Remember when Batman was a jerk?

Remember when Batman was such a jerk that no less than Mark Waid called him “broken”?

Starting in 2006, writer Grant Morrison aimed to help fix him; and this week, with Batman Incorporated Vol. 2 #13, Morrison concluded his Bat-saga. The issue is a neat encapsulation of the themes Morrison has played with for the past seven-plus years -- including the portability (and immortality) of “Batman,” the uniqueness of Bruce Wayne, and the importance of not going alone -- all drawn with verve and giddy energy by Chris Burnham. (There’s even a dialogue sequence where the punchline is “Cancelled!”) Like the infinite-Batman cover or the eternal-circle image that dominates an early spread, Batman will go on, but it is the end of a unique era.

As usual, though, some history first ...

* * *

By 2005, whether he liked it or not, the Darknight Detective had garnered a decent-sized set of costumed associates. While each had his or her own motivation, and each added a particular flavor to the Bat-books, they all shared the same basic trait of Not Being Batman. Similarly, each tended to enjoy the same treatment from Batman: a certain level of acceptance, building to an inevitable clash that was some variation on Only Batman Can Do This.

This template was not entirely new. From 1989's freakout following Jason Todd’s death, to 1992's “Knightfall,” 2000's “Tower of Babel” and “Divided We Fall” (both in the Waid-written JLA), 2002's “Bruce Wayne: Fugitive” and 2004's “War Games,” various storylines illustrated the bad effects of Batman’s unilateral actions. (1999's “No Man’s Land” was contrapositive, showing Batman carefully planning an effective way to protect quake-ravaged Gotham.)

However, by 2005 things had gotten pretty dark throughout DC’s superhero line. In the Bat-arc “War Games,” Stephanie “Spoiler/Robin IV” Brown had died after being tortured by Black Mask, Identity Crisis had killed off Sue Dibny and Tim Drake’s dad (among others), and the run-up to Infinite Crisis included Blue Beetle’s murder and the revelation of Batman’s Brother Eye spy satellite.

With all that as backdrop, blogger Alan Kistler asked Mark Waid “is there any fear that we’re going back to the grim and gritty 80s?”

The good news is, and I guarantee you this, when we’re on the other side of [Infinite Crisis], those days are GONE. Just gone. We’re sick to death of heroes who are not heroes, we’re sick to death of darkness. Not that there’s no room, not that Batman should act like Adam West, but that won’t be the overall feeling. After all this stuff, after everything shakes down, we’re done with heroes being dicks. No more “we screwed each other and now we must pay the consequences.” No, we’re super-heroes and that’s what we do. Batman’s broken. Through no ONE person’s fault, but he’s a dick now. And we’ve been told we can fix that.

The “we” in question were probably the writers of 52; namely Waid, Greg Rucka, Geoff Johns, and Grant Morrison. Specifically, at a WonderCon panel on Feb. 11, 2006, Morrison revealed he would be the next Batman writer,* promising that “[t]he Batman coming off of 52 is a very different guy. He's a lot more fun to write, a lot more healthy. If you remember the Neal Adams, hairy-chest, love-god Batman, he's more like that guy.”

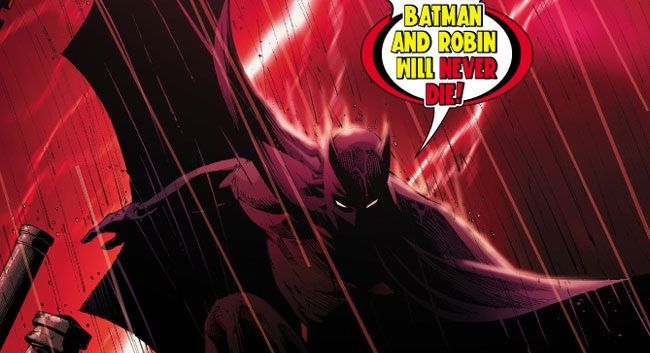

Somewhat ironically, then, Morrison’s run may be remembered best not only for the declaration that “Batman and Robin will never die,” but also for the deaths of both Batman and Robin. Of course, it turned out that Bruce Wayne didn’t actually die in “Batman R.I.P,” but in the Morrison-written Final Crisis; and that turned out to be a ruse as well, because Darkseid just sent Bruce back into Earth’s prehistoric past, turning him into a sort of “time bomb” that would explode when Bruce actually clawed his way back to his own time. By comparison, Robin’s death was practically an afterthought: impaled during a fight with his own artificially aged clone.

But that’s getting off the track. Morrison had worked on Batman before, most notably in 1989's Arkham Asylum graphic novel (with artist Dave McKean), 1990's Legends of the Dark Knight arc “Gothic” (with artist Klaus Janson) and in JLA (1996-2000; various artists). In JLA, Morrison introduced three variations on Batman: the villain Prometheus, who as a child watched his criminal parents shot by police; the Batman of the 853rd century; and the evil parallel-Earth counterpart Owlman. However, the current set of stories -- which started in the main Batman title before migrating to Batman and Robin, the Return of Bruce Wayne miniseries, and eventually Batman Incorporated -- examined the relationship between Bruce and Batman, and particularly the extent to which anyone else could “be” Batman.

Indeed, Morrison established a new trio of “replacement Batmen” right from the start of his first issue (Batman #655), and alluded to Bruce’s own “replacement personality” with graffiti representing the Batman of the alien world Zur-En-Arrh. Subsequently, Damian Wayne was set up to be both the next Robin and (as an adult) the Batman of a nightmarish future Gotham. In due course Morrison revived the Club of Heroes, an international group of adventurers each inspired by Batman; and positioned Dick Grayson to succeed Bruce under the bat-eared cowl. Bruce was gone for over a year (in real time) and Dick remained Batman (“a” Batman) for more than two years, only going back to being Nightwing with the New 52 relaunch.

