Note: Due to my travel schedule, the Futures Index is taking a break this week. There will be a double dose next week to get us back on track.

Something I didn’t mention in last week’s post about The Multiversity #1 is the persistent notion that corporate-controlled characters have, for lack of a better phrase, “lives of their own.” In other words, we know how Superman, et al., are “supposed” to act, based on common, recurring elements, which are ostensibly independent of any particular creative team. Because The Multiversity offers a prime opportunity to play around with those elements and the expectations they engender, this week I wanted to go a little more in that direction.

* * *

We begin with Batman, and specifically a scene from the now-classic Batman: The Brave and the Bold cartoon. “Legends of the Dark Mite,” written by Bat-guru Paul Dini, features a brief-but-incisive dig not just at fans, but at the corporate culture which has nurtured the Caped Crusader over these past 75 years. See, Bat-Mite wants to see his hero fight a supervillain, but Batman just wants the little guy to vamoose, and suggests the imp summon Calendar Man. Yadda yadda yadda, Calendar King has killer Easter Bunnies.

“These creatures might be too over the top to be Batman villains,” Bat-Mite muses.

“I really don’t see how,” Calendar King replies.

“Let’s see what the Batman fanboys think!” Bat-Mite exclaims.

The scene switches to a crowded convention panel, where an audience member offers a nasal comment: “I always felt Batman was best suited in the role of gritty urban crime detective ...? But now you guys have him up against Santas? And Easter Bunnies? I’m sorry! But that’s not my Batman!”

After the panelists huddle, Bat-Mite reads their prepared statement: “‘Batman’s rich history allows him to be interpreted in a multitude of ways. To be sure, this is a lighter incarnation, but it’s certainly no less valid and true to the character’s roots as the tortured avenger crying out for mommy and daddy.’ And besides -- those Easter Bunnies looked really scary, right?”

That mollifies the crowd for the most part. It also sounds a lot like any number of Bat-retrospectives -- including some I have written -- which seek to reconcile one set of stylistic excesses with another. Today, the “lighter incarnations” are celebrated, not just by shows like B:B&TB but in the resurgence of Batman ‘66 material. Still, ‘twarn’t always so. When Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams came along in the late ‘60s, and especially when Frank Miller, Klaus Janson and Lynn Varley presented The Dark Knight Returns in 1985, those stories weren’t just diametrically opposed to the work of Dick Sprang and Adam West, they were almost mutually exclusive.

Of course, we can say that about Batman because we can point to twelve months’ worth of Detective Comics stories from 1939-40 which are full of gritty urban crimefighting (and, by the way, no Robin). Written and drawn by Batman’s creators Bill Finger and Bob Kane, along with the likes of Gardner Fox and Jerry Robinson, they’ve got good Golden Age credentials as well. I say all that not to debate the merits of 1939 Batman versus 1955 Batman, but to note that O’Neil, Adams, Miller, etc., each found support for his own approach in those early stories.

With other characters, it’s not so easy. I have written previously about a singular Superman interpretation, and about the extent to which Wonder Woman has varied from William Moulton Marston’s vision. With those characters, I suppose there’s a question -- which I don’t intend to settle today -- about whether the accumulated work of all those creative teams (and multimedia interpretations) have improved upon their creators’ work. Saying that it did might sound like a rationalization, but it also reinforces this notion that these characters have an existence apart from their creators’ work.

* * *

Of course, as a practical matter they do have just such an existence. More than likely it’s what The Multiversity #1 calls the “anti-death equation,” and what we call relaunches and reboots. DC Comics uses these kinds of narrative maneuvers to keep those characters marketable. However, to the extent a relaunch, reboot or reinterpretation diverges from the original creators’ work, it undermines the value of that work.

That’s where the Multiverse comes in. It can provide “homes” for those original creations, as in the Silver and Bronze Ages. It can also facilitate an array of variations, from the classic Imaginary Stories and their Elseworlds descendants to the current 52-part Orrery. In fact, while Multiversity showcases the variations (i.e., the Superman of Earth-23 and the Pax Americana of Earth-4), its Earth-5 will apparently be a pretty faithful homage to old-school Captain Marvel.

