I really like Halloween, but it’s always been hard for me to come up with a spooky post that relates to DC Comics. The emphasis here is on “for me”: DC has a wealth of spooky material from which to draw, and I’ve just never been able to work with it meaningfully.

For this year’s Halloween post I thought about doing a survey of DC’s horror-themed titles over the years, because certainly the publisher has had its share. There are stalwarts that go back decades, like House of Mystery, Swamp Thing and The Sandman (whose sequel miniseries starts this week, as you might have heard). The first round of New 52 titles included I, Vampire and Frankenstein, Agent of SHADE -- and while both of those have bitten the dust, Justice League Dark still heads up the superhero line’s magic-oriented section.

However, the more I thought about it, this space is really not big enough -- yes, even with my extreme verbosity -- to do right by the horror books. Besides, most of them have ended up at Vertigo, although some are being reincorporated into the superhero line. House of Mystery is a good example of the “serious horror” migration. It started out in the ‘50s as a supernatural anthology before switching over to science fiction (after the fall of EC) and then, briefly, superheroes (specifically, the Martian Manhunter and “Dial ‘H’ for Hero”). When the Comics Code relaxed its stance on all things scary, HOM told horror stories, including an extended run as the original home of “I, Vampire.” The title ended in 1983, after 32 years and more than 300 issues, but it’s never really been forgotten. The House itself (along with its companion from another eponymous title, the House of Secrets) became a part of The Sandman’s landscape, and was the setting for a Vertigo relaunch, which ran from 2008 to 2011 (42 issues and a couple of specials). Now it belongs to John Constantine and serves as Justice League Dark’s headquarters, which I suppose is better than limbo.

We could chart similar courses for more DC-centric books, most famously Swamp Thing, The Sandman and Hellblazer, each of which started out as part of the main superhero line, with clear connections to the larger DC Universe. Swampy teamed up with Batman and Superman in Brave and the Bold and DC Comics Presents, respectively. (The House of Mystery also appeared in both books.) In his early mid-‘80s appearances, Constantine was a friend of the Doom Patrol’s Steve “Mento” Dayton, which in turn linked him to Dayton’s adopted son Gar “Beast Boy/Changeling” Logan, then a member of the New Teen Titans. Dream/Morpheus didn’t guest-star in any other DC books, but his sister Death appeared to Captain Atom as the latter made his way through the afterlife.

The separation between the superheroes and Vertigo characters -- which lasted almost 20 years, from the early 1990s until Brightest Day reintroduced Swamp Thing and Constantine in spring 2011-- also seems to have given Vertigo preference for those kinds of horror- and supernatural-themed series. Put another way, if you map out the different genres represented by DC characters, from “pulp adventure” (Batman, Green Arrow) to “sci-fi” (Green Lantern, Adam Strange) to “mythology” (Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel), etc., characters could travel freely from one area to another, but the “horror” area would be set apart.

Now, one might say this didn’t really hurt either side, and probably helped Vertigo find and build its audience. The superheroes could still fight vampires and other monsters, the new Dream showed up in JLA and Death chatted with Lex Luthor, and generally there were plenty of genres to explore apart from those represented by the ex-DCU folks. Likewise, Vertigo’s ex-DCU series were free to ignore the constraints of superhero continuity (including the flexible timeline) and perceived content restrictions.*

Still, because those characters provided easy access to their particular genres, I was never a fan of the wall between DC proper and Vertigo. Horror is a powerful narrative form, and a character designed to explore horror tropes can occupy a very special place in a shared universe. It’s relatively easy for the superheroes to step outside their home genres -- for Batman to fight aliens on distant planets, or for Wonder Woman to bust up an organized-crime ring -- but the wild cards which come with Secrets Man Was Not Meant To Know may make them call in Constantine or the Phantom Stranger. Even superheroes can become mere tourists in realms largely uncharted, so the spotlight can then shift to the horror-centric characters.

