The greatest comics of all time don’t appear on bestseller charts or canon lists or big-box bookstore shelves. They are the property of the back issue bins and thrift store crates and convention hawkers of America, living like the medium itself in the unseen crags and pockets of publishing history…

Daredevil #220, composed and drawn by David Mazzucchelli, colored by Christie Scheele, scripted by Denny O'Neil, with unspecified assistance by Frank Miller. Cover-dated July 1985. Published by Marvel Comics Group.

How acquired: In a back-issue sale at the worst/best comic book shop in the Los Angeles area. You know the type of place: dust everywhere, smell of Indian food, way too hot, full boxes of X-Force #1 from the early '90s blocking the shelves in the back. The type of place where when they have a half-off bin blowout you can grab all the David Mazzucchelli Daredevil issues for a flat fee, and get them to let the ones that aren't in the bins (like this one) go for half price too, provided you're willing to sell them your heavily dented copy of Absolute Watchmen.

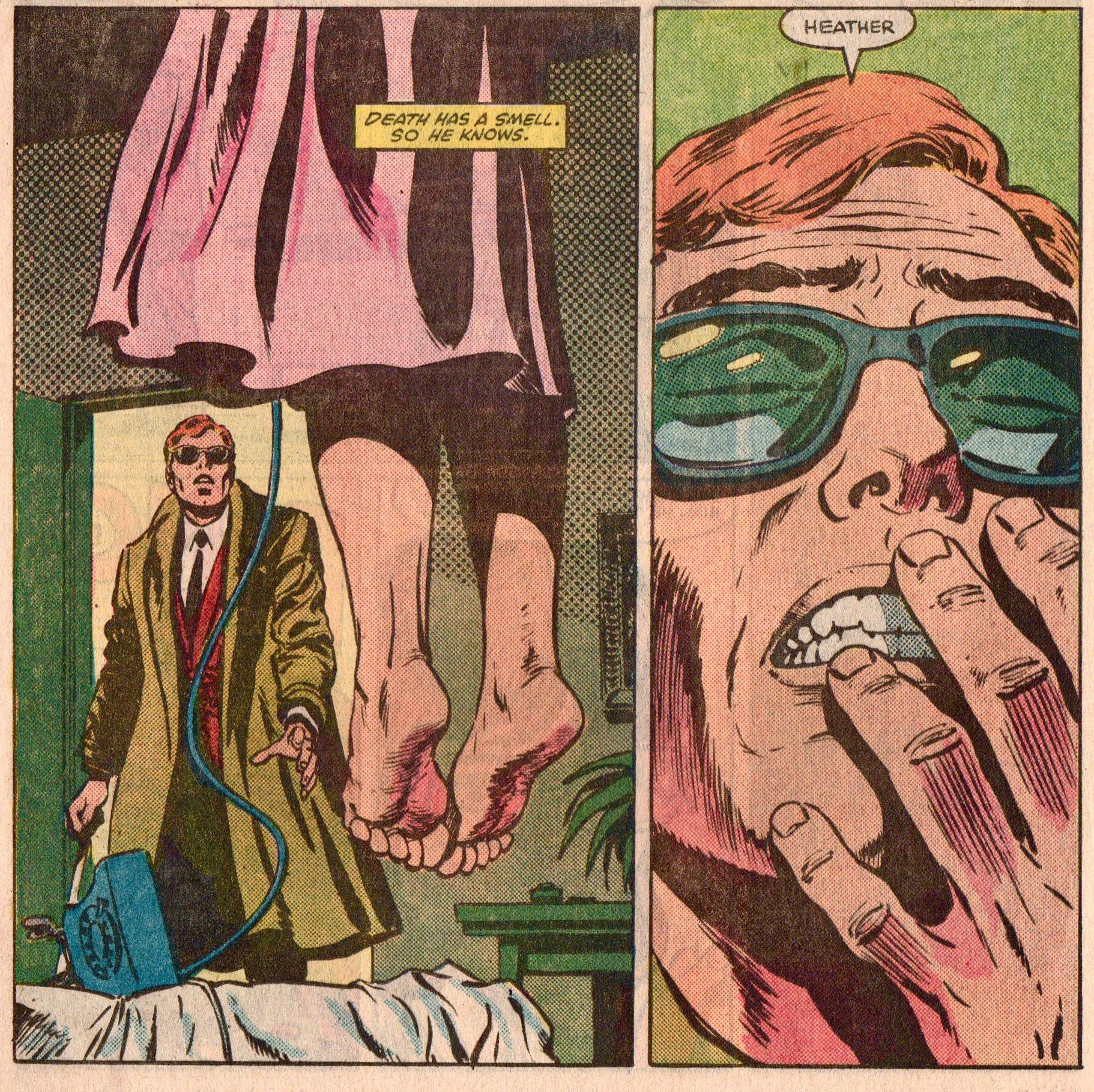

Best single drawing:

No holding lines, no problem. Christie Scheele's two-tone coloring is also aces. But what's most exciting is seeing this much care and virtuosic skill lavished on a panel of a superhero comic that doesn't feature any superheroes, or even any main characters at all. Attention to detail's a real benefit when it looks more like this and less like crosshatching every last hair of stubble on the hero's jawline.

