The greatest comics of all time don’t appear on bestseller charts or canon lists or big-box bookstore shelves. They are the property of the back issue bins and thrift store crates and convention tables of America, living like the medium itself in the unseen crags and pockets of publishing history…

Nick Fury, Agent of... S.H.I.E.L.D. #2, by Jim Steranko. Cover-dated July 1968. Published by Olympia Publications, Inc./Marvel Comics Group.

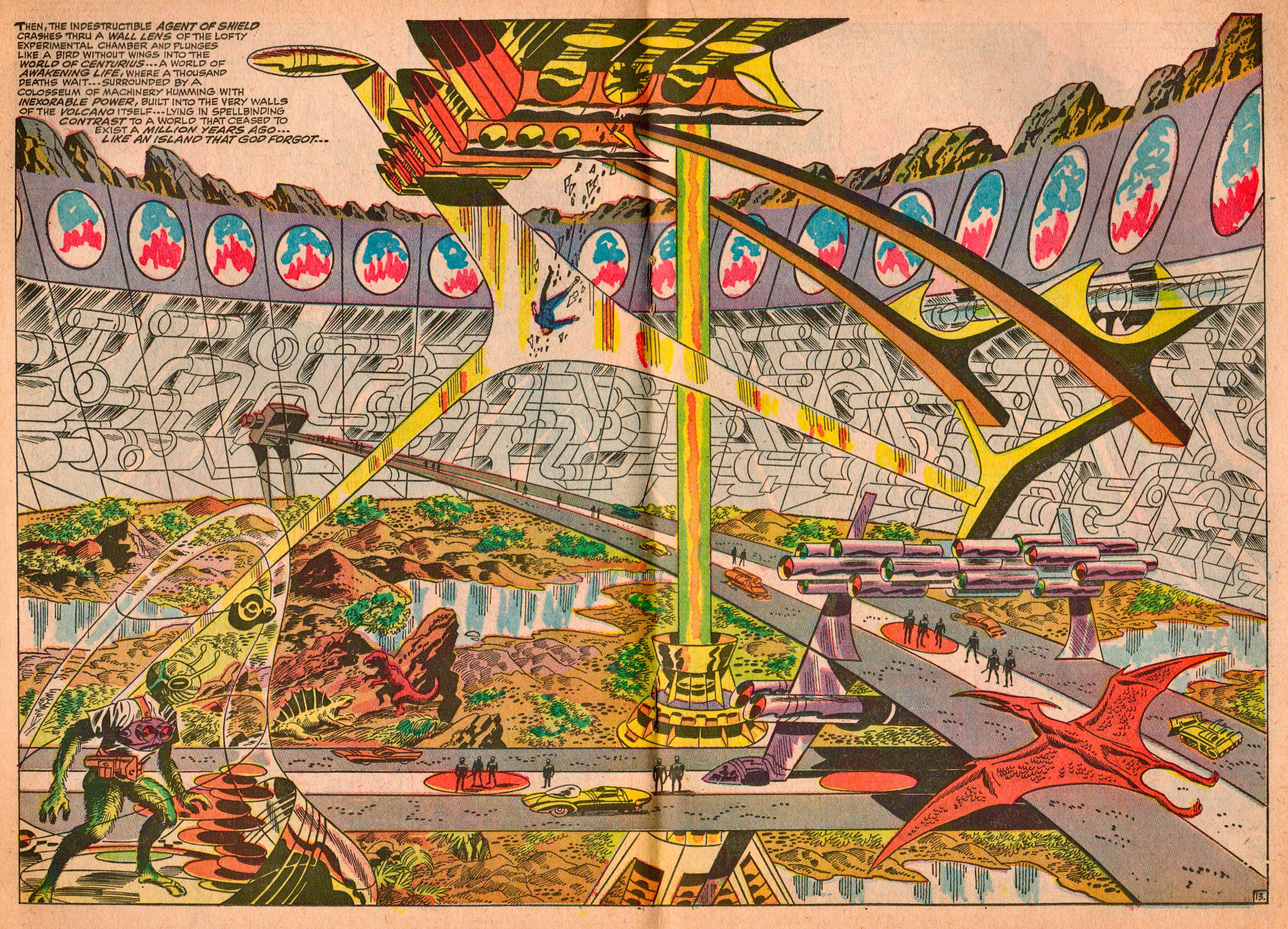

Best single drawing:

This composition never made it into the pantheon of iconic Jim Steranko centerfold images, but let's see if we can't rectify that oversight here, shall we? Ask me, this might be the best image of one of comics' foremost image-makers' career.

