In the long run, DC Comics canceling Teen Titans may not mean much: The Legion of Super-Heroes is on hiatus, but it'll be back. Likewise, I think there will be a new Teen Titans title -- maybe called Young Justice? -- sooner rather than later.

What’s curious about the end of this particular series, which coincides with writer Scott Lobdell's departure, is it suggests more than just a name change. The Titans began as an all-star team, like their mentors in the Justice League, but over time the title focused increasingly on interpersonal relationships. The New 52 version of the team now features a Wonder Girl and Kid Flash who have virtually no connection to their older namesakes. Only Superboy has a solo title, and besides him only Red Robin appears regularly outside of Teen Titans. That makes the Titans rather insular, so I wonder if the inevitable relaunch will try to address that.

Whatever happens, odds are that the all-star structure that characterized DC super-teams since the 1940s has faded into the background for good. This week we’ll examine the Titans’ place in the superhero line, and see what the book has to offer going forward.

* * *

The Teen Titans’ history dates back to June-July 1964's The Brave and the Bold #54, which featured a prototypical lineup of Kid Flash, Aqualad and Robin. A year later, the “real” team (now including Wonder Girl) debuted in June-July 1965's B&B #60, and got another one-off spotlight in Showcase #59 (November-December 1965) before headlining its own series. Teen Titans Vol. 1 started in January-February 1966 and lasted just over seven years, ending with January-February 1973's Issue 43. It was revived briefly in 1976, picking up the old numbering (gasp!) and getting a slight upgrade to eight-times-a-year status, but it ended with a heretofore-unknown origin story -- one that, unlike B&B #54, included Speedy and Wonder Girl -- in February 1978's Issue 53. Just under three years after that, a preview in October 1980's DC Comics Presents #26 kicked off the New Teen Titans, which ran in various forms and under various titles for 16 years. Different takes followed, including Dan Jurgens’ all-new Teen Titans Vol. 2 (1996-98), Peter David and Todd Nauck’s Young Justice (1998-2003) and Teen Titans Vol. 3 (2003-11), which started off under writer Geoff Johns and artist Mike McKone. All these series have kept the Titans on DC’s schedule for most of the past 33 years.

However, in a sense the Titans have been playing catch-up virtually from the beginning. Teen Titans had the misfortune to debut at the height of the Marvel Age of Comics, when Stan Lee and Steve Ditko were mining deep veins of teen angst in The Amazing Spider-Man, and Lee and Jack Kirby were well into their every-issue-a-landmark Fantastic Four. In fact, B&B #60 most likely shared shelf space with July 1965's X-Men #12 (by Lee and Kirby, natch), featuring “The Origin of Professor X!” and the first appearance of the Juggernaut. The Justice League might have compelled Marvel to create its own super-team, but the Titans were two years behind their cross-town peers.

Moreover, according to Gerard Jones and Will Jacobs’ The Comic Book Heroes, Titans writer Bob Haney turned out “pop-culture references and cute slang that could have seemed convincing only to kids too young to know better” (revised 1997 edition, Page 77). The first few years of Titans have widely been seen as painfully un-hip examples of aging, out-of-touch writers trying to replicate a youth culture about which they apparently knew little. That started to change around Issue 18 (November-December 1968), when younger writers like Len Wein and Marv Wolfman, Mike Friedrich, Steve Skeates and writer/penciler Neal Adams succeeded Haney. In Issue 25 (written by veteran Bob Kanigher), the book underwent a radical format change, as most of the Titans gave up their costumed identities to work for a new patron, Mr. Jupiter. This didn’t last too long -- for a while, the Titans decided to put on the costumes for more traditional adventures, but otherwise work “plainclothes” for Mr. Jupiter -- and by the time the book was canceled, the group was back to being full-time superheroes.

All of this highlighted a series that struggled against its basic structure. Certainly the Titans’ initial appeal was as a junior Justice League; but their demographics dictated that they needed to be more ... fun, for lack of a better word. It was probably enough for the JLA to keep to the same basic formula -- supervillains, aliens, visiting Earth-Two -- but the Titans needed to be convincing both as superheroes and as teenagers. The “Mr. Jupiter” stories got the group even further from its all-star roots by bringing in Lilith Clay and Mal Duncan, two new Titans who were weren't sidekicks, superheroes or even preexisting characters. While the book still focused on Kid Flash, Wonder Girl, Speedy, and Hawk and Dove, Lilith and Mal set precedents for Titans-specific characters to come.

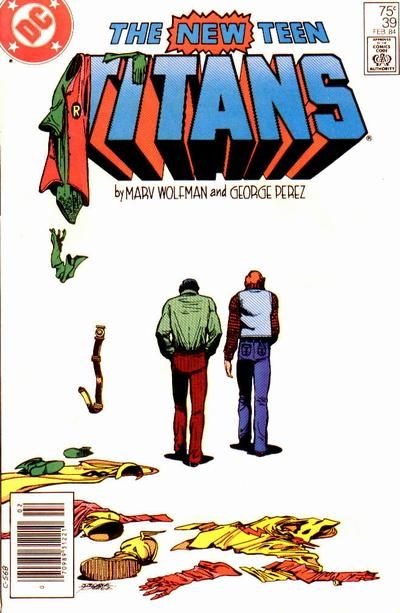

Accordingly, New Teen Titans featured a mix of old and new characters, with rookies Raven, Starfire and Cyborg joining Robin, Wonder Girl, Kid Flash and Beast Boy/Changeling. Raven recruited the new team (when she couldn’t get the Justice League), Cyborg’s father provided their Titans Tower headquarters, and their first official mission was to rescue Starfire from her slave-ship captors. Of the original Titans group, only Robin, Aqualad and Kid Flash had appeared regularly outside of the Titans series (i.e., in the Bat-books, Aquaman and Flash), and the same was even more true for New Teen Titans. In fact, Wolfman was also writing Robin in Batman when NTT launched. All that meant NTT was well-suited to examine its characters without worrying about contradicting other creative teams. Of course, this was diametrically opposed to JLA, whose roster was full of solo stars.

