DC Comics is calling June “Superman Month,” but next week is Snyder Week. The first issue of Scott Snyder and Jim Lee’s Superman Unchained arrives next Wednesday, and the premiere of director Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel premieres in most places two days later.

Therefore, because there will be a lot of Superman talk coming down the pike, I thought I’d get mine out of the way early.

* * *

One thing that comics blogging has taught me is a healthy respect for the roles (including the rights) of creators. Creators’ rights aren’t unique to comics, of course, but you really can’t talk about the history of superhero comics, or the development of corporately handled superheroes, without at least acknowledging the people who first introduced the concepts. In this respect Superman is a special case, because he seems to have developed past his creators’ original idea (or, certainly, past the original parameters) into something Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster might never have imagined -- and people seem pretty cool with that, in a way that perhaps doesn’t apply to similarly long-lived characters.

In the context of their larger histories, we consider the “sci-fi Batman” or the Bob Kanigher/Ross Andru Wonder Woman to be anomalies, far removed from what Bob Kane and Bill Finger or William Moulton Marston and H.G. Peter started out doing. More particularly, we can see where specific creative teams decided expressly to get back to basics. With Superman, though, the differences come not just from expansions of the core concepts, but from a general extrapolation of the character into The Best, Period -- with no significant push to roll anything back. Today we remember Siegel and Shuster’s original stories for Superman’s social conscience and two-fisted approach to the problems of the day. (We might also remember that around this time, his powers and supporting cast expanded when the feature branched out into other media.) Similarly, we see the Mort Weisinger era as having traded those primal impulses for an explosion of wild ideas and an establishment-oriented viewpoint. When Julius Schwartz succeeded Weisinger in 1971, the Superman books tried to blend all that lore with a more “modern” sensibility; and generally, that approach has stuck.

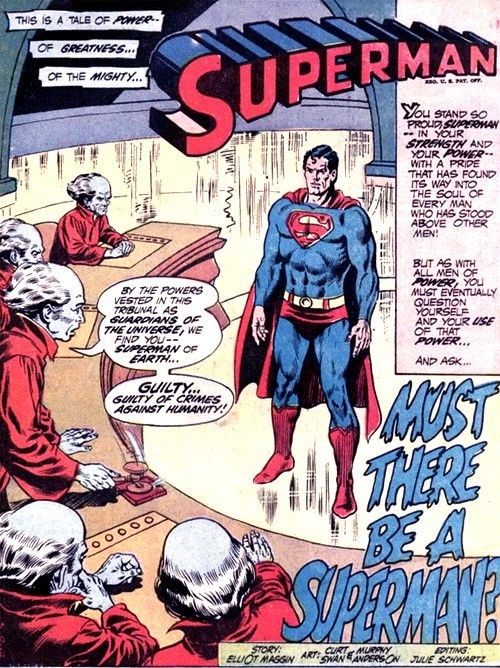

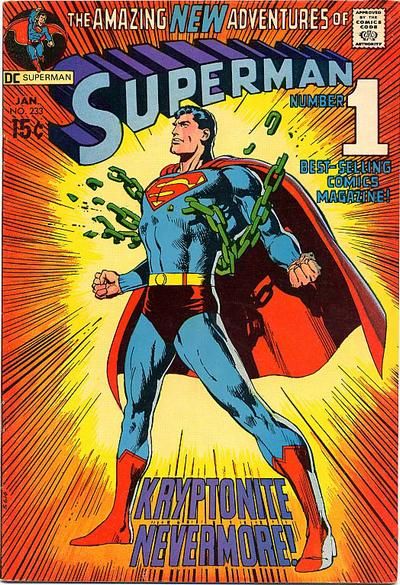

Accordingly, from the Schwartz era forward (if not before), fans and pros alike have tried to determine “what Superman means.” When all of Earth’s Kryptonite was rendered inert in Superman #233's “Superman Breaks Loose” (January 1971), the pragmatic Morgan Edge reminded readers that absolute power corrupts absolutely. A year later, January 1972's Superman #247 asked the seminal question, “Must There Be A Superman?”

Today, though, I am wondering, “must Superman mean something?” After all, we seem content not to compare Batman, Aquaman, or Green Lantern to Jesus, and the socially-conscious aspects of Wonder Woman (a more messianic figure, if you ask me) tend to vary with the particular creative team. Not so with Superman. The Orson Scott Card controversy didn’t go to the merits of the author’s story, but to the intersection of his homophobia and the unvarnished goodness that Superman has come to represent. (And I say that not to defend Card, whose views I find abhorrent.) For better or worse, Superman’s characterization has become almost indistinguishable from this deeper meaning -- or, if you will, the need for such meaning.