The history lesson: In 1985 superhero comics were standing around in an ever-burgeoning state of excitement as the first frothy waves of a sea change nipped around the genre's ankles. All the prime movers of the mid-late 1980s hero renaissance had come onto the scene, and the comics only got better and more audacious: from Frank Miller's early run on Daredevil to Alan Moore's barnstorming Swamp Thing to Howard Chaykin's masterpiece American Flagg! to Peter Milligan and Brendan McCarthy's visionary Paradax! (the vogue was clearly for titles that featured exclamation points). Things eventually came to a dizzying, still-unequaled climax with the one-two punch of Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen and Miller's Dark Knight Returns, but it's important to note how the superheroes got to those landmark titles from the lesser-known hints at them mentioned above. All the early '80s' fascinating stabs at a more mature superhero-comics acme had one thing in common: they retained some sense of the whimsy and fantasia of the high Silver Age work that had inspired their creators as children. What made Dark Knight and Watchmen such fascinating departures was their total rejection of innocence and light for a highly pessimistic realism.

Those two books, though, were only tapping into a wider zeitgeist. Regardless of the genre's two great masterpieces' sensitivity to the times, bad vibes were coming to superhero comics no matter what. Daredevil #220, seemingly just another issue of one of Marvel Comics' more accomplished titles, was the first chink in the armor, courtesy of veteran writer Denny O'Neil (himself a survivor of the genre's lightest days) and immensely talented young artist David Mazzucchelli (who would go on to create probably the third and fourth best comics to come out of the dark-wave superhero '80s in collaboration with Miller -- Batman Year One and Daredevil Born Again -- before leaving superheroes altogether for the greener pastures of alternative comics). The presence of Miller himself in the book's credits is a bit of a question mark: what exactly he did is unclear, but the issue's plot developments clear the table for Born Again, and the issue betrays both Miller's heavy Will Eisner influence and the more downbeat tone he more than anyone else was responsible for introducing to hero comics. This is where the superheroes went dark. This is where the modern era of America's favorite pulp storytelling genre well and truly begins.