Indeed, at the height of NTT’s popularity, JLA writer Gerry Conway re-focused that series on characters like Aquaman, Elongated Man, Zatanna and Martian Manhunter, who didn’t have to worry about “outside commitments” like their own books. Of course, they became the core of the Detroit League, which was rounded out with characters that, with the exception of Vixen, were created specifically for JLA. That didn’t work out so well for the title, and the next big format shift (Justice League International) featured characters with their own series (Batman, Blue Beetle, Guy Gardner, Captain Atom, Booster Gold) -- but soon enough, JLI’s cast included characters like Fire and Ice (and Beetle and Booster, whose books had been canceled), who appeared nowhere else. Meanwhile, throughout its roster changes, New Titans remained rather insular -- except for a brief period in the mid-‘90s when it featured Supergirl, Impulse and Green Lantern Kyle Rayner -- and the new characters starring in Jurgens’ Teen Titans Vol. 2 continued the trend.

It took the success of Grant Morrison and Howard Porter’s big-name JLA to usher in a new round of all-star teams. By the beginning of 1999, there were three more such books. JSA included Birds of Prey’s Black Canary and Wonder Woman’s Hippolyta, as well as Starman’s Jack Knight. Young Justice’s Robin, Superboy and Impulse each had his own series, and the new Wonder Girl came over from Wonder Woman. Finally, the adjective-free Titans series was basically a New Teen Titans update, but by that time Nightwing and the Flash had their own titles.

* * *

I've spent a lot of space talking about the Titans as an all-star group, and I think that’s an important factor in its development. However, also important is the extent to which the various Titans series used not just preexisting characters, but characters that had fallen off the radar even in their home titles. Originally this meant focusing on Kid Flash, Wonder Girl, Aqualad and Speedy, because they weren’t getting enough attention elsewhere. Over time, however, this became self-fulfilling, because those characters tended not to appear anywhere else. The approach produced dividends. Robin became Nightwing so that Dick Grayson could be a full-time Titan and Batman could have a full-time sidekick; and after Superboy’s series was canceled, Johns and company revised his origin and emphasized how close he was to his teammates. Indeed, DC’s second generation of sidekicks -- Tim Drake, Kon-El, Cassie Sandsmark, Bart Allen, et al. -- started pushing the original group of Titans to the background in the late ‘90s, and Dick’s generation is now scarce in the New 52.

However, the New 52 relaunch also did a funny thing to the Teen Titans: It kept a core of “all-star” names, but by and large separated those characters from their traditional mentors. It’s as if DC decided it needed a series called Teen Titans starring a certain collection of characters, but without the legacy structure that originally created and nurtured those characters. Therefore, the question now becomes whether that structure is still relevant to Teen Titans, or whether it can just be a book about Tim, Kon, Cassie and Bart.

The latter seems more likely, as I doubt DC is going to recreate that structure any time soon. As Caleb pointed out, the New 52 has accumulated a surprisingly deep bench of teenage (or youngish) superheroes in lest than two and a half years. Some, like Amethyst, Stargirl, Supergirl and Batgirl, are already affiliated with super-teams, but characters like Static, Blue Beetle III and Batman Incorporated’s Raven Red -- not to mention the Ravagers, which included some familiar Titans types -- would fit well on a Titans team. At the risk of SPOILING a low-selling title, the final issue of The Green Team (speaking of characters needing a post-cancellation home) even suggests they could finance the Titans.

Still, what purpose would the new Titans serve, beyond being a collection of familiar characters? As mentioned above, this isn't a new concern. In the Silver Age, the Titans fought crime just because: They did it with their adult mentors and their adult mentors did it as part of the Justice League, so their own group was the next logical step. Starting with the New Teen Titans, though, that rationale got a little more fuzzy. Recruited to defeat Raven’s demonic father, they just sort of hung around together until they became (in the words of no less than George Pérez) “a group of characters sitting around a table waiting for a safe to fall on them.” In any event, the new Titans should distinguish itself from the New 52's current teens-with-a-purpose title. The Movement may not sell like a Titans book, but it has a definite viewpoint and tries admirably to fill the insurgent-youth role Titans originally courted.

Of course, Titans can always use at least the appearance of an all-star lineup to stand out, even if it ends up being the superhero equivalent of the cool kids’ table. Part of me thinks the series will recruit some of the preexisting characters mentioned above, if only to justify its relaunch.

A fresh take on Titans can only help the New 52, which at the moment seems a little short on super-teams. Besides the three Justice League series (and “out-of-town” titles Earth 2 and JL 3000), only Birds of Prey, The Movement and Aquaman and the Others are set to survive April. In terms of numbers, that’s not so bad -- the New 52 started with nine team titles, and right now May will have at least eight -- but three versions of the Justice League and three more eclectic ensembles make this collection somewhat top-heavy.

Along those lines, Titans could serve as a bridge between the Leagues and the more small-scale groups. Whatever the details, the Teen Titans have always been heirs apparent to the Leaguers. (The last pre-New 52 iteration of the JLA made this plain, with a number of ex-Titans in the lineup.) Time to refocus on that, and perhaps contrast the cool kids like Superboy and Wonder Girl with some lesser-knowns who are just as deserving. Given time and the right creative team, Teen Titans could combine the Justice League’s all-star appeal with the vivid characterization to which the series has always aspired. That would help Teen Titans live up to its potential, and it might make for some good comics as well.