to the story beyond the fact that he sleeps through Jill's murder. He falls asleep plenty of times, but it doesn't seem like it's all that necessary for him to be falling asleep. All it seems to accomplish is that he misses some time and has to go around the city at weird hours of the night. Other than the first few pages, it's not like he wakes up in a place he doesn't know or stained with someone else's blood or driving a car, which would have been interesting. Haun uses his condition as a way to kick-start the plot, which is fine, but it could have been used better.

Haun has a nice feel for plot, and his characters aren't bad, but his writing lacks the "oomph" that the book needs. This is his first writing attempt, and he can easily improve. This is also Koschak's first published work (well, according to his bio, "his first time formally in print"), and I am looking forward to more stuff from him. He sets the mood extremely well, his characters are interesting, and his style is pretty unique. So we have a decent book that could be better, but by creators who have a lot of potential.

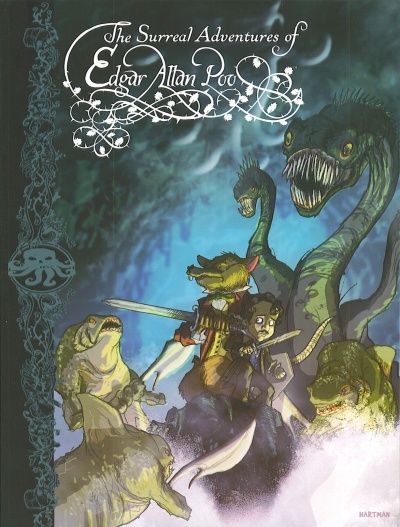

Moving on, we come across The Surreal Adventures of Edgar Allan Poo by Dwight L. MacPherson and Thomas Boatwright. Image/Shadowline published this sucker, and slapped a $9.99 price tag on it. That's not a bad price at all!

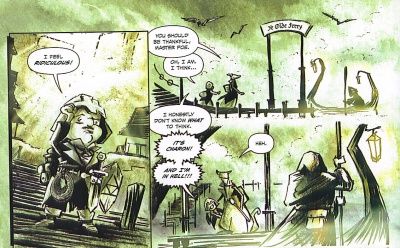

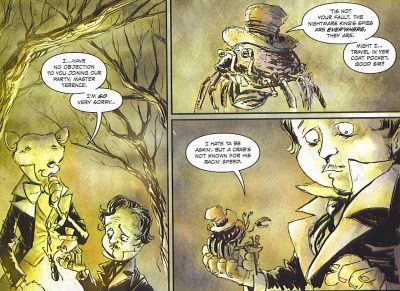

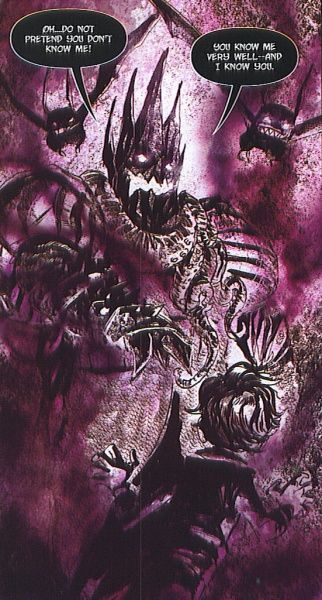

This book is, well,surreal. It begins in an outhouse, and when Edgar Allan Poe exits, he leaves something behind. Well of course he did! Don't we all? Except this time he leaves a little version of himself. Yes, it's Edgar Allan Poo! He meets Irving the rat, who helps him escape from weird bat-like creatures as they flee underground. They enter the realm of Terra Somnium, and Irving plans to take him to the Maghi, where he will discover his destiny. Who is Edgar Allan Poo? Well, this story takes place after Poe's wife died, and he prayed that he would never dream again because he always dreamed of her. Master Poo, as Irving calls him, is his imagination, because without dreams, Poe has no imagination. Back in the "real world," Poe is visited by the ghost of his dead wife, but he is soon convinced that she's a demon. Master Poo and Poe himself get caught up with the Nightmare King, who wants to destroy Poe because Poe has broken his power in the real world. I think. That sounds right. Master Poo must then rescue Poe, or both will die. That ain't good.

That's the bare bones of the plot, but Master Poo's journey forms the bulk of the narrative, and that's where the book goes a bit nuts. The story is your standard Grail Quest, but MacPherson does a nice job keeping it interesting. The scenes with Poe form the emotional core of the book and help ground it, because if we didn't have it, the surreal parts might be too much to take. Virginia, Poe's wife, gets very little page time, butMacPherson creates a wonderful character with alot of depth.

Boatwright does a fine job as well. The art is cartoony, but that makes thebizarre aspects of the story even moreinteresting.He handles the big expansive scenes, as when Master Poo and Irving encounter Poseidon,quite well, and his style easily shiftsto a darker one when the King of Nightmares becomes a major player in the book. The panels are very detailed and create a true imaginative world of shifting landscapes and bizarre creatures, and we have no problem accepting this dreamworld, whichmakes the transitions easier. His work with Poe and Virginia, while still cartoonish, is colored differently in order to make it look more "real," while Boatwright adds some weight to the drawings by doing what looks like a little more actual painting in some panels. The lines are a bit smudgier, too, adding more realism to the pictures. It's a good contrast between levels of existence.

