Poor reviews and mediocre box office for the Green Lantern movie, and news that aspiring genre films no longer need Comic-Con, may be combining to signal the end of America’s love affair with nerd culture. However, Super 8, director J.J. Abrams’ tribute to the Steven Spielberg movies of his youth, celebrates nerdity in a few different ways. Protagonist Joe Lamb is a middle-schooler in the summer of 1979 (a summer when yours truly was transitioning similarly from fourth to fifth grade). He collaborates with a filmmaking friend and does makeup for the latter’s amateur movies. On one bedroom wall is a poster of the yet-to-fly Space Shuttle, and on another is a reproduction of Detective Comics #475's “Laughing Fish” cover (by the great Marshall Rogers and Terry Austin, of course). He builds model kits, and not just so they can be blown up for an inexpensive visual effect. Obviously I recognized a lot of myself in Joe, and just as obviously, I was not alone. More importantly, though, Joe’s nerdity is endearing, not off-putting. Contrast that with Green Lantern’s fidelity to its source material, which reinforces the expectation that superhero comics must lead rookies through mazes of dogma more easily navigated by longtime fans.

To be sure, Super 8 has a few significant advantages over Green Lantern. First, it’s a better-made movie, introducing its characters and grounding them in the plot so clearly and precisely that those mechanics feel almost rudimentary. (Of course, it helps that Super 8 plays mostly in the real world of small-town 1979.) Second, although it is so careful with the details of its setting, in terms of the big picture Super 8 isn’t as concerned with those details as Green Lantern is. Joe’s most important characteristics are his relationships with his parents, not that he’s working on a Hunchback of Notre Dame kit or that he’s a comic-book fan. While the trappings of Green Lantern don’t look exactly like Gil Kane or Joe Staton drew them, the movie still wants you to know it tried to do them justice.

Third, Super 8 grounds Joe’s nerdity in his adolescence, whereas Green Lantern gives Hal a certain man-child quality. Hal does mature over the course of the movie, accepting the awesome responsibility that the ring carries (and learning to harness his willpower along the way). Still, because Green Lantern is an origin story, Hal only comes completely into his own at the end. By contrast, Joe begins as a more fully-formed character whose emotional journey involves dealing with unexpected trauma, not new responsibility. In this regard Joe’s nerdity -- or, put another way, his “secret knowledge” of arcane matters like modelmaking and science fiction -- is incidental to Super 8’s plot; while Hal’s whole journey is about learning a particular kind of secret knowledge. Therefore, it is arguably easier for an audience to accept Joe, the kid, as a nerd, than it is for them to watch the adult Hal’s induction into the byzantine Green Lantern Corps.

Now, this is an obtuse way of saying “Green Lantern should not have been an origin movie,” and although I just said it, I don’t think GL’s origin-story plot was entirely wrongheaded. The basic Green Lantern Corps backstory is elegantly simple -- a group of immortals selects thousands of courageous beings for its intergalactic peacekeeping force -- and within that framework, an individual Green Lantern has a lot of leeway about how to keep the peace. No matter who it is, a given Green Lantern won’t necessarily have the same agenda as his/her/its colleague(s), and a Green Lantern may also be at odds occasionally with the Guardians. The Guardians themselves should elicit some probing questions, namely about the nature of their governance, the derivation of their authority, and the ability of their agent(s) to interpret that authority.

Longtime Green Lantern fans will recognize those issues as concerns raised in Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams’ seminal “Hard-Traveling Heroes” arc, when Hal questions his role as the Guardians’ representative. When I reviewed Green Lantern its opening weekend, I mentioned those stories as a good foundation for a different kind of GL movie. Indeed, the choice between Terran morals and ancient, otherworldly ethics was played out over thirty years ago as the climax of 1978's Superman, when Supes chooses to ignore Jor-El’s edicts so he can save Lois’ life. Superman could make that choice, at least in part, because he only had to answer to an artificially-intelligent version of his late father. Hal, on the other hand, must either work with the Guardians on an ongoing basis, or give up the ring.

In fact, the Guardians aren’t always distant and out-of-touch, as John Stewart’s introduction in GL vol. 2 #87 demonstrates. Although Hal objects at first, a Guardian orders him to give John a ring and battery, and Hal eventually learns to see past his initial impression. This story comes fairly late in the O’Neil/Adams run, so readers familiar with preivous issues will have seen Hal’s social consciousness expanding, thereby making them somewhat sympathetic to him going into #87. (There’s also the fact that they’d be sympathetic just by reading Green Lantern....) Accordingly, Hal’s acceptance of John isn’t seen in dramatic terms as a punishment or other comeuppance, but as further evidence of Hal’s emerging social awareness.