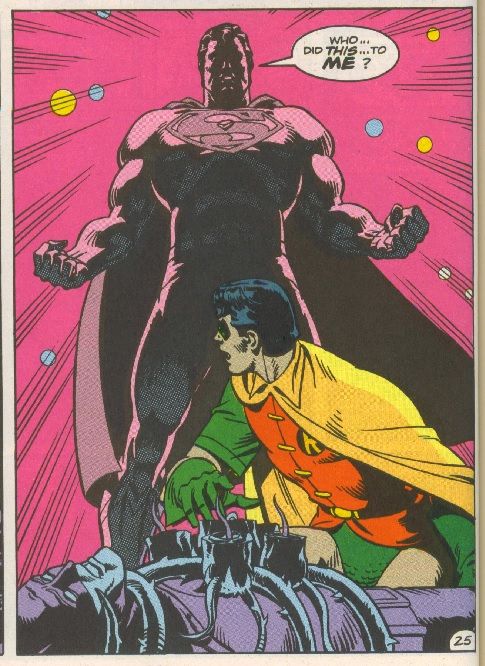

Of course, then there are stories like Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ famous “For The Man Who Has Everything” (1985's Superman Annual #11), where Superman’s characterization is divided between a not-quite-ideal fantasy of Krypton and the Total Beatdown Mode of his battle with Mongul. The latter is “Superman breaks loose” in a fairly literal sense. (The “Who ... did THIS ... to ME?” panel even duplicates Neal Adams’ famous pose from a pants-wettingly low angle.) Supes calls Mongul “vermin,” lays into the would-be conqueror with air-igniting heat vision, and throws punches that register on the Richter scale. This is Superman when he doesn’t have to be a nice guy. He resists the Black Mercy because he knows his fantasy should never have happened, and therefore his inherent goodness causes him to “sacrifice” it -- but honestly? What with reactionary Jor-El and the civil unrest he’s helping to foment, it’s not really the perfect fantasy. As a result, the point of the story is not so much that Superman abandons his heart’s desire, but that Mongul gives it to him and thereby earns his wrath. To be fair, Moore’s “Whatever Happened To The Man Of Tomorrow?” (in May 1986's Superman #423 and Action Comics #583; penciled by Curt Swan and inked by George Pérez and Kurt Schaffenberger) did center on Superman making a critical choice based on his particular code of ethics, so the two stories complement each other fairly well.

Now, this is not to malign “FTMWHE,” which is well-constructed (if a bit reliant on ironic panel transitions) and makes good use of that wacky ol’ Weisinger-era lore. Indeed, part of the appeal of “FTMWHE” is its relative lack of complexity. Moore wants Superman to be heroic, but he doesn’t couch that heroism in any ethical choice that might challenge the reader. Instead, he creates a showcase both for Superman’s powers and for the intergalactic diversity represented by lost Krypton and the menageries of the Fortress of Solitude. It could be Batman fighting the Scarecrow through the Batcave, Wonder Woman fighting Doctor Psycho across Paradise Island, or the Flash taking on Gorilla Grodd in the Flash Museum. It’s a good story, and it happens to be a good Superman story.

However, these days we hold Superman stories to higher standards, because the character himself has come to represent a nebulous set of lofty ideals. In that regard, I can’t help but think that the notion of Superman as an aspirational figure has colored both fans’ and pros’ perspectives. To put it bluntly, I don’t think Superman is a Christ figure. It’s a convenient shorthand that really glommed onto the character sometime around the first Christopher Reeve movie, and to me, it doesn’t fit. To say Superman is Jesus implies that Superman has all the answers. That can be very comforting, but it can also put people off, and besides it may make the character less interesting. The texts tell us fairly consistently that Clark/Superman’s morality was shaped significantly by his time on Earth, and particularly by his foster parents, regardless of how the particular creative teams viewed Kryptonian culture.

Therefore, while Clark may reflect the Kents’ shared ethics, and may be guided by them, he doesn’t take that further into any kind of evangelism. He may lead by example, although he may not consider himself a leader. Mark Waid and Alex Ross explored this aspect of his personality in Kingdom Come; and in his 1978 novel Superman: Last Son of Krypton, Elliott Maggin tried to summarize basic ethics with the phrase “there was a right and a wrong in the Universe, and that value judgment was not very difficult to make.” This informed the Kryptonians, the Guardians of the Universe, and Superman himself. It also drove home the point that Superman doesn’t advance any particular credo, just the nominal, common decency which underlies any “good” behavior.

Naturally, we could go further, but for our purposes it’s sufficient to note that Siegel and Shuster may not have intended the Kents to have been as big an influence. Until John Byrne’s 1986 revamp, Krypton’s morals were fairly similar to Earth’s. Krypton’s destruction was a tragedy, but Byrne emphasized that maybe it was more of a blessing in disguise. His Krypton was a cold, technocratic society that might well have conquered Earth with a super-army. (In a 1990 arc, the implacable Eradicator relic almost accomplished this single-handedly, by acting through a mind-controlled Superman.) Thus, “the Kents’ influence” becomes a rationalization for Superman’s character, not a fundamental part of his conception. Today’s Superman may owe his ethics to his foster parents, but for Siegel and Shuster, all that may have mattered was that he was ethical.

Now, I’m not saying Superman shouldn’t have a strong code of ethics, or that he shouldn’t be an aspirational figure, or that he shouldn’t set an example for his colleagues. I just wonder whether the emphasis on his “purity” has yielded diminishing returns. The Superman of Kingdom Come started out in self-imposed exile, created a quasi-totalitarian society, and had to be reminded of his basic humanity. He went from abdicating his leadership role, to abusing it, to learning how to temper it with humility. Kingdom Come has its flaws, but it remains a good example of a story which explores Superman’s ethical struggles without exploiting them.

Indeed, sometimes I wonder how much we need to do to justify Superman’s altruism. Readers readily accept that yellow sun + Kryptonian cellular structure = flying and laser eyes, but unselfish behavior apparently requires a little more suspension of disbelief. The issue of “what does Superman mean” has given way to “Superman always does the right thing,” and that risks putting the character in a box. The basic question should be, if Superman can do anything (like the song says), what does he choose to do?

The answer should depend on a sense of Superman as a person, not necessarily as an ideal; and should derive from the appropriate narratives, not from an externally-imposed “need to be good.” Superman Unchained and Man of Steel offer the latest opportunities to explore what drives the world’s first superhero, and I’ll be curious to see how they go about doing it.