How acquired: Back when I used to work at the back issue archive after I dropped out of high school, the Steranko comics stood out like blazing comets that had somehow been stuffed into shortboxes. I used to take them out and stare them over for hours, never reading, only being taken in deeper and deeper by the way they looked. After years of this it finally occurred to me that I could buy them from the place I worked the same way I had thousands of other comics, so then I did. But it's important to me that I dwell on those dusty, dimly lit moments spent in a windowless warehouse poring over the brittle pages of decades-old comics, because that was where I learned to love Steranko's work and, more importantly, to respect it. Like all great comics, it occupies a zone far removed from the sphere of financial transaction, one in which the space between paper and eye vanishes along with petty thoughts of price and ownership. Simply to have looked at those Steranko comics in those moments five or six years ago would have been enough for me. Then and now, the idea that I might possess them for my own seems inconsequential, secondary. It's seeing this stuff that matters. Buying it is neither here nor there.

Suggested soundtrack to this comic: This ...

The history lesson: Jim Steranko, place of prominence in post-Kirby superhero comics, electric visuals that were the only thing in the mainstream able to compete with the late-'60s underground, 32-issue career and out, blah blah blah etc. Steranko's particular genius is pretty obvious from a glance at any drawing from his 1966-70 Marvel Comics heyday. And heaven knows his is a story that's been told enough times, most often by the man himself. Nah, what I want to talk about is Steranko's style. While he was a visionary colorist who contributed as much as anyone else to comics' library of visual effects, as well as a fantastic layout artist and a highly underrated draftsman, what makes Steranko truly unique is what everybody attempting to copy him has missed. In 1968, there were very, very few writer-artists working in superhero comics, and the one who gave the pictures he drew the greatest amount of privilege over the story they were telling. In a visual medium, the logic of this approach should be patently obvious, but in superhero comics, whose primary focus for decades has been the maintenance of "intellectual property" via endless continuing storylines, the importance of the picture here and now is usually passed over without a backward glance.

Steranko, though, made superhero comics the right way, ones in which the stories about big strong bossmen wrestling stood comfortably revealed as the sophomoric trash they were and would remain, and in which every single panel carried an explosive charge of pure energy, because who cares about moving such stupid plots along at an even pace anyway? The second issue of Steranko's tenure on Nick Fury's solo series is the pinnacle of his frenetic "Zap Art" style, twenty pages so extravagantly overloaded with groaner plot wrinkles and savagely inventive ideas about picture making and the comics form that it's easy to spend an hour or more just making your way through. It's just as easy to see why Steranko's influence, so prominent in American action comics until the second half of the 1980s, went on the wane in a post-Watchmen, post-Dark Knight Returns world: It's the antithesis of the incremental, structuralist novels that it hadn't previously been entirely clear superhero comics could pull off. In the years since then, superhero comics' shift away from reliably delivering a satisfying payoff in every panel to very occasionally delivering a really satisfying payoff at the end of a few hundred pages has mirrored its art's move away from Steranko's bold, free stylistic gestures. The reason "Steranko" codes today for little more than low-voltage attempts at retro psychedelia is because he created an entire language in his time, one that's been roundly rejected by the present.

To stretch a metaphor, S.H.I.E.L.D. #2 is the Rosetta Stone ...