Nowadays, reintegrating those characters into the larger superhero line also means rethinking the aforementioned genre map. Instead of putting “horror” in a corner or off to the side, it may well lie under all the other genres. I might have been the only person not named Scott Snyder or Jeff Lemire who liked “Rotworld,” but I enjoyed it mainly because it showed how easily the superheroes could be caught off-guard by fundamental forces about which they knew nothing. I also appreciated how it established Swamp Thing and Animal Man as important guardians of the cosmic balance. Similarly, when I, Vampire hinted that Mary’s army might wreak havoc across DC-Earth, I enjoyed seeing Batman, Constantine and JL Dark doing their part to stop it.

The sense that our mundane lives could be ripped apart instantaneously by distant, implacable elements facilitates some very creepy feelings. Horror plays on our anxieties, whether they’re about various forms of apocalypse, the fear of The Other, or struggles with our own dark impulses. We want to be reassured that we can manage these fears, so we scare ourselves under specific circumstances, safe in the knowledge that what we’re reading or watching is (probably) not real. Besides, we’re guided and protected by Morpheus, Zatanna, the Spectre, or whomever, so it’s all going to be OK ...

... Except that a lot of horror stories don’t end on “OK.” If they’re not outright tragedies, then the killer’s still on the loose, or the monster’s only been contained, or the last image is of the antagonist’s unsettled mind. Horror exists in no small part to remind us that (even if it’s only a story) bad things happen and bad people are out there, so beware the hanging plot thread.

In a sense, horror shares this trait with open-ended storytelling, which also wants to keep its readers anxious so they’ll keep coming back. Of course, this isn’t the only way to keep readers coming back -- endearing continuing characters are often their own reward -- but that sense of constant peril is pretty reliable. Surely something similar has motivated September’s “Villains Month” and the Forever Evil event, which use their bad-guy spotlights to play with both the audience’s perceived desire to be scared and its curiosity about what happens next. I read most of the villain spotlights because I figured they set up motivations and plot points which would be important to future superhero storylines, and not because I wanted a few dozen issues’ worth of constant nihilistic carnage. I don’t mind reading about bad people doing bad things, but I do want a sense that such things won’t be rewarded, and will in fact be punished.

Naturally, that last part is also a recurring motif in horror fiction, whether it’s an ironic EC-style comeuppance or a slasher film’s “sex = death” formula. Horror’s approach to morality is a topic a little too big to be discussed fully here, but it’s enough to say that it’s not exactly the same as the superheroes’ more conventional good-beats-evil outcome. Indeed, while the morality of superhero stories has its own complexities, the very idea of a superhero is a way to stack the deck in favor of “good.”

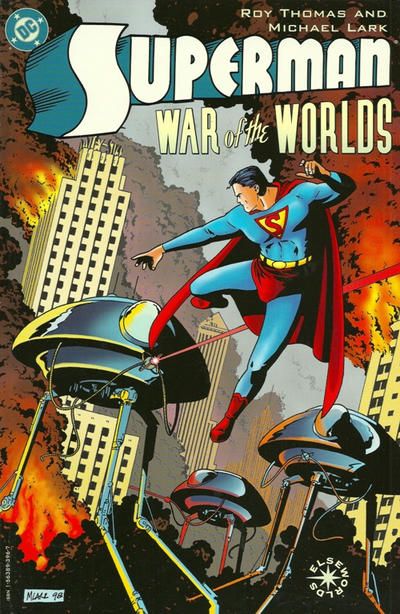

Take H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, wherein humans fight an increasingly desperate series of skirmishes against gigantic, invulnerable Martian tripods. That story goes the other way, shifting the balance of power towards “evil” (or at least “not good”), but writer Roy Thomas and artist Michael Lark decided to even things up in the 1998 Elseworlds one-shot Superman: War of the Worlds.** Needless to say, the Man of Steel (the 1938 version, appropriate to Orson Welles’ contemporaneous WOTW adaptation) defeats the invaders. For that matter, nine years earlier Mark Waid, Brian Augustyn and Mike Mignola had set a Victorian-era Batman against Jack the Ripper in Gotham By Gaslight. On one level these are just substitutions -- the tripods for a mad scientist’s mechanical monsters, the Ripper for an Arkham escapee -- but I believe they represent a need to assert control over what we saw was unstoppable and/or unpredictable. Superheroes are supposed to have happy endings.