Does that fidelity make Earth-5 the home of the “real” Marvel Family? It’s tempting to say yes, particularly since the MF-ers (couldn’t resist) have been contorted pretty drastically over the past several years to make them fit better into the larger superhero line. Back in the day, Earth-S allowed the Marvels to be preserved virtually inviolate, so that the Shazam! comic’s creative teams could pick up where their predecessors at Fawcett had left off. That didn’t stop Shazam! from going a little grim ‘n’ gritty in the late ‘70s, but at least it postponed the changes for a few years.

This is not to say that all change is bad, and all comics should read just the way they did when we first found them. Rather, it’s about choosing either to honor creators’ original intentions, or to break with those intentions in the name of “updating.” In the starkest contrast, the former gives everyone the dignity they deserve, whereas the latter treats characters as commodities.

Naturally, the actual situations are not as cut and dried, especially for the legacy-type characters. How much did Julie Schwartz, John Broome, and Gil Kane’s Hal Jordan stories need to honor the work of Green Lantern creators Bill Finger and Martin Nodell? Did Finger and Nodell just want to tell stories about a guy with a magic wishing ring, or were they really attached to the purple cape and taxi-driving sidekick? What about Schwartz, Kane and Gardner Fox’s size-changing Atom, which was nothing like the stocky brawler created by -- and I had to look this up, which tells you something -- Ben Flinton and Bill O’Conner? If there’d been an Internet in the early ‘60s, I bet there’d have been Al Pratt fans complaining about the Atom legacy, and wondering loudly why the new guy even had to use that name. “What about Dwarfstar? That’s even more specific, ‘cause it comes straight from his origin!”

(Actually, Wikipedia says that none other than Golden Age uber-fans Jerry Bails and Roy Thomas wanted to update Al Pratt by making him even smaller, a la Doll Man, so maybe it would’ve gone down more smoothly.)

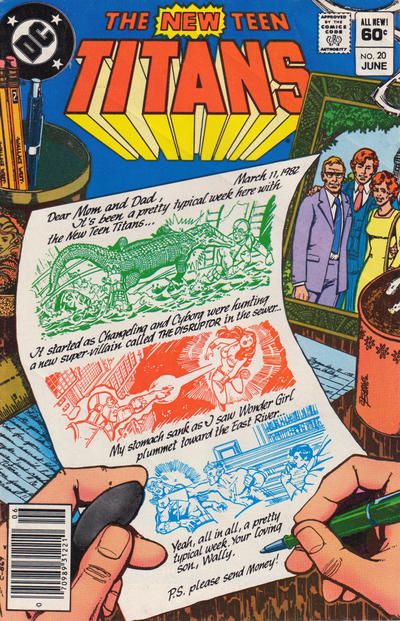

Anyway, to put it bluntly, sometimes an update helps refocus one’s attention on the attributes which matter, not the details that distract. Fans of the Wally West Flash liked to point out that Barry Allen was objectively more boring and therefore didn’t need to be revived. There’s a lot to that argument, but I will say -- speaking as someone who’s been a Wally fan since the Kid Flash days -- Wally wasn’t exactly Mister Personality either. In New Teen Titans, Marv Wolfman and George Pérez made Wally “the normal one.” He didn’t want to be a superhero, he just wanted to go to college. Raven had to zap him into crushing on her so he’d join the team. An entire issue was built around one of his letters home, telling his perfectly bland parents -- who didn’t even have names, and who got more interesting almost by default when they showed up in Wally’s Flash series -- about his exciting adventures in the big city. Wally’s home life in NTT was basically an endless loop of that panel from Amazing Fantasy #15 where Peter Parker sits down to a big stack of Aunt May’s wheatcakes while Uncle Ben looks on beatifically.

Now, in light of our questions from a couple of paragraphs back, how does that square with Gardner Fox and Harry Lampert’s vision for Jay Garrick, or with John Broome and Carmine Infantino’s Barry Allen? Making things more complicated is the fact that when Wally took over for Barry, Jay was semi-retired, but still calling himself the Flash. (Seriously, when Wally proclaims in Crisis on Infinite Earths #12 that “as of today, the Flash lives again,” Jay’s sitting right there, nice enough not to clear his throat.) Therefore, DC could claim to have preserved the work of Fox, Lampert and their successors on Jay, while at the same time publishing the adventures of a totally separate character who happened to share the same codename and powers. The transition from Barry to Wally just switched out the guy behind the mask and tweaked the power set somewhat. In that respect DC isn’t so much in the business of publishing “Flash stories” as it is publishing Jay, Barry and Wally stories.