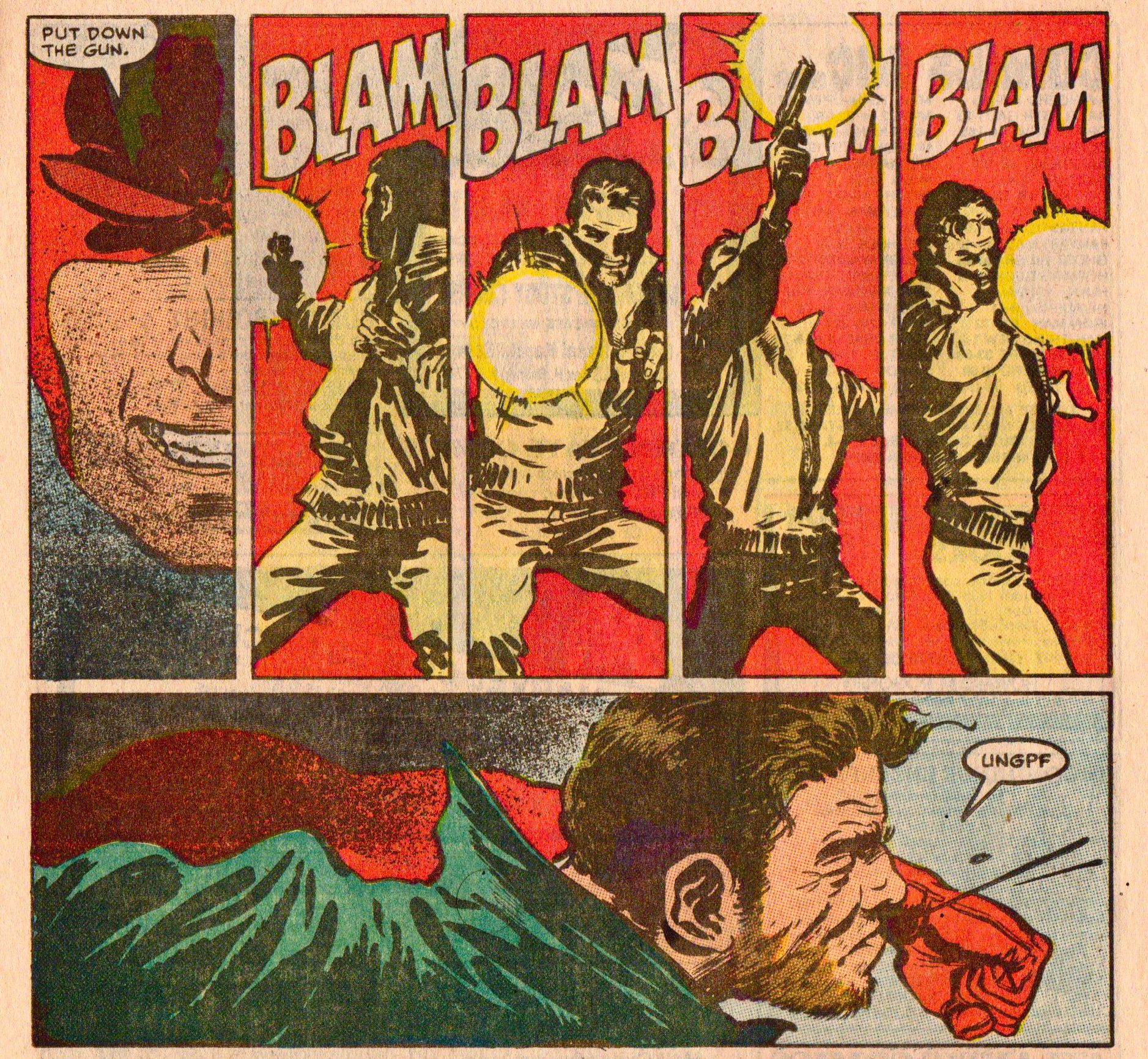

Why it's the greatest comic of all time: Historical importance aside, this is just a fantastically put-together comic book, a great example of how work done in the assembly line process of work-for-hire comics can occasionally become more than the sum of its parts. The big draw is Mazzucchelli's art, about which the editor of a major superhero website remarked "I can't believe this is in a Marvel comic" when I showed it to him. Indeed. What makes the best of Mazzucchelli's pre-alt-comics work so special is how convincingly he was able to pull off the meat and potatoes of superhero action without ever resorting to the lexicon of stock poses, angles, and compositions laid down by Jack Kirby and company in the mid-20th century. Instead, Mazzucchelli's best pre-Born Again work looks something like action comics by an artist who combines the best of Bernard Krigstein, Raymond Pettibon and Edward Hopper. The slashing, immensely bold brushwork gives straightforward shots of hands and faces the visual might of a great punching panel, and when the punches do start flying his emphasis on figure drawing and realist gesture sells the bones they jar and the blood they draw much better than the kind of amplified blocking this comic makes a point of avoiding would. The approach to violence on display in this issue's panels is almost a matter-of-fact one, far removed indeed from the balletic fury most comics about fighting strive for. Mazzucchelli saves the high drama for ink-splattered panels of ran falling, buildings jutting into clouded skies, fog turning a city into a collection of grainy gray rectangles.