Why it's the greatest comic of all time: As with any Steranko comic, the drawing is a huge part of it -- the biggest, probably. Figure after figure, background after background, panel after panel, page after page, no quarter is given here: everything set down on the page is set down with an almost frightening drive, the clear intention that this one is going to be the best picture in the comic, at least until it comes time to draw the next. One of the more unusual things about Steranko is that for a cartoonist with a profile as high as his, he never really managed (or simply wasn't in comics long enough) to fully assemble a style of his own -- the heavy Kirby riffing of early Steranko gives way to Gil Kane and Carmine Infantino nods in his middle period before fading into a fascination with the photorealistic comics art of Alex Raymond and Frank Frazetta toward the tail end of his Marvel career. Perhaps this is another reason why "Steranko" today is widely perceived to be little more than a kit of cheap op-art effects: there's nothing else to function as a signature, no single type of line or shape or feathering around the eyes to stand out as a telegraphing code for the man's style. S.H.I.E.L.D. #2 sees Steranko's art momentarily occupying a place of relative balance, a basic Kirby-derived style with heavy doses of Wally Wood slickness and Peter Max psychedelic overload ground into it.

There's a good amount of pleasure to be gotten from looking at a Steranko comic that just looks like Steranko, seeing a master cartoonist pause somewhere comfortable for a few pages before stretching out once more. More than this, though, the slight self-consistency displayed in Steranko's drafting becomes absolutely necessary in the face of how completely pedal-to-metal overdone everything else is. This is noise comics long before Gary Panter: Steranko was never more willing to follow his graphic ideas to a fever pitch than he is in this issue. The steadiness of the artwork is quite simply the only thing one can hold onto once the covers of this issue are cracked: S.H.I.E.L.D. #2 resembles several separate comics thrown together into one pamphlet as much as any kind of continuous narrative.

