I talked about it last week, but there’s a lot to unpack in the recent Williams-and-Blackman-leave-Batwoman imbroglio. Part of it is DC Comics' apparent need to keep characters relatively unchanged, which these days includes being young and unmarried. Co-Publisher Dan DiDio has already explained this in terms of heroic sacrifice, so I suppose that’s as close as we may get to official company policy on the matter.

However, before DiDio made his comments, I was wondering whether DC didn’t want the non-costumed half of Batwoman’s main couple to remain single and uncomplicated. After all, Maggie Sawyer goes back further than Kate Kane, and has appeared in both the animated Superman series and in Smallville. Thus, a certain part of the TV-watching public probably associates Maggie Sawyer more with Superman than with Batwoman; and DC might not want to have her tied permanently to the Bat-office.

This, in turn, brings up the issue of DC as a “content farm,” providing material for future adaptations. Obviously the publisher has almost 80 years’ worth of characters and stories ready to provide inspiration. Indeed, over the decades, that inspiration has gone both ways. However, more recently it seems like the adaptations have been influencing the comics to a greater degree than the comics have been influencing the adaptations, and in the long run that’s not good for either side.

* * *

Before we get too much further, let’s go back to Maggie Sawyer. Created by John Byrne as part of the post-Crisis on Infinite Earths Superman relaunch, she first appeared in April 1987's Superman Vol. 2, Issue 4. Often paired with Dan “Terrible” Turpin (a Golden Age character created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby as part of the Boy Commandos, and revisited as an adult in Kirby’s New Gods), Maggie was the commander of Metropolis’ Special Crimes Unit, which dealt with super-criminals. She was also the divorced mother of a young daughter, and her girlfriend Toby Raines worked for Metropolis’ other newspaper, the Daily Star. She quickly became a staple of the Superman titles, and starred in the 1998 spinoff miniseries Metropolis S.C.U. At some point between January 2001's Action Comics #773 and January 2002's Detective Comics #764, she transferred to the Gotham City Police Department, where she headed up the Major Crimes Unit. Consequently, she became a recurring character in the 2003-06 series Gotham Central, and met Kate Kane in November 2011's Batwoman #1.

Accordingly, while she’s spent most of the past twelve years in the Bat-office, it’s entirely possible that she could return to Metropolis -- say, if the character crops up in the Man of Steel sequel, and DC doesn’t want to confuse those elusive new readers by having her in a Bat-book. (Just ignore the fact that the movie will feature at least one other fairly prominent Bat-character.) While supporting characters have a little more flexibility in their personal lives, sometimes the pressure is almost as great to leave them inviolate.

Probably the quintessential supporting-cast change (and subsequent reversal) involved Alfred Pennyworth’s death, in June 1964's Detective #328. As it happens, this too was pretty early in a relaunch, specifically the “New Look” that had begun in the previous issue of ’Tec. It seemed like a good opportunity to break up Wayne Manor’s all-male atmosphere, so Alfred was replaced with Dick Grayson’s aunt Harriet Cooper. However, Alfred’s involvement in the Batman TV series prompted DC to revive the character in the comics, and after two and a half years he returned to duty in October 1966's Detective #356.

More recently, Suicide Squad boss Amanda Waller received a significant makeover for the New 52, which happened to follow her own appearances in other media. Created by John Ostrander and John Byrne, and debuting in November 1986's Legends #1, she also appeared in animated form (in Justice League Unlimited) and on Smallville, as well as on the big screen in Green Lantern. Those live-action adaptations weren’t as full-figured as the comics’ original, but neither were they as svelte as the current New 52 version.

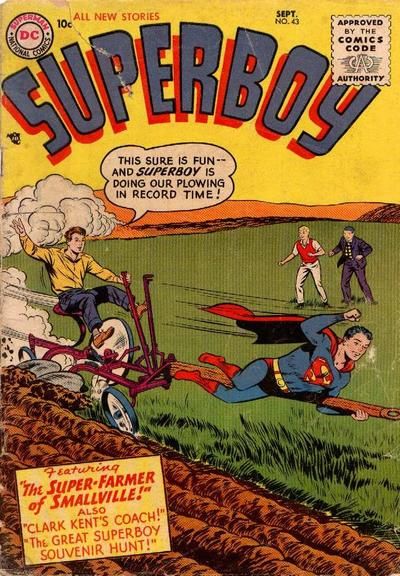

Now, Waller’s weight loss in the New 52 may just be coincidental, and not a result of her increased exposure -- but adaptations have influenced the comics for decades. Jimmy Olsen debuted on the Adventures of Superman radio show, so it’s only fitting that he was paired up with Smallville’s Chloe Sullivan when she finally made it to print. Speaking of body image, the 1940s Batman movie serials gave the comics a slimmer Alfred (as well as an early version of the Batcave). The aforementioned Superman relaunch of the mid-‘80s took many cues from the Christopher Reeve movies, and if you like Lois calling Clark “Smallville,” you can thank Dana Delany’s animated version.

There’s tons more, from Lynda Carter’s spinning costume changes to Super Friends eradicating Aquaman’s street cred; but you probably know ‘em all anyway. What I find interesting are the extracurricular examples that don’t affect the comics. DC seems content to let its corporate siblings dig deep into the back issues for all kinds of content, and fans are (understandably) happy when shows like Batman: The Brave and the Bold throw out such Easter eggs. However, B&B’s popular “Outrageous!” portrayal of Aquaman still hasn’t made a dent in his comics characterization.

