Welcome to Greatest Comic of All Time, a new weekly column spotlighting great comic books that don't appear on the bestseller charts or canon lists or big-box bookstore shelves. They are the property of the back issue bins and thrift store crates and swap meet hawkers of America, living like the comics medium itself in the unremembered crags and pockets of publishing history. It is a testament to the form's strength that overlooked and forgotten work as potent as the celebrated masterpieces exists, and it is a testament to comics' true devotees that these diamonds still emerge from the rough to shine once more for those who seek them out.

Thor #160, composed and illustrated by Jack Kirby, inked by Vince Colletta, dialogued by Stan Lee. Cover-dated January 1969. Published by Marvel Comics/Perfect Film & Chemical Corporation.

How acquired: Thrown in on top of a box of late-'80s/early '90s superhero comics given to me by a guy who worked at an iron furnace company whose building I used to hang around. "This one's actually good," is the quote I remember.

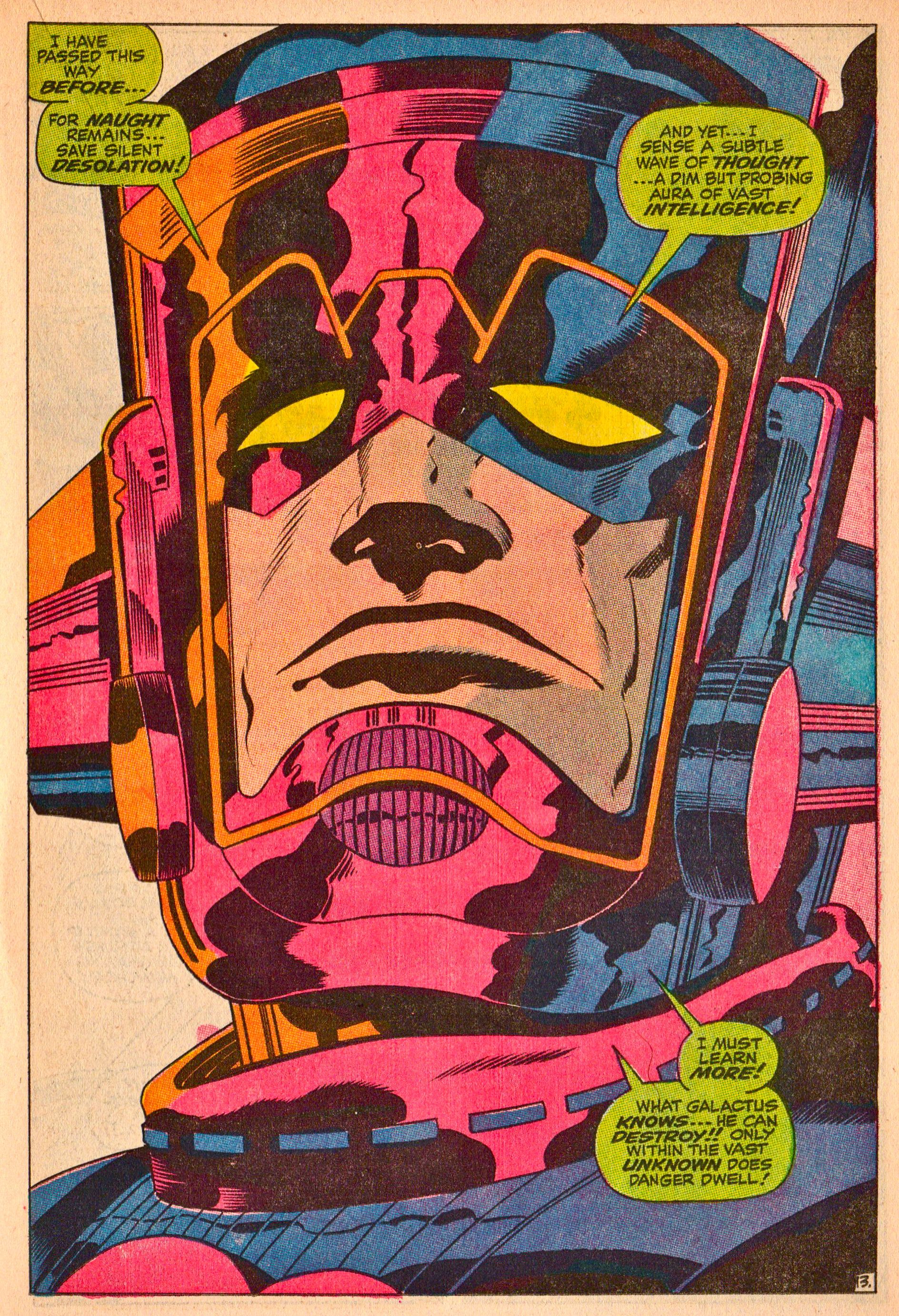

Best single drawing:

Full effect.

The history lesson: By 1969 Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, probably the most famous and influential artist-writer team in the history of comics, were a partnership in little more than name. Lee, famed as the imagination that built Marvel Comics' then-new superhero empire, had been pulled away from the workaday world of comics writing by mainstream media notoriety and the possibility of professional advancement, while Kirby, the real font of ideas at Marvel, labored on in an increasing state of creative solitude dissatisfaction, composing whole comics that Lee would later come in a dialogue from notes provided by the artist. That Lee is the one who got famous and became a household name is nothing too remarkable -- show me the successful man whose climb used no human bodies as its footholds -- but the historical fallacy that Lee was the wellspring of Marvel should be pointed out as just that. It's hard to hold anything against Lee, especially given the breathtaking viciousness with which Kirby, his descendants, and the rest of his era's creative class were treated by the companies they worked for. Really, it's rather incredible that anyone who's done work in corporate comics has had as much success as Lee, and if it weren't for that success he would just be another aging, passed-over creator in the raft of them that Kirby was eventually consigned to. But especially at this moment in time, with a film featuring Kirby's creations raking in unprecedented amounts of money under the name "Marvel's The Avengers", a Stan Lee executive production, it's important to remember where the ideas really came from.

