It was forty years ago today that the world got slightly sillier: Today marks the 40th anniversary of the airing of the first episode of the seminal sketch-comedy series Monty Python's Flying Circus on October 5th, 1969. Greatly beloved by nerds everywhere (God only knows how I'd have gotten through middle school without my two-cassette copy of The Final Rip-Off), the troupe—comprising John Cleese, Graham Chapman, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Terry Jones, and Michael Palin—has a deeper comic-book connection than simply the shared interests of many of its fans. For starters, there's their send-up of Superman in the sketch "Bicycle Repair Man," which takes a Twilight Zone twist on the Superman concept and plays it for laughs:

Cleese would return for another stab at the Last Son of Krypton in Superman: True Brit, a collaboration with Python biographer Kim "Howard" Johnson and artist John Byrne.

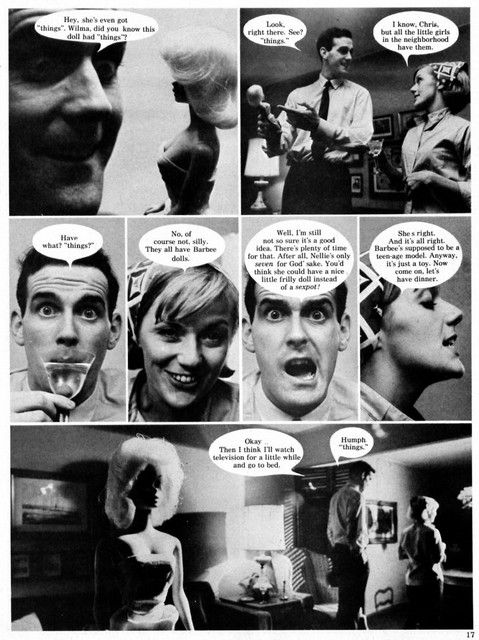

But the Pythons' greatest contributions to comics and cartooning come from its sole American member, Terry Gilliam. Today, Gilliam is best known as the live-action director and bane of the studio system responsible for fantastical films like Brazil and the upcoming The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus (the late Heath Ledger's last movie, not to mention one of several directors who took a crack at a Watchmen adaptation before Zack Snyder. (Gilliam abandoned the idea, saying the book was unfilmable.) But Gilliam got his start in professional comedy by doing comics and fumetti for MAD magazine founder Harvey Kurtzman's mid-'60s humor publication Help!. (Gilliam penned a must-read tribute to Kurtzman for the Telegraph in July.) It was in Help!'s pages that Gilliam first collaborated with his future fellow Python Cleese in a still-funny photocomic called "Christopher's Punctured Romance," about a man who falls in love with a doll.

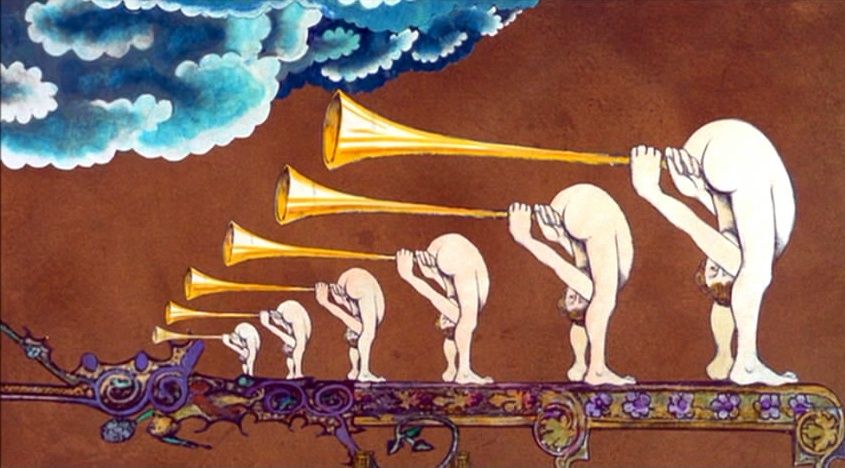

Gilliam's main contribution to Monty Python was as a cartoonist. His often-imitated, never-duplicated animation work gave the show its credit sequence and much of its visual signature. Combining sampled art (medieval, Renaissance, Victoriana, vintage ads), his own underground-influenced pencils, a healthy dose of surrealism, and a fourth-wall breaking wink-wink nudge-nudge at his own budget limitations, Gilliam's animations perfectly captured the Python style—both brainy and bawdy, and totally unpredictable from one moment to the next. The "Killer Cars" sequence from Python's greatest-hits style movie And Now for Something Completely Different is a representative example:

But perhaps my favorite Gilliam cartoon is the deceptively simple, gloriously stupid "Conrad Poohs and His Dancing Teeth":

The influence of Monty Python is as inescapable in comedy circles as the Beatles' in pop music, and their cartoons cast a long shadow over humor comics and animation to this day. Without them, everything from John Kricfalusi's Ren & Stimpy to Michael Kupperman's Tales Designed to Thrizzle to the entirety of the Adult Swim programming block would likely be, well, something completely different.

For more on Gilliam's work as a cartoonist, check out this essay by Noell Wolfgram Evans.