"Hawkeye" #14 by Matt Fraction and Annie Wu chronicles Kate's first adventure out in L.A. With the exception of two loose threads that tie into larger plot lines, "L.A. Woman" is structured like a one-issue short story, with conflicts and a small mystery resolved in twenty dense pages.

Fraction's plotting approach is slow to address overarching, ongoing conflicts, but his "day-in-the-life-of-Hawkeye" stories are so satisfying that readers are not frustrated about being kept in suspense about, say, exactly what the Bro Gang's deal is. Fraction is able to keep these villains on the back burner because they are largely beside the point. "Hawkeye" is more focused on character and comedy than on showing the heroes getting the better of the villains. At the same time, "Hawkeye" always sports an upbeat and celebratory tone. The title's heart is in Fraction's approach to superheroism, which is Small-Town-Apple-Pie conservative, bright-eyed and unshaken in its belief in goodness.

Fraction' script also rewards close reading. It is dense with sly, ironic and playful jokes on each page, such as Kate's declaration that she's "pretty much an Avenger" and a send-up of contemporary blurb text on food labels. Fraction takes pleasure in peppering the speech of Flynt Ward with words like "constabulary." The plot takes unusual sideways twists in Kate's open-ended interaction with the hilarious and mysterious Cat Food Man at the grocery store and how she finally deals with the villain of the story by goading him commit a new crime, instead of proving him guilty of alleged crime that is the catalyst for the action. The Kate Bishop in this story is goofier than the confident Hawkeye who worked with Clint, but she no longer is Clint's foil, and her bumbling around suits the story and her new girl in the big city status. The story in "Hawkeye" #14 dips into mawkish sentimentality near the end, but in a self-aware, hipster-ish manner.

Once again, Fraction combines an indie-comic-like enlargement of a grind of domestic, everyday concerns (about things like making rent money and caring about the neighbors) with brightly-colored costumes and a chipper attitude. Martin Scorsese coined the term "smugglers" for a certain category of directors. A recent New Yorker film review by Margaret Talbot talks about this category of auteurs: "they work in commercial movies and work in established genres, but within those borders they slip in a secret cargo of personal preoccupations." Fraction's storytelling on "Hawkeye" qualifies him as a smuggler; "Hawkeye" can be compared to both "American Splendor" and classic "Spider-Man", while also being obviously its own thing.

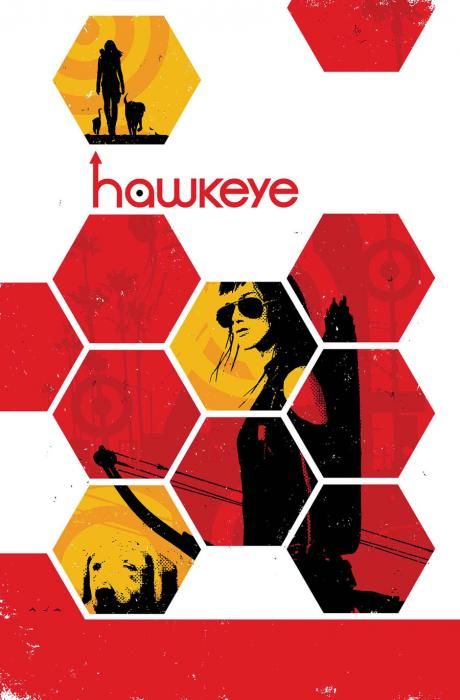

Notably, "Hawkeye" #14 is also is Annie Wu's debut on "Hawkeye." She has an insanely tough act to follow, as David Aja's name is nearly synonymous with "Hawkeye," but her work here is excellent. She has less of a spectacular overarching design sensibility than Aja, but equal attention to composition, and her more expressive line that makes her faces and backgrounds less abstract and more fluid-feeling than Aja's. Wu's backgrounds are lovely, and she is wonderfully selective with detail, using only slim vertical lines to indicate books in shelves.

Her details also enhance Fraction's humor, especially in the pinched face, prissy body language and puffy ascot of Flynt Ward.

Her line combines well with Matt Hollingsworth's colors, which are saturated and flat, joyful and attractive as usual, shifting in hue and intensity to match scene content. Their combined efforts make the last page of "Hawkeye" #14 a grand tableau. Fraction's plot revelation here is an old move, but Wu and Hollingsworth give it force. The red/black/gold of the servant is perpendicular to the cornflower blue/orchid pink and white of the bath. Wu's composition focuses the reader's attention on the important facts with a minimalistic but expressive line. The details are lovely, especially in the panes of the windows and the shape of the man holding an antique phone with a cord that drapes into a graceful J-curve.

It's a dramatic, well-executed ending for "L.A. Woman," which meets the book's standard of splashy yet casual excellence.