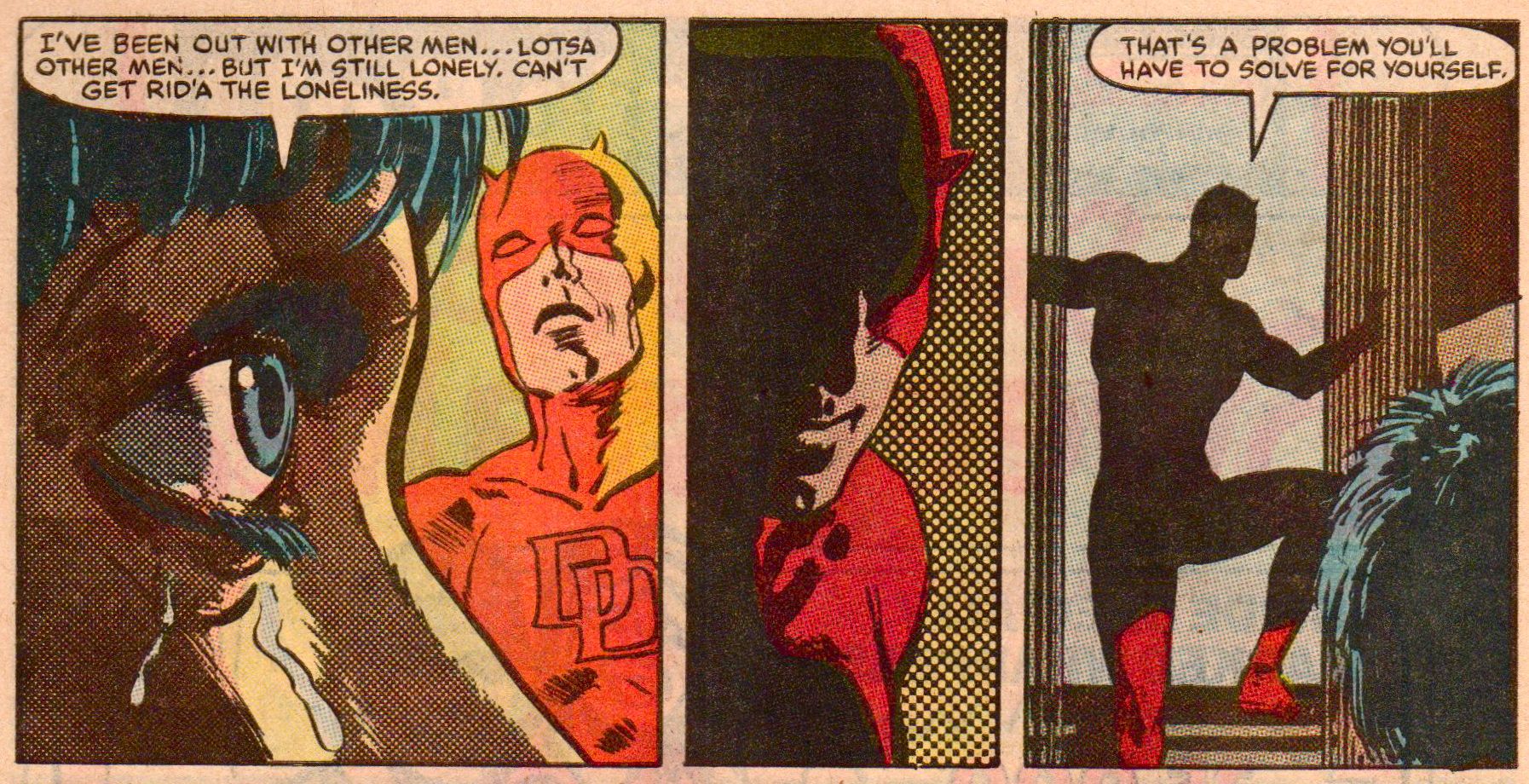

It's an atmospheric, deeply dramatic approach to comics art, and yet one that never sacrifices its sense of realism for a big moment. In this, Mazzucchelli is perfectly simpatico with O'Neil and Miller's story, which is one of the most unremittingly downbeat things superhero comics -- even now, but especially in 1985 -- have played host to. Had an artist other than Mazzuchelli drawn this comic it wouldn't be the tour de force it is, but the content would still shock. The basic purpose Daredevil #220 serves for the book's pre-Born Again master plot is getting rid of the hero's wealthy, unstable ex-girlfriend Heather Glenn, who it's obvious neither O'Neil nor Miller have much patience for. Rather than create a long-running romantic saga, this issue goes quick and clean: a page and five panels of Heather drunk and dissolute, followed a bit later by her suicide. In itself this isn't so shocking (though judging from the letters pages of subsequent issues, it was at the time of publication) -- but seeing it depicted in Mazzucchelli's completely unsentimental old-school comic book style is still highly unnerving.

Over the issue's second half, it appears that O'Neil and Miller have hedged their bets, with Daredevil swinging around town convinced that his former flame was the victim of foul play rather than her own depression. It's easy to be fooled: this is still a superhero comic, after all, and the hero bringing his girl's killers to justice is always going to play better, to be more narratively satisfying in that context than anything else. We get what we came for by the closing pages -- the gangster who burgled Heather's apartment on the night of her death in police custody, the mystery of the stray cigarette butts beneath her hanging corpse solved. And yet it all feels a little hollow, the catharsis of seeing a white-suited and mustachioed mafiosi beaten and humiliated unable to match the impact of Mazzucchelli's knife-in-the-gut reveal of the damsel in distress's lifeless body. Then, as the villain confesses, the reversal: she was already dead when the robbers got there. Which makes the basic point of this comic that it isn't always capital-E Evil's fault. Sometimes desperate drunks just give up and hang themselves. Whether that's a point that a superhero comic should be making is still very much open to question -- as it will be until the genre musters up something that surpasses the aesthetic mastery of its cold and bitter '80s magnum opuses. But when it's delivered in a comic this artistically brilliant and certain of itself, it'll always be worth reading.

Cover price: 65 cents, and you can probably still find it for around that much if you're willing to dig a little.