With the end of Geoff Johns’ tenure on Green Lantern and Grant Morrison’s upcoming farewell to Batman, a fan’s thoughts turn naturally to other extended runs. Marv Wolfman wrote almost every issue of New (Teen) Titans from the title’s 1980 preview through its final issue in 1995. Cary Bates wrote The Flash fairly steadily from May 1971's Issue 206 through October 1985's first farewell to Barry Allen (Issue 350). Gerry Conway was Justice League of America’s regular writer for over seven years, taking only a few breaks from February 1978's Issue 151 through October 1986's Issue 255.

However, in these days of shorter stays, I wanted to examine some of the runs that, despite their abbreviated nature, left lasting impressions. At first this might sound rather simple. After all, there are plenty of influential miniseries-within-series, like “Batman: Year One” or “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?,” where a special creative team comes in to tell a particular story. Instead, sometimes a series’ regular creative team will burn brightly, but just too quickly, leaving behind a longing for what might have been.

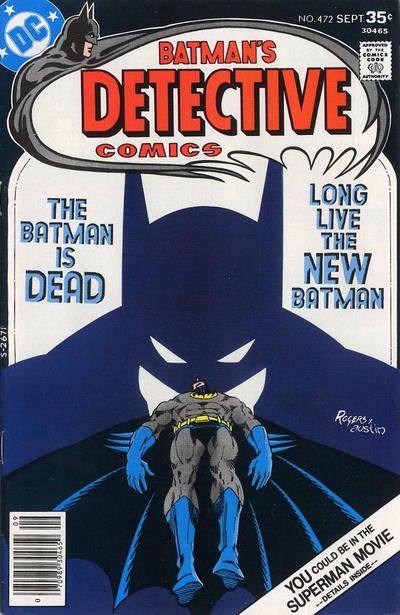

A good example of this is found in Detective Comics #469-76, written by Steve Englehart, penciled by Marshall Rogers and inked by Terry Austin (after Walt Simonson penciled and Al Milgrom inked issues 469-70). Reprinted in the out-of-print Batman: Strange Apparitions paperback, and more recently (sans Simonson/Milgrom) in the hardcover Legends of the Dark Knight: Marshall Rogers, these issues introduced Silver St. Cloud, Rupert Thorne, Dr. Phosphorus and the “Laughing Fish,” featured classic interpretations of Hugo Strange, the Penguin and the Joker, and revamped Deadshot into the high-tech assassin he remains today. Tying all these threads together is Bruce Wayne’s romance with Silver, which for my money is the Bat-books’ version of Casablanca. It’s the kind of much-discussed run that seems like it should have been longer. Indeed, I suspect it’s one of the shorter runs in CSBG’s Top 100 list.

Past that, however, it was hard for me to come up with comparably-well-known short stints -- and by “short” I mean generally fewer than 12 issues. Many gone-too-soon teams actually hung around for a little while, and some short runs don’t seem that well-known. For example, if DC announced today that the new creative team on Action Comics would be writer Gail Simone and penciler John Byrne, I suspect it would get a lot of fanfare. However, Simone, Byrne and inker Nelson DeCastro were the Action team for issues 827-31 and 833-35 (July 2005-March 2006). Their run is collected in Superman: Strange Attractors, and it features a revamped Doctor Polaris, fights with Black Adam and Doctor Psycho, and a couple of good Lois Lane subplots.

Simone and Byrne later worked together on early issues of All-New Atom, the series that put a size-changing belt on Ryan Choi, and which lasted 25 issues. In fact, DC has plenty of fondly remembered series that ran for about as long, including Tom Peyer and Rags Morales’ Hourman (25 issues), D. Curtis Johnson and J.H. Williams III’s Chase (10 issues and a lot of guest appearances), Grant Morrison, Mark Millar and N. Steven Harris’s Aztek (10 issues), Bob Rozakis and Stephen DeStefano’s ’Mazing Man (12 issues and three specials), Martin Pasko and Rick Burchett’s Blackhawk (16 issues and two specials, plus the original Action Comics Weekly serial), Len Kaminski, Steven Grant and John Paul Leon’s Challengers of the Unknown (18 issues), Dan Raspler and Dev Madan’s Young Heroes in Love (18 issues), and John Francis Moore and Paul Guinan’s Chronos (12 issues) -- and that’s just off the top of my head. Most of those feature updated versions of classic DC characters, which ironically is no guarantee of longevity. The others are quirky takes on superhero tropes, and those are never easy sells. The cumulative effects of all these short-lived series included populating crowd scenes in Big Event miniseries, and giving the publisher a “farm system” for calling up characters when it needed an extra shot of nostalgia. As a result, DC has plenty of characters it can bring out of limbo and either turn into superstars or let fade away.