* * *

That’s a lot to digest, I know. It’s a long and twisty road from “only one Superman” to the legacy structure, but I think there are some common principles. You can also look at a character’s treatment in three basic ways:

- the original character (i.e., the Siegel/Shuster Superman);

- a version that’s been altered out of “necessity” (the Earth-One Supes); or

- a version that’s been altered for a particular purpose (the Earth-23 Supes).

Offhand I’d say the vast majority of DC characters fall into the second category, even more so now that the Golden Agers have been shelved.

Still, what does this mean for us superhero-comics readers? Well, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to reconcile my love of Silver and Bronze Age Superman with my awareness of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s horrible treatment, and that’s produced some significant cognitive dissonance. The Siegel family’s legal battles with DC, and the resulting “... by arrangement with the Jerry Siegel family” credit, have gone a long way to mitigate that; but Siegel and Shuster were hardly alone. The more we know about the histories of these characters, the better-equipped we are to judge the conduct of their caretakers.

See, we can say that Superman is “acting out of character,” but we need to be careful about where that “character” comes from. Kane, Finger, and Robinson created Robin, but Wolfman and Pérez created Nightwing. Jack Burnley and a passel of editors are credited with creating Starman, but -- just about 20 years ago, in fact -- James Robinson and Tony Harris gave the world his son, Jack Knight. Heck, Wally West went through so many developments at the hands of so many different creative teams that each one seems to have been responsible for a separate trait.

My point is that if we get too wrapped up in the behavior of particular characters, we can lose sight of the real people behind them. Jack Knight didn’t appear in a whole lot of comics outside of Starman (the first few issues of JSA being a notable exception), so not a lot of creative folks produced his adventures outside of Robinson, Harris, and Peter Snejbjerg. More recently, Grant Morrison and Andy Kubert created Damian Wayne (based, I must note, on the work of Mike W. Barr and Jerry Bingham in Batman: Son of the Demon), and Morrison and an array of artists were largely responsible for him over the next several years. Damian got a little more exposure to the wider DC world, appearing in various other Bat-books and related fare like Teen Titans, but he was a pivotal part of Morrison’s larger Batman story, and Morrison and Chris Burnham chronicled his eventual death. Now Peter Tomasi and Patrick Gleason (again, with help from Andy Kubert) are in the middle of “Robin Rises,” an arc which will either restore Damian to life or bring an appropriate amount of closure to his death. Personally, as mordant as it might sound, I’d like it to be the latter. Damian might have started out as Morrison and Kubert’s, but Tomasi and Gleason told their share of effective Damian stories as well. Making “Rises” the last Damian story would be a nice way to acknowledge these professionals’ fine work.

* * *

Look, I’m not blind to the realities of corporate-controlled superhero comics. As long as a character is popular, a company will try to exploit it. Multiverses and legacies are just in-story means to those ends. However, multiverses and legacies can also facilitate some pretty innovative spins on established concepts. A big chunk of what we know as the modern “DC Universe” came from the ability to remake characters like the Flash and Green Lantern from the ground up. That implies a set of “core values” -- super-speed, magic ring -- are all that’s needed to define a character. In that light, and after so many years and so many stories, it’s easy to give these characters their independence. Who wouldn’t argue that Wonder Woman is bigger than the Finches, Azzarello and Chiang, Simone and Scott, Byrne, Pérez, et al.?

We can say that, but we must also remember that each of those professionals brings his or her unique talents to those characters. Perhaps the crassest form of Multiversal exploitation came during the year-long Countdown miniseries (2007-08), when it and its spinoffs populated various parallel universes with settings from familiar Elseworlds like Superman: Red Son and the Bat-Vampire trilogy. There, the alternate superheroes existed mostly for shock value, if not outright cannon fodder (as in the Countdown: Arena miniseries). Did you like Darwyn Cooke’s Wonder Woman from New Frontier? Watch her get knocked unconscious by her Victorian counterpart from Bill Messner-Loebs and Phil Winslade’s Amazonia! Wonder Woman is bigger than those professionals, but that doesn’t mean their work should be recycled so capriciously.

Instead, the focus should be on recognizing each professional’s unique contributions, and not forgetting them, regardless of whether they’re retained or improved upon. These characters only “got big” because of the countless comics folks who produced their adventures. Everybody’s got something to say, and if you work in comics, you’ve got a heck of a platform. We don’t want your efforts, good or bad, to be lost in the shuffle.