Last week I asked why the Silver Age is so pervasive in DC lore. Even though that’s something of a rhetorical question, I felt like it was left largely unanswered. The short answer is that the Silver Age represents the modern DC Universe’s origin story, so you’re never going to get rid of it entirely, regardless of reboots, relaunches, and/or legacy characters. However, in terms of style and tone, things are naturally more complicated.

It’s hard for me to talk about the Silver Age without relating it to the subsequent Bronze Age, mostly because I grew up with the comics of the mid-1970s. I see the Silver Age as an era of wild ideas, told in standalone stories which were light on consequences, whereas the Bronze took those stories and ideas and extrapolated a more “realistic” status quo from them. This is not to say that the Bronze Age was some vast improvement, since realism in superhero comics is a tricky prospect at best.

However, to me that point of compartmentalization, at which a previous creative team’s run goes from an ongoing concern to a finished body of work, is highly significant. That’s when the rules governing a feature are established (or amended), and therefore that’s when the people in charge of that feature decide how (and how much) it can grow. The same applies in the aggregate to the universe those features share.

* * *

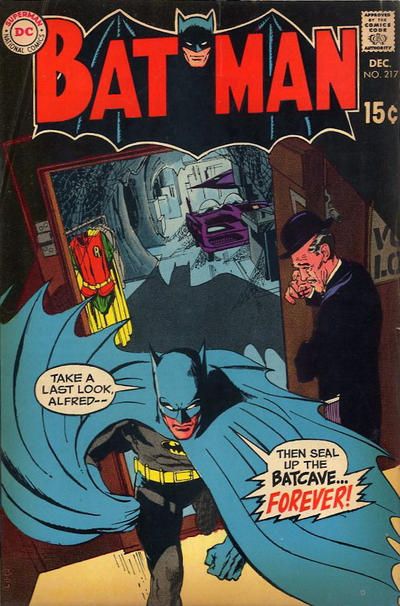

For the sake of discussion, let’s say the Silver Age started in 1956 with its version of the Flash, and ended in 1969, following such developments as the Doom Patrol’s deaths (1968) and a Robin-less Batman’s move out of Wayne Manor (Batman #217). We might also make a strong case for the end coming with Green Lantern #75 (March 1970), the last issue before Neal Adams joined Denny O’Neil for the landmark #76.

This lets us classify the Silver Age generally in terms of the aforementioned wild, standalone, consequence-free stories. Any changes or continuing subplots were short-lived and/or insignificant: Alfred’s “death,” Hal Jordan’s job-hopping, weddings in Flash and Doom Patrol, etc. By contrast, the characters “grew up” (sometimes literally) during the Bronze Age. The other Teen Titans graduated from high school, if not their original codenames. Clark Kent moved to broadcast journalism. Barry Allen grew out his crewcut, and both he and Jimmy Olsen gave up their bowties. And, of course, Green Lantern and Green Arrow questioned the very purpose of their superhero careers as they journeyed across America.

Here’s where it starts to get tricky. In a practical sense, you don’t get to the Bronze Age without going through the Silver. The great Green Arrow soliloquy from GL #76, which basically asks “what are we doing chasing bad guys when the real world is falling apart around us,” loses much of its impact if the reader isn’t at least aware that these guys have had long, colorful, and (allegedly) frivolous adventures. The specifics of those adventures are less relevant than their mere existence, because cumulatively those stories have established a certain familiar style -- if not an outright formula -- which in the Bronze Age can then be manipulated. It’s enough to note that the Flash was once turned into a puppet, or had a giant head, because those can serve later as nostalgic and/or ironic callbacks.

Accordingly, back in the day, I wasn’t overly invested in the specifics of the Silver Age. (Note: I didn’t read much of the Legion of Super-Heroes, which might have made a difference.) For a while Justice League of America had a two-page feature called “100 Issues Ago,” which was just what it sounds like. Along with the tabloid-sized reprints, it was my introduction to the Gardner Fox/Mike Sekowsky days, and I have to say, those stories seemed kind of weird to my grade-school eyes. In JLA #44 (May 1966), a villain called the Unimaginable (who had been trying to join the League, and was spurned) caused a handful of Leaguers to double in size, with further tragedy surely to follow. I don’t remember the exact plot, but the picture of an oversized Batman and Green Lantern freaked-out in tattered uniforms remains striking, and a little disturbing. Likewise, “Deadly Dreams Of Doctor Destiny!” (JLA #34, March 1965) features Wonder Woman forced to fight crime under an expressionless porcelain mask (alongside teammates saddled with similarly-debilitating gear); and while its plot has stuck with me more, the images are indelible. Maybe it was just Sekowsky -- who, incidentally, drew Hawkman’s mask with these huge, dead, ever-staring eyes -- but it was a far cry from the more naturalistic style of his successor Dick Dillin, who pencilled JLA from the late ‘60s until his death in 1980.