With all that said, one abruptly-cancelled series which did come to mind was Jack Kirby’s original OMAC (eight issues, September/October 1974-November/December 1975). The series-ending cliffhanger was finally resolved in a series of backup stories (by Jim Starlin) starting in September 1978's Kamandi #59 and continuing in Warlord #37-47 (September 1980-July 1981). However, those stories aren’t nearly as memorable as the originals, and particularly Kirby’s first-issue combination of sex, violence, corporate culture and rebellion. John Byrne wrote and drew an OMAC miniseries in the early ‘90s, the character’s distinctive look was adapted for an army of killer cyborgs, and the recent New 52 series (by Dan DiDio and Keith Giffen) tried to channel some of the old Kirby energy. Still, OMAC’s eight issues aren’t exactly the same as eight issues of a mainstay like Detective or Action.

Indeed, a Detective backup feature is arguably closer to OMAC’s idiosyncracy than the work of Englehart/Simonson/Rogers. I’ve written before about how Archie Goodwin and Walt Simonson’s “Manhunter” has largely resisted being co-opted by the demands of a shared superhero universe, and I think a big part of that comes from its definite ending. Goodwin and Simonson told Paul Kirk’s story so completely and so well that virtually nothing was left to say. Naturally, others have used the Council and its clones, but the original stories stand alone.

Compare OMAC and “Manhunter” with Gerry Conway and Don Heck’s Steel, The Indestructible Man (five issues, March 1978-October/November 1978). Today he’s “Commander” Steel, but he hasn’t changed all that much from his ‘70s debut. However, I suspect he got a lot more exposure from writer Roy Thomas in All-Star Squadron than he ever did in his initial five-issue run. That came a few years after Steel #5, though; and that makes the Indestructible Man something of an outlier where DC’s new-for-the-‘70s heroes were concerned. After all, Conway and Al Milgrom’s original Firestorm series lasted five issues, but ‘Stormy went pretty quickly into a backup series in The Flash, joined the Justice League, and was back in his own ongoing by the time Steel was getting to know the All-Stars. Likewise, Tony Isabella and Trevor von Eeden’s Black Lightning lasted 11 issues (April 1977-September/October 1978), but fairly soon found new backup-series homes, first in World’s Finest Comics and then in Detective, before joining Batman and the Outsiders.

Actually, Madame Xanadu is probably close to Steel in terms of publishing history. Her first series was Doorway to Nightmare, which lasted (yes) five issues (January/February 1978-September/October 1978). After that there was a Madame Xanadu Special (1981) and appearances in various superhero books before becoming part of John Ostrander and Tom Mandrake’s Spectre supporting cast in 1993.

So where does all that leave us? Well, not to lay it all at Walt Simonson’s feet, but his four issues of Metal Men (issues 45-49, April/May 1976-December 1976/January 1977) are among the best Metal Men stories around. Written by Steve Gerber, Martin Pasko and Gerry Conway, they were collected in the long out-of-print Art of Walter Simonson paperback. There, Simonson himself called Metal Men “some of the silliest (and most enjoyable) work I’ve done.” As it happens, after fighting Chemo and the Platinum Man, our heroes took on Eclipso, another character DC pulls out of limbo every now and then.

And while we’re in ‘70s-revival mode, I want to mention the first couple of arcs of DC’s relaunched Showcase. Brought back in the same wave that revived Teen Titans, All Star Comics, and other Silver Age stalwarts, Showcase #94-96 introduced the New Doom Patrol (from writer Paul Kupperberg and artist Joe Staton), followed by the origin of Power Girl in issues 97-99 (written by Paul Levitz and penciled by Staton). Of course, each of these features has enjoyed varying degrees of popularity over the years -- particularly the new Patrollers, who have since either died or been changed fairly radically -- but in terms of short, influential runs, you could make a good case for those six Staton-penciled issues of Showcase.