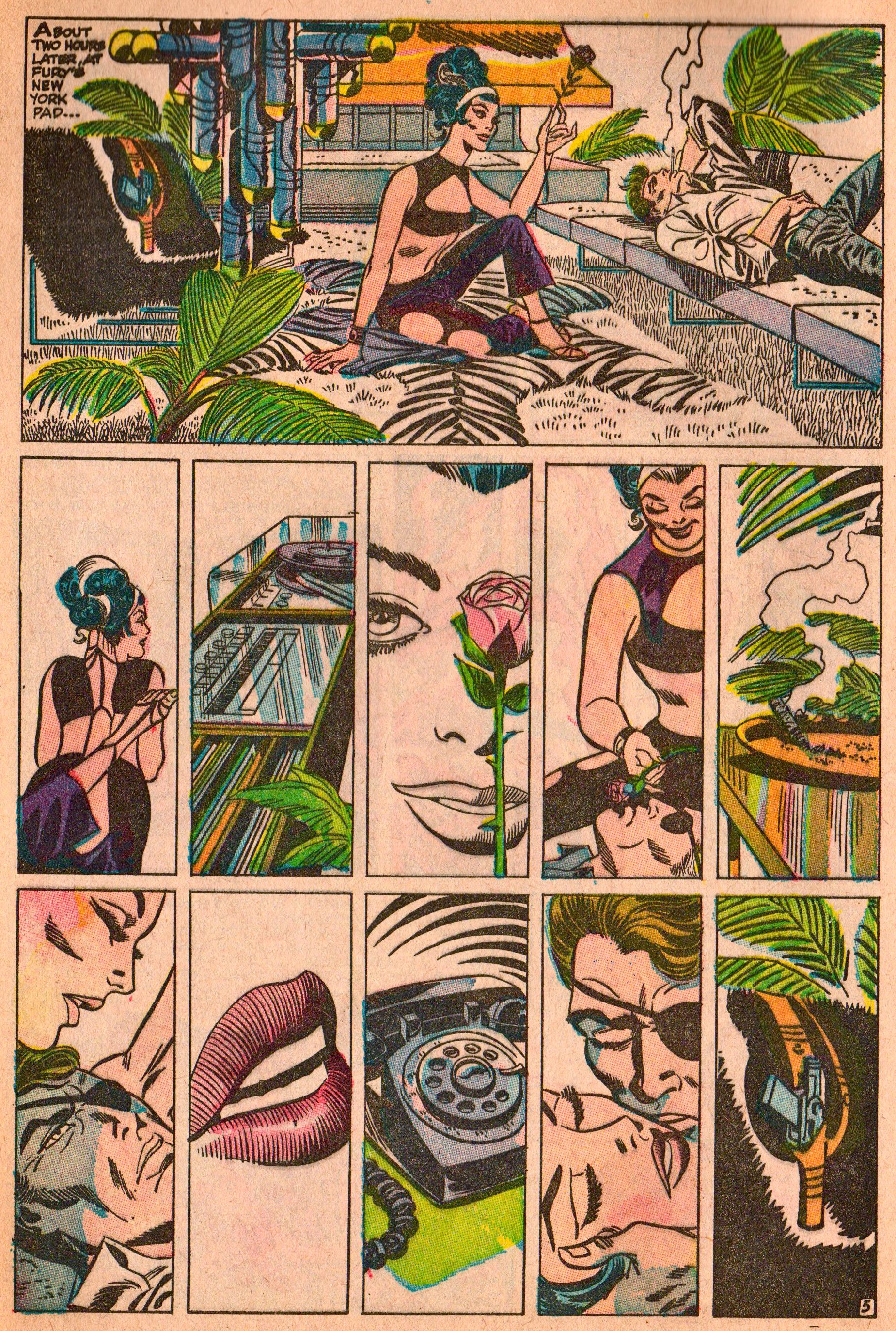

FUN HOUSE, reads the bold lettering on the opening splash page, bigger than the creator's name, the story's title, or even the opening picture of the main character. And if any comic ever lived up to the billing, this is it. It's a spy comic, opening with a sequence of Nick Fury's right hand man Jimmy Woo breaking into a funfair fortress guarded by living skeletons and using all the skills at his disposal to survive (the place is "like a huge puzzle... but not impossible for the Eastern mind to easily grasp!" one of Woo's thought balloons tells us; that's right, folks, one of Jimmy Woo's superpowers is being Asian). It's a romance comic, breaking from Woo's narrative into a single page featuring a moment of solitude between Fury and his girlfriend Valentina (hello, Guido Crepax) that's breathtakingly elegant and sensual even by today's standards -- and judging from the reactions to this comic seen in the letters page a few issues later, severely blew a few old-school Marvelites' sweet little minds. Just look at it, Jesus Christ:

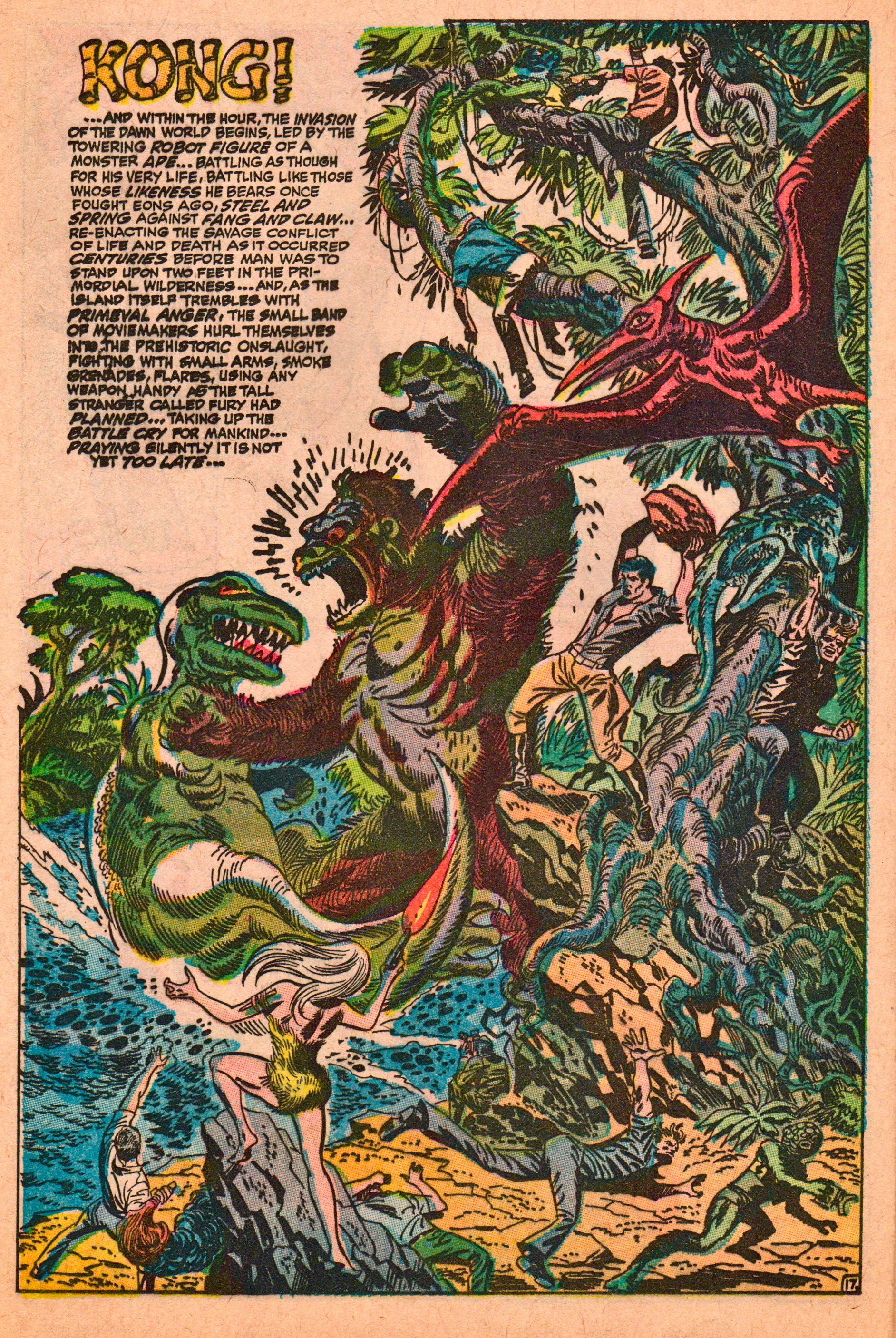

But after the most sublime moment superhero comics had ever managed in 1968, it's back to the action. We're just getting started: it's a superhero comic, as Fury pivots without warning from the embrace of a hot girl to that of a giant butterfly, which carries him to the technofied island lair of Centurius, a kind of latter-day Dr. Moreau, and also the first-ever African American supervillain, thankyouverymuch. It's a sci-fi comic, with the evolution of all life of Earth recapped in four panels before a fifth brings us into the future with a terrifying doomsday scenario. And it's an old-school jungle action comic, as, I swear to God, King Kong and dinosaurs end up saving the day when the efforts of our heroes prove futile. Of course, it's an underground comic and it's an experimental comic throughout as well, with Steranko's vacuum-packed psychedelic spreads matching any of the West Coast's Zap Comix crew for sheer immensity of vision (occasionally presaging the great Rob Liefeld in their overwhelming lust for filling space with line), his layouts constantly moving from one previously unseen form to the next, chopping tiers of panels to ribbons before breaking free with full-page vistas of destruction. There isn't really a succinct way to adequately describe S.H.I.E.L.D. #2 -- rather than sum it up, one can only look at its pictures and catalog its vast array of different parts. In the end, as with every Steranko comic, those parts don't add up to a whole greater than their sum, but it's impossible not to be taken in by the sheer creative energy powering a cartoonist willing to try so much, and at such a dizzying pace. Whole careers in comics have showed less range than Steranko does in these 20 pages.

And in the end, maybe that's the real reason for the brevity of Steranko's career in the comics, the failure of his work to make its mark in some other art form, the lack of the true second act he's been promising the medium for over 40 years now. Comics just can't do enough things at the same time for the pace and heat that Jim Steranko's imagination boiled forward at, and if that's the case, what chance do painting or set design or pulp prose have? Steranko's attempts at all those media were total non-starters, but in sequential art he found a momentary repository for his energies. It was never going to last forever. But nothing truly fascinating does.