So to me the Silver Age was just different. Other creative changes, especially on the artistic side, reinforced these differences. Carmine Infantino was long gone, and Irv Novick was the regular penciller, by the time I started reading The Flash; and Mike Grell had a lot more in common with Neal Adams than with Gil Kane on Green Lantern. Although the difference isn’t really style over substance, the Silver Age’s distinctive style appears to be more enduring than its specifics. To a degree this is understandable, if one’s goal is to make sense of DC’s output during the period. We think of the Silver Age -- not unreasonably -- as dominated by Infantino, Fox, Sekowsky, Kane, Julius Schwartz, and John Broome. However, the Mort Weisinger-edited Superman titles were also going strong, as were (for a few years, at least) Jack Schiff’s Batman line, still in its sci-fi period. Trying to harmonize all those disparate influences, let alone shape them into a cohesive, functional shared universe, is more of an aspiration than a plan. (Not that there aren’t some impressive timelines out there.)

Naturally, not every Silver Age story could survive the transition into Bronze Age realism, so DC’s fictional history tends to get lost in misty watercolored memories the farther back you go. There’s no DC equivalent of Fantastic Four #1 to mark clearly where everything kicked off, leaving us only with discrete scenes -- an exploding planet, a botched robbery, a queen’s answered prayer -- to stitch together into an impression of the DCU’s early days. Compare the treatment of the Golden Age stories in the context of Earth-2, where the original Action Comics #1, Detective Comics #27, etc., could be inserted with minimal fuss into that universe’s timeline. Such fidelity makes that Earth separate and distinct enough that today, we can take it or leave it, like a box of old photos stored in the attic.

However -- and here I will indulge in yet another erudite metaphor -- the Silver Age has long since left its narrative form behind, transcending it to become a state of mind. Talking about Identity Crisis and his Justice League stint, Brad Meltzer said that

One of the clear goals of Identity Crisis was to pull all those Silver Age stories back into continuity, and to acknowledge the glorious past. That doesn’t mean every story has to come in with the (way overused term) “grim and gritty.” But we also shouldn’t let them all be brushed aside either.

In fact, Identity Crisis centered largely around a JLA three-parter from the Bronze Age late-‘70s (#s 166-68, May-July 1979), and featured a beloved supporting character introduced during the Silver Age, and murdered by another Silver Age stalwart. Without getting deeper into a Meltzer/IC critique, it’s enough to note that reinforcing the canonical nature of those old stories is, on one level, “acknowledging the glorious past.” Yes, Jimmy Olsen was turned into all manner of creatures; yes, there was a Bat-Hound. In that sense, the Silver Age was a clear influence on DC’s superhero line for some fifty-five years. I’m not sure how much of those references will crop up in the New 52, but I doubt they will ever go away completely.

Regardless, Identity Crisis was not a Silver Age story. Neither was “Snapper” Carr’s return as a reluctant villain in JLA vol. 1 #s 149-50 (December 1977-January 1978), nor the brief reintroduction of Guy Gardner (soon to fall into a coma) in mid-‘70s issues of Green Lantern, nor the search for the Doom Patrol’s killers in New Teen Titans #s 13-15. We may want to reclaim the anything-goes spirit of the Silver Age -- and in the ‘90s, Gerard Jones, Pat Broderick, and Mark Bright’s Green Lantern, Mark Waid and company’s Flash, and Grant Morrison and Howard Porter’s JLA came very close -- but it takes more than a fondness for Easter eggs and an earnest devotion to continuity.

As someone who discovered DC’s superheroes well into their new-for-the-‘70s forms, I remain eager to see what they were like before all that. Certainly DC is happy to sell all manner of reprints to fans like me, and just this week I got an unexpected thrill re-reading the first comic-book pairing of Superman and Batman in World’s Finest Archives vol. 1. I’ll always appreciate Easter eggs and continuity references, although I understand how they might alienate new readers.

Still, if a new reader can get past that alienation, or can find a story which avoids the issue entirely, a shared universe with a rich history can be a fertile field of exploration. This is part of why I’ve been glad to see the “Retro-Active” specials and the Games graphic novel, and part of why I lobbied for a classically-minded Challengers of the Unknown revival last week. Getting in on the ground floor is exciting enough, but getting into something so big it’ll constantly seem new can be even more rewarding. The fact that the Silver Age has become this idealized state of mind, and not just a collection of wacky stories, only adds to its appeal.

That’s why, regardless of its relevance to the New 52, I think the Silver Age will endure. Not only was it too important to DC’s superhero line for too long, it has morphed into a general spirit of optimistic experimentation which, these days, can be a nice contrast. If current sales are any indication, DC can get along pretty well without those old references and retro-style plots -- but I think that sooner or later, it will choose not to.