To me this highlights the extent to which DC Comics has become less of a content farm and more of a content mine. Because (almost by definition) there are fewer DC movie and TV adaptations than there are comics, the former won’t run out of material from the latter for a very long time. While the direct-to-video animated features often adapt comics stories, DC’s most successful adaptations have drawn directly from the comics only on very rare occasions. The live-action Batman TV show did, of course (with DC collecting some of the original stories early next year), and so did the Batman, Superman and Justice League animated series, which each adapted a handful of comics stories. Batman: The Brave and the Bold even adapted a Batman manga.

However, none of the Reeve movies used specific plots from the comics, and neither did any of the seven modern Batman movies. Even Batman Begins’ homages to “Year One” and The Long Halloween were incorporated into a new plot. The same held true for television: Whether it was the 1970s’ Wonder Woman series, the 1980s’ Superboy, or the 1990s’ Lois & Clark, only the characters and the settings made it to the small screen. Indeed, while comics writers Howard Chaykin and John Francis Moore were story editors on the 1990-91 Flash series, it largely went its own way, and put its own spin on characters like Iris West, Captain Cold, the Mirror Master and the Trickster. Smallville eventually developed into the Archer-Daniels-Midland of content farming, adapting dozens of DC characters for television; but for the most part it left unseen their stories from the comics.

Therefore, we have two basic dynamics: a show like Batman: The Brave and the Bold, which traded heavily in Easter eggs and other familiar elements; and the first Christopher Reeve movie, which had little in common with most of the then-recent Superman comics, but which set the tone of Superman stories for decades to come. Even if we picture them as opposite points on a continuum, clearly these works had vastly different creative goals. With the kid-friendly B&B, the point much of the time was to celebrate everything goofily weird about DC’s superheroes; whereas 1978's Superman was a general-purpose blockbuster for an audience accustomed to disaster movies and Star Wars. No doubt DC hopes every adaptation will increase the audience for its comics, but over the years that seems to be less and less of a priority. The new head of Warner Bros. didn’t even mention the comics in his DC-movie cheerleading.

Accordingly, if the movies (and the video games, with which I am almost totally unfamiliar) start driving the content of the comics, that necessarily limits the comics’ creative options. More to the point, if DC Entertainment sees a strong correlation between the video-game audience (for example) and the comics audience, it may well impose a grittier, scarier, more “realistic” aesthetic not just on the comics characters featured in the games (like Harley Quinn) but across the board. After all, why alienate a crop of potential new readers with an array of storytelling styles, when you could just make everything look like Arkham City?

While I don’t think DC is quite there yet, line-wide impositions of tone like “Villains Month” show how easily the superhero line can be homogenized. Honestly, for the most part this has been a September to forget. I’ve liked about half of the villain spotlights so far, and I’m hoping the rest read better in the context of their respective ongoing storylines. A half-dozen books a week filled with horrible people doing horrible things to equally horrible people tends to have an effect, and it’s not one which makes me want more villain-heavy comics. Now I’m waiting for October -- gray, rainy, cold October -- to lighten the mood.

It’s doubly frustrating because DC is happy to share the lighter, wackier stuff with the kids’ line and with Cartoon Network. The Super Best Friends Forever! animated shorts probably reached 10 times as many people as the latest issues of Supergirl and Batgirl combined, and Warner Bros. wouldn’t be planning a Blu-ray release of Brave and the Bold if the show hadn’t been successful, but precious little of that spirit seems to have found its way back to the comics themselves. Therefore, I have to ask: What does DC think the fanboys of 2033 will find nostalgic? What will spark their imaginations, and encourage them to revisit the comics of the New 52?

To be fair, it may be something like Batman, The Flash, Batwoman or Wonder Woman, each of which is a fairly well-done series from a stable creative team. However, as the stable creative teams disappear, so do the well-done series; and if editorial demands that everything look and sound the same anyway, the distinctiveness that facilitates nostalgia disappears as well.

Look, I know there were a lot of clunkers in the Golden Age, the Silver Age, the Bronze Age and whatever Age you call this one. Regardless, there were enough memorable moments to inspire future pros and readers to give DC’s superhero line a chance. That kind of invention is what comics does best. I bet you don’t see a robot dinosaur in Ben Affleck’s Batcave, a golden key pointing the way to Henry Cavill’s Fortress of Solitude, or a Flash costume popping out of Grant Gustin’s ring. The adaptations can never be as inventive as the comics -- and when the comics start limiting themselves to what the adaptations deem acceptable, the content farm stops growing.*

So let Maggie Sawyer marry Kate Kane. Let Amanda Waller have an extra sandwich. Let the comics draw inspiration from the adaptations -- but let the comics do what they want.** The radio gave us Jimmy Olsen, but the comics made him a legend. Now the comics are taking old TV adaptations in new directions, greatly expanding the worlds of ‘60s Batman, Smallville Superman, and Batman Beyond. (I hesitate to call that the “recycling” component of the content farm.)

Those comics are doing what the shows couldn’t, because comics can do anything -- from cosmic restructuring to promoting a diverse array of characters. Recognizing that limitless potential, and giving creative teams the freedom to act on that potential, are the foundations of a truly sustainable content farm. Otherwise, DC will become merely a warehouse of aging, musty ideas, propped up by the narrow tastes of a dying demographic.

+++++++++

* [I have already argued that the rate of growth has slowed.]

** [This doesn’t mean letting Alfred stay dead. Even without the TV show, someone would have brought him back sooner or later.]