The problem is that, in the current conception of Hal’s journey, any instance of self-doubt -- especially from the “hard-traveling” stories of the early ‘70s through the gray-haired period of the early ‘90s -- has been retconned into the chinks in Hal’s emotional armor which allow the Parallax fear-entity to take control. The Hal purged of Parallax, and brought back to action in Green Lantern: Rebirth, is apparently free from self-doubt; but this has made him confident to a fault. It’s not as noticeable as it might be, because Geoff Johns’ plots haven’t given Hal much room for reflection.

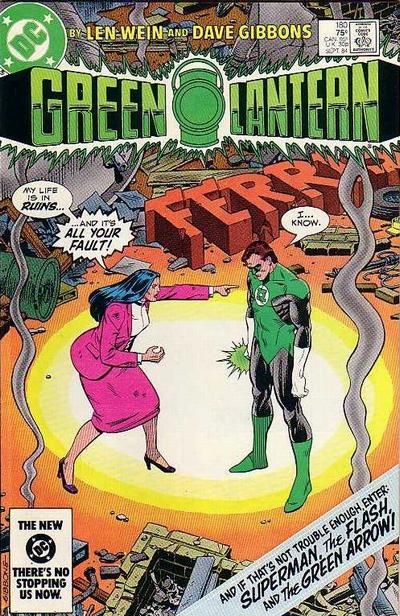

By implication, though, it denigrates the various attempts by Johns’ predecessors to give Hal some nuance. The relaunched Green Lantern could get by on stalwart superheroics in DC’s Silver Age of the 1960s. In the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, though, Hal needed something to distinguish himself -- not just from other superhero books, but (as time went on) from colleagues John Stewart and Guy Gardner. After O’Neil’s tenure ended in 1980, writers Marv Wolfman and Mike Barr exiled Hal from Earth; Len Wein had him quit the Corps; Steve Englehart brought a squad of Lanterns to Earth; and Gerard Jones planted the seeds for the Guardians’ apparent betrayal. Ultimately, none of it was enough, and Green Lantern jettisoned all of its mythology in favor of the last Guardian choosing Kyle Rayner as a singular Green Lantern. Now Earth’s four Green Lanterns can be described rather simply as the Dreamer (Kyle), the Soldier (John), the Hothead (Guy), and the Leader (Hal).

The Green Lantern movie brings everything full circle, bringing the modern conception of Hal back to his beginning, giving him just enough doubt to be dramatically appropriate (and, perhaps, to lay the groundwork for its own Parallax subplot), and otherwise betting heavily that viewers will like the mythology as much as they (ostensibly) like the hero. Again, this bet isn’t a longshot: I thought the movie mostly did right by Oa, the Corps, and the Guardians. Still, it’s a lot to absorb, especially when the plot also incorporates Hal’s relationships with Carol Ferris, Tom Kalmaku, the extended Jordan family, and even Hector Hammond. I suppose it’s a bit of poetic justice that, like Hal himself, the Green Lantern movie struggles to balance Earthbound concerns with fantastic outer-space adventure. Accordingly, it falters when it fails to ground Hal’s experiences in a recognizable character arc.

See, the thing about Green Lantern is that magic ring + steadfast hero = fairly generic superhero setup. The details can be compelling, but by themselves they don’t add up to a fully-formed story. Instead, the best Green Lantern tales are rooted in a particular ring-slinger’s unique approach, whether it belongs to Hal, Ch’p, Soranik Natu, or Mogo. Imagine that Robert Smigel/Jack Black script re-worked to feature G’Nort in more of a tall-tale setting. More to the point, imagine a movie picking up with Hal in his post-Ferris career, trying to balance terrestrial mundanities like shelter and employment with his GL responsibilities. That may sound like a Spider-Man plot; but again, the difference is that Hal could easily be a full-time Green Lantern, giving up his Earthly life entirely. (John did it in his Mosaic solo series, and both Hal and Kyle have left Earth for extended periods.)

The point is, the comics offer many GL-movie possibilities which can stay faithful to the original stories without alienating new fans. Treating the Guardians, the Corps, and/or the ring’s rituals as incidental to the plot, and not necessarily integral, frees the filmmakers to focus on larger concerns of character and spectacle. The movie’s scenes with the Corps assembled on Oa are a good example of this -- plenty of Easter eggs for fans, and an exotic, otherworldy vista for the general public. Maybe an audience skittish around nerd culture shouldn’t realize it’s actually learned something about said culture until it’s too late.

There’s one last difference between Super 8 and the average superhero film that I feel compelled to mention. Usually, when my wife and I leave a movie which is based on a minutiae-heavy, decades-old work, she will have many questions; and I tend to spend a good bit of the drive home on the answers. With Super 8, however, I had the first word: “See, model kits are cool!”