If that sounds simplistic, or even childish, it comes with the territory. Besides, we always have those complexities I mentioned a couple of paragraphs ago. I suspect we’ve all read enough superhero comics to come up with our own lists of “net good” outcomes, where even with some gray areas an ending was still in positive territory. A positive (if not outright happy) ending rewards the reader for sticking with the story through its emotional peaks and valleys. A positive ending also allows the reader to pause and take a breath before the next round of calamities start.

That’s a big part of what made “Villains Month” so much of a frustrating slog. For me, it was four weeks’ worth of macabre plot points and character beats -- a steady barrage of negative energy, endured in the hope that collectively, it would make the overall stories more rewarding. As such, there weren’t a lot of immediate emotional payoffs, so the cumulative effect was even more draining. I realize this is largely from the perspective of an every-Wednesday reader, so digesting the “Villains Month” stories as part of their individual series’ collections several months down the road will probably be a different experience. Nevertheless, if I’m going to stay part of the Wednesday crowd, I’ll need positive reinforcement more frequently.

I’m not prepared to say the darkening of DC’s superhero line is connected directly to the wall between the DCU and Vertigo, but I wonder if it didn’t close off an avenue of storytelling the superhero line had previously enjoyed. Neil Gaiman (timely!) wrote Green Lantern/Superman: Legend of the Green Flame around the time The Sandman was just getting off the ground, originally as a special issue of Action Comics Weekly. GL was Action’s headliner (in lieu of his own title) and Superman had been shifted to a two-page Sunday-style strip, so that each oversized issue could showcase rotating features like the Demon, Blackhawk or Deadman. The story’s central sequence featured Superman and Green Lantern in Hell, with Hal Jordan trying to get his mojo back and Supes paralyzed by not being able to tune out the anguished cries of countless tormented souls. As you can imagine, it was pretty intense. It didn’t really depend on the superheroes meeting Morpheus, Lucifer, or any other future-Vertigo character; but it’s the kind of story which might not have happened after the Vertigo migration. Without a dedicated horror outlet -- without easy access to someone like Morpheus, Death, or Lucifer -- the superhero line had to either use demon-lords like Neron or Satanus, or go in more down-to-earth directions.

Of course, there’s always the notion that you don’t want Batman or Green Arrow necessarily going to Hell (although Kevin Smith brought Ollie Queen back from Heaven) when their home genre is noirish enough. When you get down to it, dark is dark, whether it’s that new Joker’s Daughter or something more eldritch. However, to me it seems more acceptable to say “the devil made them do it” in a superhero story, because it takes the story out of the regular superhero stylebook, and brings in an element with which most superheroes are unfamiliar. In so doing, it insulates the superhero line generally from dark, spooky tales, because it implies that these aren’t supposed to happen all the time.

Lately, DC has been justifying its villain spotlights as benchmarks to gauge its heroes’ presumed superiority. For a while now refrain has been that “heroes are only as good as their villains,” or something similar. Under this mindset, the superhero titles have showed those villains engaged in all manner of grotesque deeds. Maybe the Vertigo wall contributed to this; maybe it didn’t. Maybe this post itself has been an exercise in using horror and the supernatural to manage my own anxieties about DC’s superhero line. After all, that’s a big part of Halloween’s appeal.

Regardless, I don’t think DC can sustain an extended focus on the bad guys -- and since the superhero line has been cultivating horror-flavored titles, I’m hoping that the more conventional books can lighten up a little. Otherwise, it might start to feel like Halloween every day.

++++++++++++++++++++++

* [For what it’s worth, I have heard James Robinson’s Starman described as a “Vertigo-style” superhero book, and I always thought Matt Wagner and Amy Reeder’s Madame Xanadu, with its playful approach to superhero continuity, would have fit well in the main superhero line.]

** [Both Superman and Orson Welles’ WOTW radio adaptation debuted in 1938, the former in April and the latter on October 30. A while later, Welles appeared in January-February 1950's Superman vol. 1 #62, teaming up with the Man of Steel to foil a real Martian invasion.]