It’s overly simplistic, and probably grossly inaccurate, to say that Dick-as-Batman and Damian-as-Robin were Morrison’s two big structural changes to the Batman line. However, it’s still worth pointing out. Morrison brought a new dynamic to the Dynamic Duo (sorry, couldn’t resist) and Dick and Damian showed up across DC’s superhero line in books like Justice League of America, Teen Titans, a new World’s Finest miniseries and Supergirl. This in itself wasn’t all that revolutionary. In fact, at the same time, the Superman books were using the “New Krypton” framework to shake up their own casts. However, Morrison intended to use as much of Batman’s seventy-year history as possible -- from the sci-fi stories of the 1950s and early ‘60s to the globetrotting ‘70s and ‘80s and the grim early ‘90s -- so for his radical status quo to be “ratified” by appearances in other books was more significant than just a set of routine crossovers.

In that regard, it may be more telling that Morrison’s “Batman Incorporated” concept didn’t get as much play in the shared superhero universe. At first the title seemed like a way to refocus the larger story on Bruce Wayne (headlining both the Morrison-written Incorporated and a new Dark Knight title from writer/artist David Finch) while leaving Dick and Damian as the stars of the still-popular (but Morrison-free) Batman and Robin. In November 2010, Batman Incorporated wasn’t just the Bat-line’s latest way to expand, it was the next step in Morrison’s transformation of the Batman identity. A year later, though, Incorporated was on hiatus and the concept had been reframed into the background of the new Batwing series (and brief mentions in other Bat-books). When Incorporated returned in the spring of 2012, it seemed increasingly vestigial, although Damian’s death earlier this year still ripples through the rest of the line.

* * *

So what about Issue 13 itself? Basically, it’s told from the perspective of Commissioner Gordon, arresting and interrogating a bruised and bloodied Bruce Wayne about the deaths of his son and Talia al-Ghūl. Flashbacks reveal Batman and Talia’s final fight in the Batcave, the two Bat-allies who play key roles (both of whom had previously died rather prominently), and the Batman Incorporated figures who worked around the globe to stop Leviathan’s plans. It’s perhaps more notable for the style than for the plot, as most of the big plot developments amount to hand-waving.

That’s not all bad, because it allowed me to linger on the various homages and Batman counterparts. Talia’s outfit uses elements of Thomas Wayne’s Bat-Man getup, she swordfights with Batman like her father did, and she and Batman lock lips in a very Neal Adams sort of way. Like surrogate parents, Patrolman Gordon and Leslie Thompkins join young Bruce under the Crime Alley spotlight. Leviathan’s weaponized kids parody not just Damian, but the idea of “Robin” generally; and Leviathan’s female agents wear variations of Kathy Kane’s old yellow-and-red Batwoman garb. (Remember, Kathy became Batwoman originally because she idolized Batman and figured she could do just as well.) Similarly, seeing the new Knight reminds readers that sidekicks tend to take on their late mentors’ identities. However, sometimes the mentors return (and sometimes the sidekicks don’t): Talia reminds Batman that her parents died too, and her father more than once. Indeed, in a very real sense the issue centers around the work of writer Denny O’Neil, both with characters he created and one he killed.

In short, it’s yet more Morrison as ecumenist, holding fast to the idea that every Batman story still “happened,” or at least still has value, despite all that the years have done to them. The New 52 relaunch is just another cosmic shift which Morrison must work around, but which doesn’t necessarily change anything. Like Geoff Johns’ sprawling Green Lantern arcs, the longtime readers appreciate the nods, but more practical concerns mean that the focus must always be on what’s happening now.

The issue ends on a note of rebuilding: not just Wayne Tower, but the League of Assassins and the rest of the Demon’s Head organization. There’s also a scene that could allow the return of Damian Wayne, although I don’t think that’ll happen any time soon (if at all). Writers Scott Snyder and Peter Tomasi have both used Damian to good effect, but the lovable little punk was Morrison’s character, and I suspect DC will want the next Robin to not be identified so closely with any particular professional.**

But I digress. Over the past seven years, Morrison and his artistic collaborators (including Andy Kubert, J.H. Williams III, Tony Daniel, Frank Quitely, Frazer Irving and Yanick Paquette) took Bruce Wayne and company around the world and across time and space. They made old and new lovers into deadly enemies, rehabilitated wayward ex-partners, and questioned the integrity of the Wayne lineage. They made “Batman” something that could be shared, even as they focused on the hole in Bruce’s heart that would never heal. For a while, they even brought back the yellow oval.

For all of those reasons, I’d say that yes, Morrison did quite a bit to “fix” Batman. Back in 2010 I wrote that Morrison had made Bruce both “calmly confident,” if not outright “enthusiastic,” about the potential of “Batman.” Even without regard to the Batman Incorporated organization, that attitude has prevailed, particularly in Scott Snyder’s work. Batman is still driven, determined, and at the top of the superhero org-chart -- but he’s no longer “broken,” and Grant Morrison is a big reason why.

+++++++++++++++

* [Paul Dini took over Detective Comics at about the same time, and wrote 24 issues from cover-date September 2006 through cover-date March 2009 before moving on to 16 issues of Streets of Gotham and 10 issues of Gotham City Sirens.]

** [If memory serves, writer Gerry Conway and artist Don Newton introduced Jason Todd, writers Marv Wolfman and George Pérez and artist Jim Aparo introduced Tim Drake, and writer Chuck Dixon and artist Tom Lyle introduced Stephanie Brown; but arguably none of them had any special influence over those characters’ later directions. Now one of the candidates appears to be Frank Miller’s creation Carrie Kelly.]