The book ends a bit abruptly, which is really my only complaint. The way Poe escapes the King of Nightmares is explained, but doesn't make a whole lotof sense, and Master Poo's epic comes to a ratherunusual and unsatisfying end. It's strange (surreal, even), because it doesn't seem like it would have taken much longer for MacPherson to write a good ending. I'm not sure what I wanted to happen, but I would have at least liked Poe's triumph to be more obvious instead of being explained in hindsight. That's never a good sign, when another character has to point out what happened.

Despite that, this is an intriguing comic. I would recommend it both for the art and for the way MacPherson takes a real-life event and tries to examine the impact Poe had on the world of literature and how imagination is a fragile thing that cannot be taken for granted. It's an uplifting story, which is unusual when we're dealing with such a depressing figure as Edgar Allan Poe.So that's kind of neat.

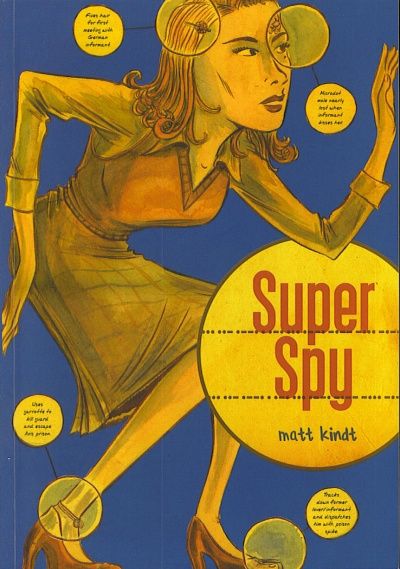

Our lastbook (in this post, of course - they never stop coming!) is Super Spy by MattKindt. Top Shelf published this bad bear, and it costs $19.95. "Parts" of it appeared online between February 2006 and February 2007, but I assume other parts were put in it to tighten up the story. So I guess it counts as an "original graphic novel," and if it does, it's one of the best of the year. This book is phenomenal.

Kindt writes a series of short vignettes that he labels by "dossier" number, which allows him to tell the entire story in a non-linear fashion. The numbering of the dossiers means that you could read this in chronological order if you wanted to, and I might just do that next time. The non-linear format allows Kindt to play with characters, killing some in one chapter and then having them living in a later one, and it's fun to patch together the timeline from what we know. It's a neat way of structuring the book.

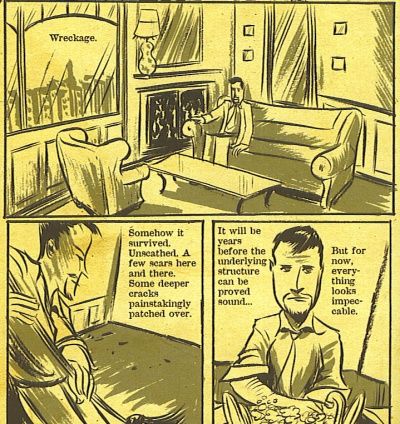

The book is about World War II spies and the lives they lead. There is very little glamor, but a lot of danger and double-crosses and people trying to eke out a life on the margins of the great conflict. Each story is very short, highlighting a particular point in the spy's life, when their mission goes horribly wrong or they complete the mission successfully or they discover something important. Early on, the vignettes don't seem to be connected, but a pattern gradually evolves, and certain characters reappear and push the narrative forward. Ultimately, the Allies are trying to stop the Nazis from developing an atomic bomb, but that's really just window dressing. The main interest of the book is in the characters.

Kindt shows, without making it too obvious, the desperate lives these people lead. We see a woman who will do anything for her baby. Another woman swims across the English Channel just for revenge on the man who killed her family. A spy crashes in a remote area and ditches his mission, falling in love and raising a family. But will the English allow him to get away with it? A comic strip writer plants codes in his work and is dragged into more dangerous work. A man who just wants to get his mother out of France and into neutral Spain is struck by a car and finds that it changes his life. And through it all, the most dangerous assassin in the war stalks, turning up in the unlikeliest places and killing with impunity. The book is full of sudden violence, small moments of tenderness, and acts of bravery and desperation. It's a wonderful look at people who have many different motives for spying, but ultimately want only to get out any way they can. Some do, and some don't. It's fascinating to see how the survivors manage it.

Kindt's art is beautiful, as well. His work is a bit fantastical, which works well in the topsy-turvy world of 1940s Europe. However, he grounds it with excellent details in the backgrounds and down-to-earth characters. He useshis art to create a worldof falsebottoms, hiding places with poisoned spikes in them, and shadowy back alleys where clandestine meetings take place. Hispeople are often out ofperspective, taking up too much of the panel or shrinking down to nothing, showing up as X-rays to reveal where they've hidden plans or how a knife enters their body, and running through harrowing streets with soldiers on their tails. Kindt's colors are wonderful. The firststory is colored in sepia tones, giving theSpanish streets a light and airy feeling, until everythinggoes wrong. From there, he delves into darker tones to match the stories. When one spy heads to Cairo, he's back to browns, evoking the desert. When anwriter/artist of children's books plants codes in the pages, Kindt colors the story with bright primaries. And when the war ends, the colors reappear, giving a feeling of rebirth. It's a beautiful book to look at as well as read.

I really can't recommend this book enough. It's exciting, it's interesting, and it hasgreat characters. It shows the lengths people will go fight evileven if they'reterrified. It shows great heroism and human failure, as well. And, at over330 pages, it's a fantastic value! You know you want it!

Well, that's itthis time around. I know it's tough to shell outducats for big honkin' books when the monthlies cost so very much, but I hope you found something youmighthave an interest in. There's somuch good stuff out there!