Finally, let’s go back to the big characters, and in fact to DC’s biggest. The 1986 revamp of Superman had John Byrne doing most of the heavy lifting, since he was writing and pencilling both Superman and Action Comics. However, writer Marv Wolfman and penciler Jerry Ordway were there at the beginning, too, as the creative team on Adventures of Superman. Wolfman also contributed to the “new” evil-businessman Lex Luthor, and indeed Luthor was a focus of Wolfman’s 12 issues. He and Ordway also introduced Emil Hamilton, Cat Grant, Bibbo Bibbowski, Jerry White, José “Gangbuster” Delgado and a group of mysterious telepaths called the Circle. OK, you probably don’t remember the Circle, but the others were longtime members of the Super-cast. Wolfman’s focus was on the people around Superman, and he emphasized character studies over big superhero action (although there was a lot of that, too). Ordway stayed on the book after Byrne succeeded Wolfman, and Ordway eventually became Adventures’ writer/artist. Wolfman’s 12 issues are at the outer edge of my “short-lived” definition, but they certainly set the tone for street-level Superman stories.

A few years later, Wolfman’s longtime collaborator George Pérez was also part of the Super-team, plotting and penciling Action Comics, starting with the second Annual and including issues 643-45 and 647-53 (July 1989-April 1990). Pérez’s contributions centered around Kryptonian culture, specifically the egg-with-an-agenda known as the Eradicator. During Pérez’s run, the Eradicator built the Fortress of Solitude and gradually rewired Supes’ brain toward a more Krypton-friendly mindset. (The Kents snapped him out of it.) Pérez also introduced Maxima, redesigned Brainiac into something approaching his old android self, and contributed to a few Adventures of Superman issues featuring the Eradicator, including one that turned Jimmy Olsen into an “Elastic Lad.”

Still, for a long time the biggest changes to the Superman mythology came from a short-term writer. January 1971's Issue 233 was Denny O’Neil’s first issue as writer of Superman. You know it from the famous Neal Adams cover declaring “Kryptonite Nevermore!” and you may well remember the scene of Superman (drawn by Curt Swan and Murphy Anderson) munching an inert chunk of Kryptonite like it was one of Ma Kent’s brownies. Issue 233 also featured Clark Kent’s reassignment to TV news and the introduction of a new antagonist, the “Quarrmer” (from the dimension of Quarmm, of course) a/k/a the “Sand Superman.” This silicate super-sibling was also supposed to siphon away half of the Man of Steel’s power level, making him less of a demigod. O’Neil wrote nine issues of Superman (#233-38, 240-42), many of them involving ordinary folk caught between Superman and the menace du jour. Once he left, the stories eventually went back to more cosmic fare, and Superman was once again so strong that a de-powering was part of the ‘86 revamp -- but Clark stayed on TV into the ‘80s, Kryptonite remained uncommon, and the Quarrmer got his own revamp, courtesy of (yes!) Walt Simonson’s 1992 Superman Special. (O’Neil’s editor, Julius Schwartz, came aboard with Issue 233 as well, and he stayed until Alan Moore wrote the last pre-revamp issue of Action Comics.) O’Neil might have made a bigger splash with Batman, Green Lantern, Green Arrow, and Wonder Woman, but one of his lesser-known assignments helped redefine Superman for the Bronze Age.

That’s what fascinates me about the short-timers on these long-running series. At their worst, there’s a lot of marking time -- just putting out something, anything, as long as it fills out an issue -- and/or a series of sales-goosing stunts. Twelve-issue arcs like Superman’s “For Tomorrow” and “Grounded,” Wonder Woman’s “Odyssey,” and Batman’s “Hush,” offer another way to attract readers, even though those readers might not stick around after the thing’s over (or, worse, might wait for the collection). Instead, the idea of a regular creative team getting its own open-ended opportunity on a particular title is more appealing, because you don’t know what they’re going to do or how long it’ll take them to do it. Writers and artists who stick with a particular feature for the long term have more of a chance to make a lasting impression, which is why we have lists like CSBG’s Top 100 Runs. It makes the short-term successes seem even more special.

(Of course, it never hurts to have Walt Simonson on board ...)