Though this comic has been reprinted a few times, it's never been widely available in a satisfactory form: readers can choose from a stupendously overpriced version with a poor recoloring job, a black and white reproduction, or a ruthlessly edited compilation of this and a few other Kirby issues featuring the same characters. Get the original.

Why it's the greatest comic of all time: There's no better example of Kirby's particular genius out there, really. Though he's justly lauded for the sweep and vastness of his visions, the broadness of the strokes he painted his worlds with, the form Kirby was master of was a concise, even abbreviated one: the 20-odd-page single comic book issue. Though his long, arching storylines have a grandeur all their own, Kirby is most effective in a single, thinly jacketed dose, like a bullet. His stories are more presentational than narrative, with a logic unique to their artist and perfect for comics. The individual drawings on the average Kirby page are dangerously disconnected from on another, compositions that stand alone and only flow smoothly because of the titanic amount of movement put into each one. Similarly, Kirby most often put forth ideas without developing them beyond what they were introduced as, even if they went on to inform hundreds or thousands of pages of story. The novelty and imaginative zeal of the raw archetypes that were Kirby's characters, his settings, his cultures and his technologies, have enough to them on the surface that there is little need for further exploration. And when different Kirby surfaces clash against each other like tectonic plates, the earth moves.

There isn't much to the plot of Thor #160, and there doesn't need to be. Kirby simply dogpiles idea onto world-beating idea for 20 pages here, each one so impressive that it stops mattering whether or not they coalesce into something greater than the sum of their parts. The sheer number of fabulous characters the comic displays would be story content enough by itself, transforming the fairly simple chronicle of a team of heroes traveling outer space seeking a villain too powerful to be allowed to live any longer into a modern-day fairy tale, in which every personality is something far beyond human, every line spoken by someone strange and wonderful. It operates far above the human plane that was Lee's main contribution to Marvel. This is pure Kirby, gods and monsters and things somewhere in between fighting unfathomable wars with undreamed of weapons in realms no human eye has ever seen. In addition to the lusty, purehearted God of Thunder, readers are introduced or reintroduced to Odin, the stormy patriarch of the Gods; the Colonizer Tana Nile, a psychic alien who once sought to enslave the earth but now comes to Thor beseeching him to help her people; the robotic Recorder, created to observe and store data but possessed of uncannily human feelings; Ego, the Living Planet; and the character who best embodies the often-named Kirby virtue of Power -- Galactus, world mover and world ravisher.

Galactus is a fascinating creation, one whose simultaneous simplicity and complexity isn't often found outside religious text or myth. The spontaneous creation of a cosmic catastrophe, he scours the universe searching out new worlds to destroy, not because of any inner evil, but simply because he must do so or perish. Galactus is Destruction personified in the best costume Kirby ever drew, the inevitable result of all the power his comics unleashed on the page, the balancing force to everything in the universe that was designed to create, including Kirby himself. Kirby seemed to sense that in Galactus he had created his own antithesis, and tread carefully around the character, literally giving him space -- the full-page headshot above being only one example of the muralistic treatment he receives in the issue. Though the next ten issues of Thor would go on to relate Galactus' origin story, the real truth of what he is lies in that one drawing, and in Lee's pitch-perfect dialoguing of it: something so great and powerful that it is incapable of comprehending the misery it wreaks, and uncaring for it. He is more idea than character, and though Kirby would go on to create a God of Evil in Darkseid, nothing that sprang from his mind was ever as frightening as the iconic reading of Galactus we get here, a pure, emotionless, unexplained unmaker of things.

On these pages Galactus finds a worthy foe in Ego, the Living Planet, but more interesting yet is Kirby's introduction, late in the game, of the Wanderers, an alien race whose planet was Galactus' first conquest. Here the cosmic saga takes a twist both personal and Biblical: the Wanderers' nameless leader recalls no one more than Moses, who led his people on an age-long journey after barely avoiding destruction. The Wanderers themselves recall nothing more than a band of intergalactic Jews, without a homeland and sentenced to an endless search across the spaceways. Kirby himself was Jewish, and it's impossible not to read the story of the Wanderers as a fascinating statement of cultural identity from the King of Comics. In classic Kirby fashion, however, the Wanderers journey not toward respite, but revenge, and when Thor challenges Galactus, they follow. The subtexts here are nothing short of electric -- the distinctly Semitic Wanderers using a blonde-haired, blue-eyed Norse god as the instrument of their final revenge is a stone jawdropper -- but in the end it's more compelling to follow the story as what it is than what it hints at. When Galactus and Ego finally clash, the immediacy of Kirby's searing drawings supersedes all else, and it becomes useless to compare art so vigorously alive with tales of civilizations long passed on. Printed in garish ink on yellowed, brittle paper, this is the rare superhero comic that actually lives up to the genre's billing as "modern myth".

Kirby made his stories for the world he lived in, and allowed his ideas to stand tall as they were. This comic is certainly more than its pages and drawings and words, but the artifact of Thor #160 alone tells a fascinating story: one of a man who was crushed beneath the heel of industry, but whose blood burned so hot that his service to the overlords who treated him so ruthlessly left behind paper objects more powerful and compelling than anything hundreds of millions of dollars and a small army of filmmakers are capable of producing. Like the gods whose stories he continued from the ancient myths that birthed them, Kirby will outlive us all.

Cover price: 12 cents.